- Friday, 27 February 2026

Winter drought hits farmers hard in Tarai

Kathmandu, Dec. 28: Mahashankar Thing, a sugarcane farmer from Gaushala Municipality in Mahottari district, is struggling to save his crop as the winter drought tightens its grip in the central Tarai.

With no rainfall for almost two months, his sugarcane fields -- normally green and thriving at this time of year -- are showing signs of stress and disease.

The prolonged dry spell has weakened the plants, allowing fungal infections to spread across the plantation. At the same time, dense fog has lingered over the area for days, blocking sunlight and creating worst conditions that further favour disease. Cold temperatures and heavy morning dew have added to the damage, slowing growth and reducing the plants’ ability to recover.

Sugarcane, a water-intensive crop, depends heavily on regular moisture during the winter months. Without rainfall, soil moisture has dropped sharply, forcing farmers to rely on limited irrigation.

For many, pumping groundwater has become costly and unsustainable, while others have no access to irrigation at all. As a result, cane growth has stalled, and the risk of yield loss is increasing with each dry day.

Not only Thing, many farmers in Mahottari watch the sky daily, hoping for rain to clear the dense fog, restore sunlight and revive their fields. “Rain is the only solution now. Without it, the crop will not survive,” Thing said.

A news report published in The Rising Nepal a few days ago said farmers in Dang district have reported wheat and barley fields drying up in mid-winter. Similar conditions have been observed in Mahottari and other districts of Madhes Province, where declining soil moisture and drying irrigation sources have affected wheat, mustard and sugarcane as well as other winter crops.

Nepal has been experiencing a severe winter drought for the past three consecutive years, with the country receiving less than 5 mm of rainfall during the winter.

Winter rainfall contributes about 10 per cent of the annual total precipitation, while nearly 80 per cent occurs during the monsoon season.

This year marks another dry winter in a growing pattern of prolonged droughts, raising serious concerns about water availability, agriculture and environmental stability, experts said.

The Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) has forecast below-average rainfall across most parts of the country this winter as well. According to a winter outlook issued by the Climate Division under DHM, most areas are likely to receive less rainfall than normal during the three winter months (December to February).

The immediate impact is already visible in farmlands across the country. Winter crops such as wheat, barley and mustard are drying up during a crucial growth period.

Winter droughts becoming a recurring pattern

According to DHM, winter droughts have occurred frequently over the past two decades, including during 2006-2011, 2016-2018 and again from 2021 onwards. This trend suggests that winter droughts are no longer occasional phenomenon but a recurring feature of the country’s changing climate.

Bidhya Maharjan, an agro-meteorologist at DHM, said drought conditions have been increasing due to a lack of winter rainfall. She explained that monsoon rainfall has become more intense but occurs over short periods, causing most of the water to flow away rather than soak into the ground. Winter rainfall, although accounting for only about 10 per cent of the annual total, is crucial for crops as it helps retain soil moisture.

“Rainfall during the monsoon season was normal this year, but much of it fell within a few days. This raises the overall average, but the water does not spread evenly or penetrate the soil sufficiently to benefit agriculture,” she said.

Infiltration rates have declined due to rapid urbanisation, while soils are drying faster because of current agricultural practices, including the excessive use of chemical fertilisers. She added that global warming has also contributed to a steady decline in groundwater levels across the region.

“Groundwater does not follow political boundaries. In many cases, the recharge and extraction points are located in different areas,” she said. “In the Tarai region, heavy groundwater extraction across the border in India could reduce the amount of water available on the Nepali side.”

Research points to growing drought hotspots

A report by ICIMOD, “2025 Drought in Nepal’s Madhes Province: A Rapid Situational Analysis”, published on August 21, 2025, described the drought as a “slow burn” disaster. It showed how a lack of rainfall gradually turned into a serious agricultural and socio-economic crisis.

The report said that although the 2025 monsoon arrived early in some parts of the country, Madhes Province -- often called the country’s “grain basket” -- continued to face a severe dry spell that began in the winter of 2024-2025.

According to the report, about 30 per cent of community boreholes and shallow tubewells in Madhes dried up completely.

This is particularly worrying as the province depends heavily on groundwater when rainfall is insufficient.

The report also stressed that the ecological health of the Chure Hills is crucial for recharging groundwater in Madhes. However, deforestation and unregulated mining in the hills have reduced the land’s ability to absorb rainwater, resulting in falling groundwater levels downstream. The exceptionally dry winter of 2024-2025 further worsened the situation, leaving soil moisture at record low levels even before the 2025 monsoon began.

On July 23, 2025, the government also officially declared all 136 municipalities of Madhes Province a crisis zone.

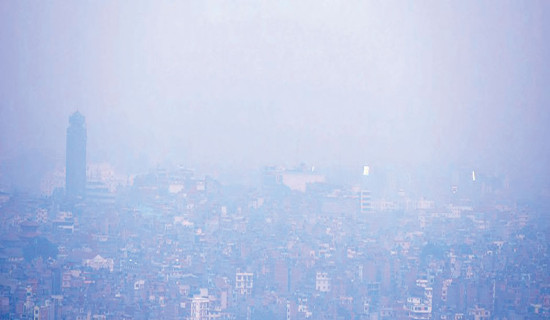

Beyond farms: Snow, fires and air pollution

According to Ngmindra Dahal, a water and climate expert, drought is not confined to farms alone. He said winter rainfall is crucial for snowfall in the mountains, which serves as a natural water reserve throughout the year. A decline in winter rainfall leads to reduced snow accumulation, directly affecting groundwater recharge and river flows.

“Snowfall during December and January usually lasts for four to five months, gradually releasing water into rivers and aquifers,” Dahal said. “However, off-season snowfall does not persist for long. Although rainfall in October this year triggered some snowfall in mountainous areas, it was not sufficient compared to normal winter snowfall.”

Another major impact of winter drought is the increased risk of forest fires, which in turn worsens air pollution. Even a small amount of winter rainfall can make a significant difference.

“Just 5 mm of rainfall during winter would be beneficial, as it would soak into the ground, reduce risk of fire and help ease pollution levels,” he said.

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA), eight people lost their lives and 55 others were injured in fire incidents between November 11 and December 11 across the country.

Climate experts said the drought has been driven by weak western disturbances -- the weather systems responsible for winter rain and snowfall in Nepal. This year, their impact has been further reduced, resulting in an almost rainless winter and worsening drought conditions across much of the country.

-square-thumb.jpg)