- Friday, 6 March 2026

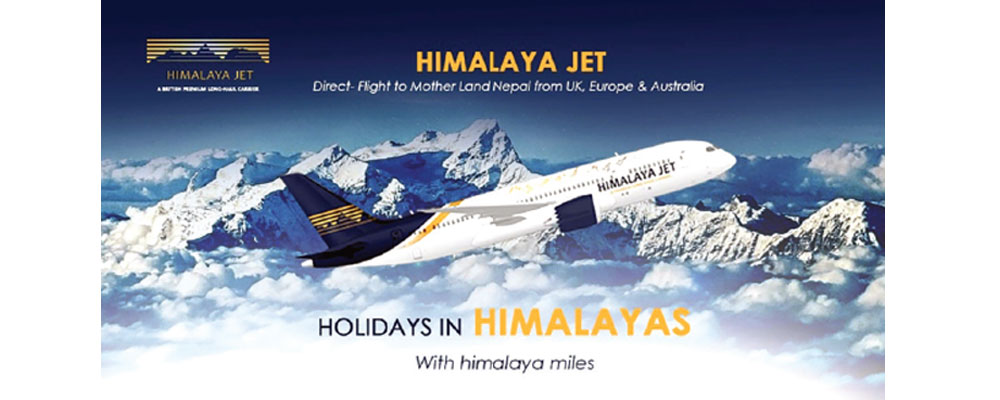

Bringing Himalayas Closer To World

Himalaya Jet has positioned itself as a rare kind of startup: a UK-based, premium long-haul carrier built explicitly around Nepal and the wider Himalayan region. Incorporated in the United Kingdom and headquartered in London’s Mayfair, the airline markets itself as a “premium long-haul” operator and has publicly stated ambitions to link Europe, the Middle East, North America and Australia directly with Kathmandu and other South Asian destinations over time. At the centre of the project is British-Nepali investor Dipendra Gurung MIoD, whose family office has interests in real estate, hydropower, luxury hospitality and entertainment, including a stake in the Miss World franchise.

Gurung is presented as both founder and principal shareholder, and the airline has been one of the few start-ups to receive advisory support from Boeing’s Startup programme, following high-profile visits to the manufacturer’s Seattle facilities. On paper, the value proposition is straightforward: instead of connecting through Doha, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Delhi or Istanbul, travellers would board a non-stop Boeing 787-8 between cities such as London, Frankfurt, Paris or Sydney and Nepal. This is aimed squarely at time-poor but relatively yield-tolerant passengers — a mix of Nepali diaspora, tourists and business travellers who currently endure multi-stop itineraries to reach the country. In a market where long-haul links to Nepal have historically been thin and inconsistent, Himalaya Jet is attempting to turn a chronic connectivity gap into a commercially viable network.

Filling a long-standing gap

Despite Nepal’s strong outbound labour flows and growing tourism profile, no EU–Nepal non-stop service exists today. Instead, passengers rely on a patchwork of one-stop options via Gulf hubs, India or Turkey. That pattern reflects both demand characteristics and regulatory constraints. Since 2013, all airlines certified in Nepal have been banned from operating in European airspace under the EU Air Safety List, following concerns over accident rates and shortcomings in regulatory oversight by the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal (CAAN). As of 2025, around 20 Nepali carriers – from major scheduled operators to small helicopter firms – remain barred from the EU market.

Himalaya Jet’s decision to base itself in the UK is therefore strategically significant. A British AOC would place the airline under the UK Civil Aviation Authority’s regulatory framework rather than CAAN’s, meaning it is not subject to the EU’s blanket ban on Nepali-registered airlines. In practice, that gives the carrier a legal pathway to operate into slot-constrained EU hubs that Nepali airlines cannot access, even if its core market is built around Nepal-bound traffic. The underlying demand picture is far from marginal. Recent research estimates that more than 2.1 million Nepalis live abroad, with remittances accounting for roughly a quarter of Nepal’s GDP, one of the highest ratios in the world.

The UK and wider Europe host visible Nepali communities, many linked to the long-standing Gurkha connection, seasonal work and onward migration. At the same time, Nepal’s tourism sector continues to be a key foreign-exchange earner, yet remains highly sensitive to connectivity and perceptions of safety. Direct flights operated under a UK safety regime would therefore sit at the intersection of diaspora demand, tourism strategy and international relations. They could reduce journey times, diversify Nepal’s reliance away from a small group of Gulf carriers, and symbolically tether the country more tightly to European markets at a time when it is carefully balancing relationships with India, China and Western partners. Himalaya Jet’s narrative of “patriotic” flights to the “motherland” is framed within that broader economic and geopolitical context.

Fleet choices and slot constraints

From a fleet perspective, Himalaya Jet’s strategy centres on the Boeing 787-8. Public statements and reporting suggest an initial plan to lease two 787-8s for the first three years, with highly ambitious longer-term talk of scaling up to as many as 18 aircraft if the model proves successful. For a startup targeting long, relatively thin routes from Europe and Australia to Nepal, the type is a rational choice: it offers the range to link Kathmandu with Western Europe and eastern Australia non-stop, while its composite structure and modern engines deliver lower fuel burn and better environmental performance than older widebodies.

However, the 787’s advantages only translate into a sustainable business if the network and economics line up. Long-haul widebody operations are highly sensitive to load factor, yield and aircraft utilisation. Industry experience with airlines such as WOW air and Norwegian’s former long-haul division shows that even modest under-performance in any of these variables can quickly erode margins. For a 787-8 configured with a mixed-class cabin, breakeven often requires sustained load factors in the mid-70s to 80-per cent range, depending on fuel prices and unit costs. Any meaningful seasonality in demand – for instance, strong summer and festival peaks but softer winter travel – increases the risk of sub-optimal utilisation and revenue volatility.

Tribhuvan International Airport introduces another technical layer. The airport sits at roughly 4,390 feet (1,338 m) above sea level, in a bowl-shaped valley surrounded by mountainous terrain. Approaches and departures require careful navigation through narrow corridors, and the single runway 02/20, now extended to about 3,350 metres with a noticeable slope, imposes performance penalties for fully loaded widebodies, particularly on hot days. Historically, concerns over pavement strength even prompted temporary bans on certain widebody operations during periods of runway distress. For a carrier planning non-stop sectors such as London–Kathmandu or Sydney–Kathmandu, this can translate into payload restrictions, especially westbound, with knock-on effects on revenue and cargo carriage.

‘Grandfather rights’

On the European side of the network, airport access may be as constraining as aircraft performance. Heathrow, Paris-Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt are all Level 3 slot-coordinated airports under IATA’s Worldwide Airport Slot Guidelines, meaning declared capacity is fully utilised and access is tightly controlled. Incumbent carriers benefit from “grandfather rights” over historical slots, subject to the familiar 80/20 “use-it-or-lose-it” rule. For a new entrant without an established portfolio, obtaining peak-time slots typically requires either purchasing or leasing them from another airline, accepting marginal times, or shifting to secondary airports such as London Gatwick, Stansted, Luton or Paris Orly.

If Himalaya Jet is forced into secondary airports or off-peak departures, the consequences cascade through the business case: weaker schedule competitiveness, reduced appeal for time-sensitive passengers, and potentially lower aircraft utilisation if rotations cannot be optimised. Balancing the ideal plan on paper – high-yield non-stops from primary hubs – with the realities of slot allocation, performance limits at Kathmandu and the economics of operating a tiny widebody fleet is likely to be one of the airline’s most immediate tests.

Set against this backdrop, Himalaya Jet’s concept is neither irrational nor trivial. There is clear untapped demand for more direct connectivity between Nepal and Western markets; remittance-driven travel, VFR flows and tourism all point toward a solid underlying market. The use of a modern, fuel-efficient type and a regulatory base in the UK address two of the structural issues that have constrained Nepal-related aviation for years: environmental and cost performance on long-haul routes, and the EU’s continued ban on CAAN-supervised carriers.

However, multiple execution risks remain opaque from the outside. As of late 2025, the airline has yet to launch scheduled services, despite earlier target dates around 2023, suggesting that progress on securing a UK AOC, finalising ACMI or dry-lease arrangements for the 787s, and locking in airport slots has taken longer than initially hoped.

There is also the broader safety and reputational context: recent accidents in Nepal, including a 2024 crash report that renewed scrutiny of procedures and oversight, have kept the country’s aviation record under international examination. Even if Himalaya Jet is regulated from London, it will still be operating into a challenging airfield and wider system that must continuously work to improve safety outcomes.

Key questions remain

Beyond regulation and infrastructure, the project must answer classic questions that have defined the fate of many long-haul startups: Can it secure sufficient capital to absorb early-stage losses? Will the targeted customer base support a premium positioning, or is the market more price-elastic and inclined to remain loyal to established Gulf and Turkish carriers offering dense connecting networks? How will bilateral air service agreements and competition responses shape its route rights and pricing freedom over time?

For now, Himalaya Jet sits in that familiar space between an aspirational business plan and an operational airline. The ingredients – diaspora demand, a modern fleet choice, regulatory arbitrage and a clear market gap – are all visible. Whether they can be assembled into a stable, scalable carrier will depend on decisions being taken largely out of public view: regulatory approvals, financing, capacity discipline and a realistic reading of the competitive landscape. Until those pieces fall into place, Himalaya Jet will remain one of the more intriguing “what-ifs” in the long-haul space, closely watched by both the Nepalese community and industry observers.

(Basnet did his postgraduate studies in Air Transport Management from the University of Surrey, UK.)

-original-thumb.jpg)