- Wednesday, 18 February 2026

Ordeals Of Festivals

Compulsion To Forgo Family Reunion

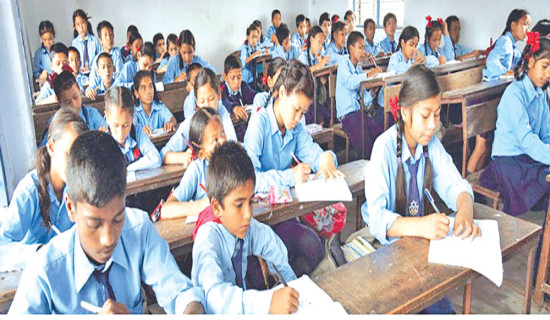

Dashain, Nepal's most significant festival, has long been synonymous with family reunions. Traditionally, it's a time to gather families at one place, meet relatives, and blessings are exchanged. This annual reunion has been crucial in maintaining psychological well-being and cultural strength among Nepalis.

However, in recent years, the changing socio-economic landscape of Nepal has begun to reshape this centuries-old tradition, creating a complex textile of celebration, separation, and adaptation.

Historically, Dashain has been more than just a religious observance. It's a time to reunite, for strengthening family bonds and passing down cultural values to younger generations. The festival, lasting 15 days, sees families come together, especially at their village home, to perform rituals, feast on special dishes, and engage in various forms of merrymaking. Receiving of Tika (a red mark on the forehead) and Jamara (barley shoots) from elders, symbolising their blessings for prosperity and protection, is the main attraction of the festival.

However, the relevance of such gatherings is being challenged by the increasing trend of nuclear families and professional demands that separate family members. This shift is particularly noticeable during festival periods, which highlights a growing issue in Nepali society.

Many lower- and middle-class Nepali families are being separated due to job opportunities, often in Middle Eastern countries and, more recently, developed nations like Australia, America, and others. This economic migration has led to prolonged absences, sometimes spanning years, with family members unable to return home even for important festivals like Dashain.

Sunita Roka, 25, originally from Gorkha married to Niraj Tripathi from Udipur Lamjung in 2018. Their first Dashain together was a special occasion, but shortly after, Tripathi left for the United Arab Emirates in pursuit of better job opportunities. Now, Roka and her five-year-old son haven't celebrated Dashain with Tripathi for six years.

Talking over the phone from Lamjung hospital, where her son is receiving treatment, Roka expressed deep sense of longing she feels for her husband, especially during the festivals and when her child falls ill.

"It is difficult to explain to our son why his father is not here during Dashain when all his friends are celebrating with their father," Roka shared, her voice tinged with sadness. The couple hopes to reunite permanently in Nepal once they can afford their own vehicle. However, they are concerned that driving is not viewed as a respected profession in their society. Roka said if the government could provide reputable job in the home country, families like her wouldn't have to endure long separation.

Another, Shanta Kandel from Bharatpur, Chitwan, has a different story to tell. Despite having a six-member family, Kandel, a cancer survivor, often finds herself celebrating Dashain alone. Her husband and one son work in Qatar, while another son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter live in Cyprus.

"For the past decade, we haven't all been together for Dashain," Kandel shares. "I understand they're working for a better future, but during festivals, the silence in this house makes me cry."

Kandel's experience reflects a growing trend among many families in Nepal. A recent study by the Kathmandu Metropolitan City found that loneliness is on the rise among senior citizens, particularly those whose children have migrated abroad. The study revealed that 21.7 per cent of senior citizens with children overseas suffer from severe emotional isolation, while 63.3 per cent experience moderate emotional loneliness.

These individual stories point to a broader societal issues in Nepal. Sociologist Yuvraj Luintel notes that loneliness is more prevalent among senior citizens in cities compared to villages. He attributes this to a shift from joint families to nuclear families in Nepal's evolving social structure.

"In villages, there's still a sense of community that can somewhat fill the void left by migrating family members," Luintel explains. "But in cities, the isolation can be acute, especially during traditionally family-orientated festivals like Dashain."

Dr. Dipesh Ghimire, a sociologist and assistant lecturer at Tribhuvan University's Central Department of Sociology, points out that the specialised nature of professions within families is decreasing the relevance and values of festivals like Dashain each year.

"When family members pursue diverse careers in different parts of the world, finding a common time for reunion becomes increasingly challenging," Dr. Ghimire observes. "This is gradually eroding the collective experience that made Dashain so significant."

Despite these challenges, many Nepali families are finding innovative ways to maintain their Dashain connections. Video calls have become a common feature of the festival, with families gathering around screens to receive virtual tika from elderly relatives.

Nabin Sapkota, who had been in Australia for five years, said his wife and son used to receive tika and blessings from his father, mother, and grandmother from screen. "During Tika, we used to set up a laptop to receive tika and blessings virtually. It wasn't the same as being there in person, but seeing everyone and participating virtually made us feel connected."

Sujita Pokharel, who has been separated from her husband in Australia for three years due to visa complications, shares her experience that she missed her husband very much during festivals.

The impact of this cultural shift extends beyond emotional well-being. Nepal has seen over 38,000 divorce cases in a year, partly attributed to long-term separation of families. Moreover, remittances from abroad, while crucial for Nepal's economy, are changing the nature of Dashain celebrations at home.

In such a context, finding a balance between economic progress and cultural preservation remains a critical challenge for Nepal in the coming years too. Some possible solutions can be discussed on the issues. The government initiatives to create more job opportunities within Nepal, allowing families to stay together without sacrificing economic prospects. Likewise, introducing the value of festivals in school curricula to set their importance in children from an early age.

The authority can develop policies that facilitate easier travel for Nepali working abroad during major festivals. Similarly, it can also encourage companies to adopt family-friendly policies that respect cultural traditions.

(The author is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)