- Saturday, 7 March 2026

Cold wave hampers school operation, teaching, learning activities in Madhes

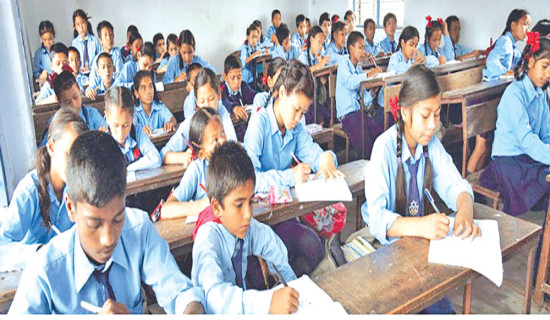

Kathmandu, Jan. 20: Janata Adharbhut School in Aurahi Rural Municipality, Mahottari, was closed for one week at the end of December due to a cold wave. The school had no such schedule to close.

Gyanendra Yadav, headmaster of the school, said that when the cold wave starts it hits students who come from poor families, such as Chamar and Musahar community.

“Students don’t have sweaters or warm clothes. Along with this, the classrooms are under a zinc roof and don’t even have doors and window panels. In this condition, how can we expect them to sit in classrooms for hours?” Yadav told.

The cold has not only affected attendance but also worsened the already high dropout rate in Madhes. Education stakeholders say poverty, seasonal migration, and repeated school closures have made continuous learning almost impossible for many students. Students dislike going to school, and even when they do, they are not

motivated to study properly. Dhan Bahadur Rai, Education Officer of Aurahi Rural Municipality, said the recent holiday was not included in the official academic calendar, but the municipality had no option but to close the schools.

Aurahi Rural Municipality alone operates 20 schools with 6 thousand students, all of which were affected by the closure.

“Despite the learning loss, school closure was unavoidable. Children come to school without shoes and warm clothes. Keeping schools open in such weather would put their health at risk.”

Along with Aurahi Rural Municipality in Mahottari, almost all local governments in Madhes closed schools due to the cold wave. The sudden closure of schools in Madhes in late December was not aligned with the academic calendar.

The severe cold wave sweeping across the Tarai-Madhes region has emerged as yet another major challenge to the already fragile education system in Madhes Province, disrupting academic activities and increasing dropout rates.

Dipak Raj Kalauni, Head of the Education Development and Coordination Unit (EDCU) in Siraha, said local governments exercised their constitutional authority to close schools due to the cold wave. “As education rights are constitutionally ensured to local governments, municipalities have been declaring school closures according to their needs,” Kalauni said.

From the closure, a total of 14,168 students from 762 schools in Mahottari were deprived of study opportunity. The number is large in all eight districts of Madhes Province.

“Schools in the Tarai region are repeatedly disrupted due to heat waves, cold waves, floods, and dengue outbreaks,” Kalauni said. “The frequent disturbance severely affects learning.”

Cold wave linked to climate change

An atmospheric condition is called a cold wave when the temperature (day/night) drops below the threshold temperature for at least three subsequent days.

Thresholds are determined based on the climate (temperature and/or relative humidity) values for the particular region/place. There is no unique technique to determine the thresholds. It differs from country to country. In Nepal, the threshold is based on the daily temperature data of the past 30 years, applying percentile methods.

Indira Kandel, Senior Meteorologist at the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, said that cold waves were not new climate extremes. “The new things related to cold waves are their frequencies and intensities,” she said. “After the 1990s, the frequencies and intensities have been significantly increasing, especially in the Tarai of Nepal, due to which the seasonal temperature trend in Tarai is negative during the winter season.”

Another meteorologist, Saroj Pudasaini, explained that a cold wave is officially declared when the minimum temperature falls by at least 5°C and the maximum temperature by at least 10°C continuously for two days, as measured at two separate temperature measuring centres. The maximum temperature is recorded during the daytime, while the minimum is recorded at night.

He further stated that climate change has caused significant fluctuations in temperature. As a result, the winter season can experience unusually low temperatures, while summers may become unusually hot. Additionally, a low-level high-pressure system can contribute to the occurrence of a cold wave.

Many people mistakenly believe that climate change only causes an increase in temperature. In reality, it increases the frequency of extreme weather events. Therefore, prolonged cold waves may also be linked to climate change.

Nir Bahadur Kunwar, 83, a resident of Bardibas, Mahottari, said that 50 years ago he did not experience the cold wave in the winter. “Sometimes fog used to be seen in the morning, after 10 am it would be sunny,” he said. “I have been feeling cold for the last 30-35 years. Previously, people used to come to Tarai-Madhes from hills to escape the cold.”

Cold waves particularly harm children’s and older people’s health. Dr. Jagat Jeevan Ghimire, pediatric pulmonologist, said that children and the elderly are the most affected during cold waves. He emphasised that avoiding the cold is the best remedy. However, if preventive measures are not taken during childhood, a child may not fully recover even in later years. Speaking about the cold wave in Madhes, Dr. Ghimire added that people there often sit around firewood to keep warm, but the smoke from the fire worsens their health conditions and increases their suffering.

Downsides of Madhes education

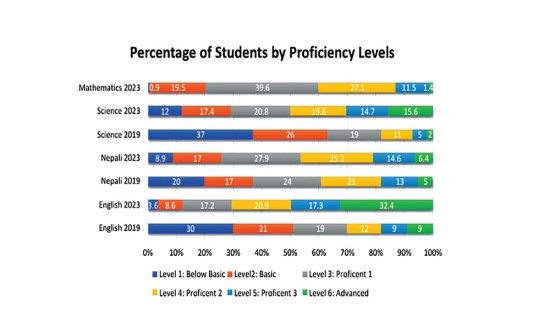

Madhes Province continues to lag behind other provinces in educational performance. This is reflected not only in SEE results but also in literacy indicators. “Out of 77 districts across the country, only eight districts of Madhes Province have yet to be declared literate,” Kalauni said, underscoring the region’s persistent educational challenges.

According to education experts, poverty, social exclusion, climate vulnerability, weak governance, and inconsistent school operation have collectively pushed Madhes behind national averages.

There is a blame that schools often present higher student numbers on paper than in reality, a practice linked to funding and administrative requirements as the federal government allocates funds for day meal and scholarships on the basis of headcount of students.

“The actual number of students attending school is much lower than what is reported,” said a local education stakeholder in Siraha. “This hides the real scale of dropout and learning loss.”

Likewise, the Secondary Education Examination (SEE) pass percentage in Madhes Province remains lower compared to other provinces, reinforcing concerns about the quality of education.

During examinations, the situation often becomes more complex. Even guardians participate in helping students cheat during the exams, which is reported widely in many news media.

Suprabhat Bhandari, President of the Nepal Guardian Federation, emphasised that Madhes Province needs to develop plans to mitigate the challenges posed by extreme weather. He suggested that proper management of air-conditioned rooms and physical infrastructure according to seasonal requirements could be a solution for both cold waves and heat waves.

He noted that schools in the Himalayan region are implementing a concept of mobile school, moving from lowlands to slightly colder areas. He suggested that the Tarai region could also consider this approach as an option. Furthermore, he stressed the importance of ensuring lodging and food arrangements for children in such communities to create a conducive learning environment.

“The cold wave is only a trigger,” said an educationist, Bidyanath Koirala. “The real problem is systemic neglect,” he said and suggested developing another learning module where students can learn even from home through their assignments.