- Tuesday, 3 March 2026

Legal promise, practical gaps: School education neither free nor compulsory

Kathmandu, Oct. 26: Thousands of Nepali youths are set to be disqualified from entering any kind of government services from 2028 if they fail to complete education up to grade eight. The government introduced the Act relating to Compulsory and Free Education, 2075 in 2018 with the aim of ensuring that all citizens have at least qualification of basic education.

The Act was formulated in accordance with the Constitution of Nepal, which guarantees every citizen the right to compulsory and free basic education under fundamental rights. Clause 19 of the Act further states that those who have not completed basic education will be disqualified not only from government services but also from being elected, appointed or nominated to any post in any institution established in the governmental, non-governmental or private sector. They will also be restricted to incorporate any company, firm, cooperative organization or non-governmental organization.

Following the enactment of the law in 2018, individuals within the defined age group were required to acquire basic education.

Aligned with legal provision of constitution and Compulsory and Free Education Act, 2075, there is School Education Sector Plan (SESP) 2022-2032. The SESP reaffirms the obligation to ensure free & compulsory basic education for all children. It also emphasizes cross-sectoral priorities (health, nutrition, protection, etc.) because access to and retention in basic education are influenced by factors beyond school.

According to the SESP, the age for basic education is four to twelve years. Currently, 412,243 children of the age group are out of school, according to the figure of Education Management Information System (EMIS). The number is 15 per cent of total population of this group, which currently stands at 45, 8600.

Though there is some debate over the accuracy of these figures, it is clear that a significant number of children remain outside of school system.

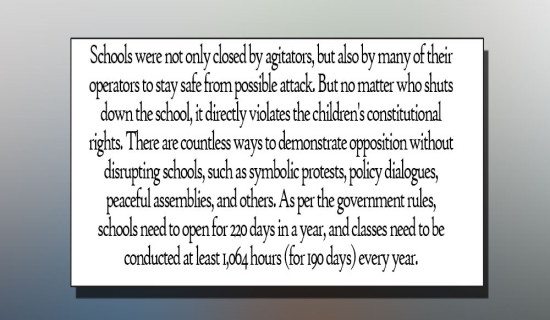

The government has been facing challenges in both enrolling children and ensuring their retention, as dropout rates remain high despite multiple policies and programmes. EMIS data show that 8.2 per cent students drop out between grades one and five, 5.4 per cent between grades six and eight, and 4.7 per cent between grades nine and ten.

To improve school attendance, the government has implemented several measures—such as teacher management reforms, free textbook distribution, mid-day meal programmes, scholarships, and the provision of sanitary pads. However, most of these are general programmes, and there are few targeted interventions for children requiring special attention.

Shankar Adhikari, under-secretary at Planning Division of the Ministry of Education Science and Technology (MoEST) indicates the budgetary insufficiently as major challenges to mitigate the problem. He further said, “There is ongoing conflict among the three tiers of government. Each level seeks to exercise its own authority while expecting others to fulfill their responsibilities. The same situation is evident in the education sector, even though it is recognized as a common right in the constitution,” Adhikari said.

According to Adhikari, the government has been facing trouble to enroll all students mostly from Karnali and Lumbini. Lack of parental awareness, poverty, school distance and household responsibilities contribute to low enrollment and high dropout rates.

Besides these children, large number of students having multiple disabilities also out of schools, Adhikari said. The government has been constructing special residential schools, one in each province, for children with such disabilities, which are expected to come into operation from next fiscal year, Adhikari informed. Still there are challenges as school will be located in specific areas while children having such disabilities are scattered in different parts across the country.

Subash Acharya, Head of the Education Department at Bharatpur Metropolitan City, said except for the children having multiple disabilities the municipality has still noticed the other children out of schools. Acharya said if the schools having few students will merge, children will automatically be deprived from the right to education if there is no alternative management.

Acharya pointed out a flaw in the law, which could ultimately harm citizens’ rights if implemented without proper planning. “Municipalities face serious challenges in providing education to mentally disabled and children with multiple disability,” Acharya added.

However, the Act does make an exception to individuals who are unable to acquire education because of weak health, multiple disability or similar other complex situation.

Education expert Biddhya Nath Koirala believes that the main problem lies in the authorities’ lack of intent rather than resources.

“If the authorities had good intentions, there would be no excuses in implementing compulsory education. Education can be delivered through distance or online modes, and certification can be based on a person’s level of knowledge,” he said.

Meanwhile, the government has also failed to ensure free education even in community schools. Many schools continue to charge minimal fees to cover expenses such as teacher salaries, support staff, electricity, and other operational costs.

Although the Constitution clearly states that “every citizen shall have the right to acquire free education up to the secondary level from the State,” the reality in public schools tells a different story.

Acharya added that schools are unable to strictly enforce the free education provision because of insufficient budget. “Schools are compelled to manage funds for utilities, private resource teachers, and extracurricular activities on their own,” he said.

Education head Acharya said they are also unable to tighten schools as they cannot allocate sufficient budget to manage all requirements of the school. Currently, school are compelled to manage finance, electricity, water, private resource teachers and other extra activities on their own.

Lab Raj Oli, Chairperson of the National Campaign for Education, said the lack of consistent policy and accountability has made the government’s promise of free and compulsory education largely limited to rhetoric.

All these circumstances show that strong government intervention is required for the successful implementation of law or it must be amended to ensure citizens' rights to participation.

-square-thumb.jpg)