- Thursday, 12 March 2026

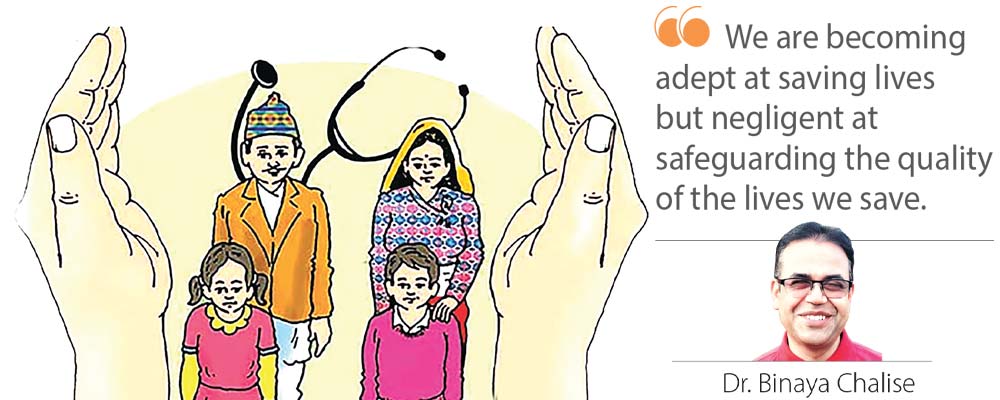

Healthy Years Are Nation’s Wealth

Meet Sita—a 38-year-old schoolteacher in Kathmandu and a mother of two. Last year, she survived a severe bout of dengue. The official headlines counted her as a success story. But survival did not mean a return to normal life. Months later, a motorbike accident left her with chronic joint pain.

She still teaches, but standing is a struggle, and exhaustion follows her home. Her students see it, her family feels it, and the nation’s productivity quietly bleeds as a result. Sita’s story is not exceptional; it is Nepal’s everyday reality. As a nation, we have become adept at counting deaths.

We report outbreaks, tally fatalities, and celebrate survival. What we rarely count are the years lived in pain, the learning disrupted, the productivity lost, and the potential quietly diminished. Millions of such years vanish each year—not with drama, but in silence. This invisible loss is Nepal’s true health crisis. Until we measure what it actually costs to live with illness and disability, we will keep treating symptoms while the nation’s future slowly erodes.

Accounting for health

Our health policies are shaped by what we choose to count. Today, that scorecard is dominated by mortality—how many lives were lost, how many beds were filled, and how many emergencies were managed. Death is visible, dramatic, and politically compelling.

But as a measure of national health, it is a catastrophic blind spot. Imagine a corporation that gauges success solely by avoiding bankruptcy. It would ignore declining productivity, worker burnout, and failing machinery—right up until collapse. This is precisely how we judge health.

By fixating on life and death, we remain blind to the vast middle ground where millions of Nepalis now live longer but in poorer health. Such a scorecard produces predictable responses.

When deaths rise, we build intensive care units. When outbreaks occur, we mobilise emergency responses. These actions are vital—but they are fundamentally reactive, fighting fires already raging. Meanwhile, chronic pain, mental health conditions, injuries, and long-term complications quietly accumulate. They rarely make headlines, yet they steadily erode learning, earning, and economic participation.

A system that counts only deaths will forever treat health as a crisis to be managed, never as the foundational capital of the nation to be nurtured. When we measure health poorly, we invest poorly.

A scorecard obsessed with mortality inevitably pushes public resources towards visible, late-stage interventions—expanding hospitals and emergency responses—while the quieter drivers of long-term loss are pushed into budgetary shadows.

The cost is a systematic misallocation of our future. Conditions that rarely kill but steadily disable—mental health disorders, chronic pain, and long-term injuries—receive a fraction of the attention they deserve. We are trapped fighting yesterday’s battles. As deaths decline, Nepal’s burden has shifted towards chronic conditions and injuries. Yet policy remains locked into an outdated picture of what “ill health” looks like. We are becoming adept at saving lives but negligent at safeguarding the quality of the lives we save.

This is a profound governance failure. Each year of healthy life lost to preventable disability means a student falling behind, a worker’s productivity stalled, and a family’s resilience weakened.

These losses compound in silence, eroding the very human capital our development plans presume. You cannot manage what you do not measure. When we fail to measure the full burden of disease, we end up budgeting—quietly and repeatedly—for a poorer future. What Nepal needs is not just more data but a smarter ledger.

We must account for health not in lives saved or lost, but in years of human potential preserved or squandered. This is precisely what the Burden of Disease framework provides. At its core, it asks a simple question: how many healthy years does Nepal lose each year, and why? It tracks two distinct kinds of loss. First, Years of Life Lost (YLL)—the tragedy of potential cut short.

The farmer who dies of a stroke at 50 instead of 80, or the young mother lost to childbirth. These are years gone too soon. Second, Years Lived with Disability (YLD)—the slow drain of potential. The student was paralysed by anxiety.

The grandparent who can no longer walk to the market. These are years lived in the shadow of poor health, diminishing everything from learning to livelihood. Add them together and you get Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs).

One DALY equals one full year of healthy life lost. It is the universal currency of this ledger—allowing a finance minister to compare the cost of a road accident with that of a diabetes epidemic in the same stark unit: lost years of a Nepali citizen’s contribution. Seen this way, the burden of disease is not a technical abstraction. It is Nepal’s human-capital balance sheet—a clear map of where our future is leaking away and where urgent investment can still protect it.

The policy compass

The true power of this health ledger lies not just in how many years are lost, but in how they are lost. The split between years of life lost (YLL) to premature death and years lived with disability (YLD) functions as a strategic policy compass. When lost years are dominated by YLL, the crisis is immediate and fatal. Heart disease and air pollution in Nepal fall squarely in this category.

They claim lives decisively, demanding responses that prioritise prevention, emergency readiness, and rapid care. In these cases, clean air, effective regulation, and strong emergency services save lives outright. When the burden shifts towards YLD, the crisis becomes chronic and silent.

Mental health conditions or nutritional deficiencies, for example, rarely kill quickly, but they hollow out human potential for decades.

An ambulance arrives too late because the problem was never an emergency. These challenges require different levers: strong primary care, social support, and long-term rehabilitation.

Many of today’s most pressing challenges sit uneasily between these extremes. Diabetes and intimate partner violence extract their toll through a mix of death and disability.

This is why the YLL–YLD split matters. It tells policymakers whether to invest in an intensive care unit or a community clinic—whether to send an ambulance or build a ramp. Without this compass, policy drifts. With it, every rupee spent is aligned with the kind of loss Nepal can least afford.

Once health is viewed as a ledger of preserved potential, one conclusion is unavoidable: health is not produced by the Ministry of Health alone. Every sector that shapes how we live, learn, work, and move is, in effect, a health ministry.

For the Finance Minister, the Burden of Disease ledger is not a medical report but an investment guide. Each preventable lost year carries a fiscal cost: foregone productivity, reduced tax revenue, and rising welfare spending. Preventing a year of disability is almost always cheaper than paying for its consequences.

Health spending is not consumption; it is the protection of national assets. For the Education Minister, health is the foundation of learning. A child free from malnutrition or untreated mental distress gains not just years of life but years of effective learning. Classrooms cannot compensate for bodies and minds that are unwell. Reducing disability among children and adolescents may be one of the highest-return education policies available.

For the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure, the links are visceral. Road design dictates injuries and fatalities. Urban planning shapes air quality, physical activity, and chronic disease. Access to clean water and safe public spaces quietly reduces both premature death and lifelong disability. These are not ancillary benefits—they are direct inputs into the national health ledger. These ministries are only examples. The lesson is broader.

Any policy that shapes daily life writes an entry in Nepal’s health ledger. The question for every sector is no longer whether it affects health, but whether it is willing to be accountable for the years of life its decisions either save—or silently squander.

Now, reimagine Sita’s story in a Nepal guided by this health ledger. Her suffering would not be an afterthought. Smarter urban sanitation could have reduced her risk of dengue; safer roads could have prevented her accident. And a strong primary-care system, with rehabilitation and mental-health support, would have ensured that survival did not come at the cost of lifelong pain. In such a Nepal, Sita is not merely “alive”.

She is supported to teach without pain, to contribute fully, and to live with dignity. Multiply her story by millions, and the stakes of our policy choices become unmistakable.

The true goal of development is not simply to add years to life but to add life to years. By measuring every lost year of health, we can begin to reclaim them. Nepal’s prosperity should be measured not only by economic growth but by the full, healthy potential of its people.

(Chalise is an academic researcher specialising in public policy and development economics.)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-original-thumb.jpg)