- Thursday, 12 March 2026

The Border Inside Homes

The time has indeed come for the industry to talk the talk, walk the walk, fasten the seat belt and soar high, keeping in mind that the sky is its limit.

“Do not mention your period in the community.” The warning of what is to come came before I even reached the village. Later, in a community meeting, a woman sitting right next to me, touching me, mentioned how if a menstruating woman touches them, they will start getting sick and the god will get angry. I sat there, the very menstruating woman they were talking about. They were touching me, but nothing happened. They left the meeting smiling and laughing. This realisation sat with me: how strong the hold must be that they would believe this so deeply, even while the ‘danger’ sat right beside them.

At 25, my life has been defined by the chaotic freedom of the capital. My timeline is modern; it is loud, fast, and largely unbound by the old ghosts. But in November, I joined the Local Adaptation to Climate Change (LACC) project, a follow-up to the 16-year Rural Village Water Resources Management Project (RVWRMP), funded by the governments of Nepal, Finland and the European Union. The project is currently working in the Sudurpashchim and Karnali provinces of Nepal, and through my work here, I travelled to the Sudurpashchim province for the first time last November.

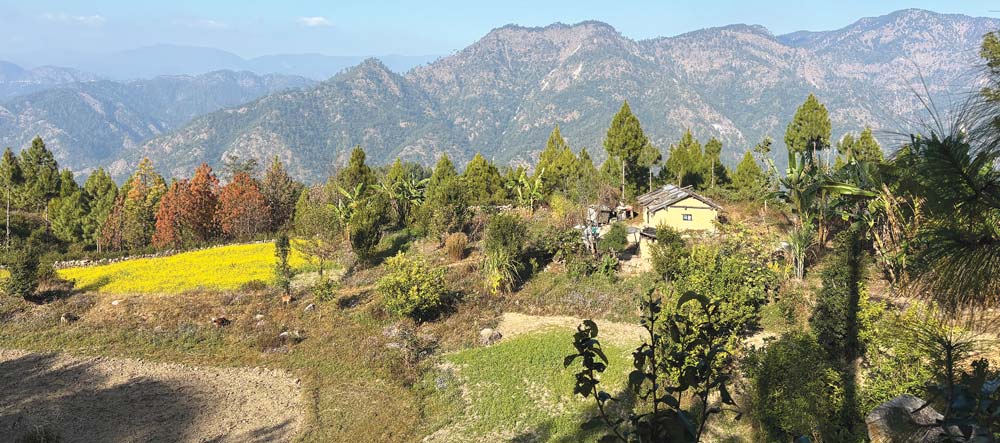

The villages here are beautiful. If you stand on the ridge looking down, the land seems peaceful, the kind of stillness we pay to find. But if you listen closely to the women who live here, you realise that the silence is not just peace.

In one timeline, the official one, Nepal is a modern republic. The supreme court had directed the government to end the practice of Chhaupadi, an ancient Hindu practice that banishes women from home during menstruation and after childbirth, in 2005. Chhaupadi was criminalised in Nepal by the Criminal Code Act of 2017. The law stipulates a three-month jail sentence, a fine of Rs. 3,000 (about $26 USD), or both, for anyone found guilty of forcing a woman to follow the custom. The Constitution of Nepal ensures the right to equality (Article 18) and explicitly affirms in Article 24 (1) and Article 29 (2) that no one shall be treated with any form of untouchability, discrimination, or exploitation based on custom, tradition, or practices. And yet, just a few steps behind the main house, past the animal shed, you enter a different timeline. Here, it is not 2025. It is a time governed by fear so old it has calcified into law. Pamela remembers when this fear was even more absolute.

Pamela: The long view

When RVWRMP Phase I began in 2006, the team became aware that many taboos that had faded elsewhere were still strictly applied in Sudurpashchim. Changes had come during the civil war, partly due to the efforts of the Maoists to combat caste and gender discrimination and more movement beyond isolated villages, but issues remained – particularly for menstruating women. RVWRMP contracted a Nepali NGO, Samuhik Abhiyan, to conduct a groundbreaking ‘Gender and Social Discrimination Study’ in the field from December 2007 to March 2008, which demonstrated in detail the many difficulties faced by women. From my first visits to the field in RVWRMP Phase II, in 2010, I could see these negative traditions in action, and they were confronting. How could something that is responsible for the birth of all of us be so negative? And how could families risk the lives of newborns, as well as their daughters, by forcing them to stay in a bare Chhau goth (isolation/chhau huts) or be locked into a cattle shed and run the risk of snakebite, wild animal attack or the cold? Some women are even sexually assaulted while isolated – demonstrating that the untouchability taboo applies only when convenient for some men. I even saw cases where Dalit women (who were not traditionally required to comply with menstrual taboos) spent their precious funds to build their own Chhau goth!

There were only a handful of toilets in Far West in 2006, and open defecation was the norm. Therefore, it was only when the work of the project had advanced sufficiently that it became clear that menstruating women were not allowed to use the new toilets because they might make them “dirty”. Villagers became enthusiastic about the messages of the National Sanitation Campaign, building their own toilets and declaring their villages open defecation free by 2016. Yet this ignored the reality that by forcing women to not use toilets during menstruation, it wasn’t in fact ODF, and the negative impacts for the whole village would continue – let alone the discomfort and risks for those women and the sense that there was something wrong with them.

The taboos reach into many parts of women’s lives. Even after women were elected to local government in 2018, representation couldn’t be assured, as many felt they couldn’t participate in meetings if menstruating. Female teachers and students couldn’t attend school during menstruation, particularly if there was a shrine on the premises. And pregnant women in labour couldn’t reach the clinic if they had to pass a shrine on the roadside.

We have tried many ways to change behaviours around these taboos. The first target audience is women themselves. Everyone knows your business in a village, and it is difficult for a woman to break the ‘rules’ when they are menstruating. If, for instance, they drink milk or touch the tap while menstruating, and a cow or a family member gets sick, they blame themselves. No amount of reassurance by me, a veterinarian, that cows didn’t get sick as a result of my own menstrual status, would convince them! Even some women who were initially influenced by our campaigning pulled down their chhau hut and stayed inside their house and would sometimes have misgivings and sleep outside again (sometimes in the open!).

Key persons to convince are the older generation (including mothers-in-law who felt that if they had to go through it, then their daughter-in-law should too) and traditional religious leaders. Younger men usually weren’t concerned, but as they often left the village for seasonal work, their wives were left at the mercy of their parents. RVWRMP tried many ways to change hearts and minds. These included participatory video, Dignified Menstruation Management (DMM) workshops, work with religious leaders and child clubs, webinars, community theatre, sasu-buhari workshops, sanitary napkin training, and perhaps most successfully, celebrity singing ambassadors (such as Rekha Joshi). Our aim has been to ensure everyone in the community is comfortable speaking about menstruation, just as we learnt to talk about ODF without shame. Many locals are searching for ways to tackle taboos, reflecting the human rights conventions signed by Nepal and the new Nepali Constitution and its roll-out to the local government level.

In 2022, we revisited many of the communities visited by the research team in 2007 and discussed some of the same topics. It was impressive to see how far many of the communities had come. Women have worked hard and are taking leadership roles, overcoming many of the barriers they faced. In most households, women can now sleep inside their own home, albeit sometimes in a separate bed, and can use the toilet, though usually with a separate water pot, and sometimes employing cow’s urine to sprinkle over the area to ‘purify it’.

Now returning in 2025 to Sudurpashchim with LACC, with our new staffer Aarzoo, it was interesting to see things through her eyes. To me, things have improved enormously for women since my first visit in 2010. But pockets of Chhaupadi taboos remain (even in households that don’t practise it when living outside of their village!). I had hoped that we wouldn’t need such a focus on this topic in LACC, but it seems that there is still a lot of work to do.

Aarzoo: The reality of 2025

Pamela had seen the landscape change over decades, yet she warned me about the persistent fear that still grips these communities. Despite her preparation, the reality of that fear did not truly hit me until I stood before a group of students and asked a single, heavy question that should not carry such weight in 2025: “Who here still stays in the Chhaupadi hut?”

In the back, a few hands went up. They were unsure, timid. I could not stop looking at one of them, a 15-year-old young girl. She walks three hours every day to get to school and back. When I asked her what it was like in the shed, she did not speak. She did not have to. Her eyes just filled with tears.

She looked so familiar. I had never met her before, but as we looked at each other, I realised I was seeing a ghost of the future I hoped she would have. I saw her sitting at a desk in a corporate office, confident, working, laughing. I was glimpsing the woman she should be, staring back at the frightened girl she is forced to be.

Whether in the village or the classrooms, the logic is the same. The Chhaupadi hut is not just a building; it is a border. On one side is the home, warm, safe, and pure. On the other is the wilderness, cold, dangerous, and impure. “We are barred from the toilets. We cannot touch the water taps,” the women in Sera village in Chure Rural Municipality told me.

Think about the violence of that sentence. Nepal is a nation that was declared Open Defecation Free (ODF) in 2019, where every ward proudly states that every house has a toilet. In a village celebrated for its hygiene status, women are forced to walk fifteen minutes to the Thuligad river to wash. They look at the taps in their own yards, water that is safe, clean, and right there, and they walk away. They walk past the toilets built for their safety and out into the open fields. Why? Because the water is more sacred than the woman.

When I asked a man in Sera why they would not just bring the women inside, arguing that the laws and police were on their side, his answer took me aback. “If we bring them inside,” the man told me, “you will have to take responsibility for our gods.”

In their eyes, the safety of the divine rests on the shoulders of a menstruating teenage girl. If she touches the tap, the god is thirsty. If she touches the cow, the milk dries up. The community has convinced itself that their gods are so fragile that a natural biological process can shatter them.

This belief is not just an old superstition; it is active today. At the school in Chure, students told me about a ‘disease’ that had swept through the classrooms. This ‘disease’, likely a mass psychogenic illness caused by collective anxiety, serves as a physical manifestation of the stigma that haunts these classrooms. When fingers are pointed at a menstruating girl, it is a reaction rooted in fear rather than biology. It reminds me of a line from Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns: ‘Like a compass needle that points north, a man’s accusing finger always finds a woman. It is exactly this cycle of anxiety that our Dignified Menstruation Management (DMM) workshops aim to break, replacing ancient fears with the confidence of education.

There is a myth in these hills that the women are used to it, that they are strong. A man in the village told me casually, “Nothing will happen. Nothing ever happens.” He is wrong. We know exactly what happens.

The news reports from 2025 alone reflect the irony in his statement. In August, a mother and her 7-year-old daughter were crushed to death by falling stones in an Achham hut. In July, a 28-year-old mother died of a snakebite in Kanchanpur, just metres from her concrete home. In January, a woman was mauled by a tiger in Kailali. To claim ‘nothing happens’ is to ignore the bodies of the women who did not survive the night.

We often talk about smashing the sheds; we tear down the mud structures. But in Sera, and in the tearful eyes of that student in Chure, I saw that the real prison is built inside the mind. To dismantle these walls, the LACC Project applies GEDSI and human rights-based approaches to every tap we install and every garden we plant. We are not just building infrastructure; we are working on building the confidence every girl needs to believe that she has the right to touch the tap, no matter what time of the month it is.

A woman’s dignity is not the price of a family’s salvation. Until every woman in Sera can use the toilet in her own home without fear, Nepal’s Open Defecation Free status remains a hollow claim. We must look past the official certificates and see the girls still walking to the river in the dark. Until that 15-year-old girl in Chure can sleep in her own bed without fearing she has angered a god, she is not free.

The years pass: 2006, 2018, 2025. The laws change. But in these hills, the shed remains. And it is time, long past time, to bring the girls back home in all villages and keep them there.

(White is an International expert and Nepal is a communication officer of the Local Adaptation to Climate Change (LACC) Project.)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-original-thumb.jpg)