- Wednesday, 11 March 2026

Late-monsoon deluge triggers deadly landslides

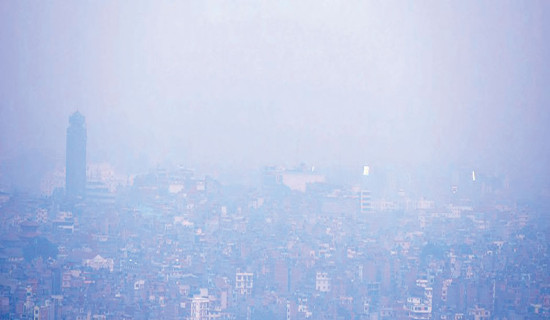

Kathmandu, Oct. 19: The late-monsoon rain that arrived in the first week of October this year turned deadly across the country, claiming at least 53 lives, with several persons still unaccounted for.

Ilam, in the eastern part of the country, became the epicentre of the tragedy, where a powerful overnight landslide swept through settlements, killing 39 people in a single night.

The disaster followed an extreme weather event that brought 332.6 mm of rainfall in just 24 hours on October 5 in Himali Gaun, the highest single-day total ever measured in Ilam. Second highest was measured in Ilam was 286.2.

Lumle in Kaski received the highest rainfall this year, measuring 4,890.3 mm, while the second highest was recorded at Charikot with 3,055.5 mm during the monsoon period. However, the highest single-day rainfall was measured at Maheshworpur station in Rautahat district, recording 368 mm on October 5.

Experts said that the intensity and timing of such rainfall point to a growing pattern of erratic monsoon behaviour, leaving mountain communities increasingly vulnerable to sudden and catastrophic landslides.

Watershed expert Madhukar Upadhya said the monsoon this year both began and ended with disasters. Its onset brought heavy rainfall and destruction, followed by a dry spell lasting at least five weeks initially (Tarai became fully dry), while its withdrawal once again ended in tragedy.

This year, the monsoon began on May 29, almost two weeks earlier than the usual onset date, and retreated on October 10, about a week later than the normal withdrawal date of October 2, according to the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM).

According to meteorologist Sudarshan Humagain at the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM), Nepal recorded 1,375.4 mm of rainfall this monsoon, which is 97.2 per cent of the average monsoon rain and is categorised as normal rainfall.

The DHM defines normal rainfall ranging between 90 and 110 per cent of the total rainfall during the monsoon period, which amounts to 1,414.5 mm for the season.

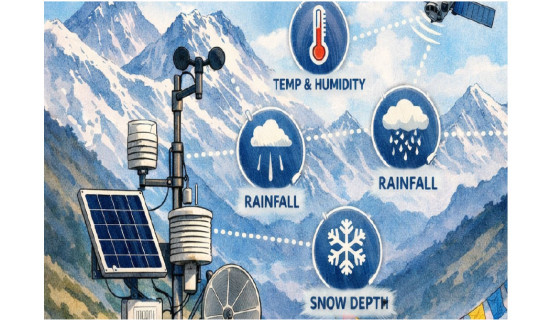

Improved early warning

The accuracy of monsoon forecasts has become increasingly relevant due to improvements in the country's forecasting system. Recent examples highlight the life-saving potential of these predictions, from the Sindhupalchowk flood to last year’s devastating rainfall in the Kathmandu Valley, and a timely forecast issued during Dashain this year.

Binu Maharjan, a senior meteorologist at the Meteorological Forecasting Division (MFD) under the DHM, said that technological advancements have made local level forecasting easier. “However, we are still unable to reach specific areas like individual municipalities,” she explained. “We are currently providing forecasts at the district level. To give specific local area warnings, we lack the necessary advanced technology.”

“We had already issued a red alert for the eastern part of the country, but Ilam was not included in that initial warning. The weather system moved so rapidly that we had to issue another bulletin giving a red alert specifically for Ilam for October 5 to 6,” she said.

She added that the event happened before the forecast date due to the system’s speed. “The system moved so fast that the event occurred before the given date,” she added.

Kedar Thapa, Mayor of Ilam Municipality, acknowledged receiving warnings about the possible disaster. However, he stressed that the timing of the event contributed significantly to the high casualty count.

“We had already received the warning for a possible disaster. But the disaster happened during the nighttime, so we had to bear more human casualty,” he added.

According to Thapa, the floods and landslides caused extensive physical damage across Ilam, displacing hundreds of families. Preliminary data shows that 132 houses were completely destroyed, while more than 400 others sustained partial damage. Ilam Municipality alone suffered losses of around Rs. 1 billion, he added.

The Mechi Highway, a key route connecting Ilam to the national road network, was completely blocked by landslides, along with the Kanchanjunga-Kechana and Nepaltar-Biblyate alternate routes. Damage to the Mechi Highway alone was estimated at over Rs. 3 billion.

Several bridges were swept away as swollen rivers such as the Mai, Puwa and Jogmai overflowed, destroying two permanent bridges, five motorable bridges, and one suspension bridge.

Changing climate pattern

Meteorologist Humagain said that there has been a change in the climate pattern. The duration of the monsoon has been increasing, as the onset remains roughly the same while the withdrawal has been gradually shifting later. Looking at data from 1996 to 2025, in 22 years the monsoon withdrew in October. While the official withdrawal date is October 2, in many years it occurred in the first or second week of October, indicating a shift in monsoon patterns. “Since 2013, the monsoon has consistently been withdrawing in October,” he said.

He said that the shift in the monsoon has been affecting seasonal patterns. October, which used to be mostly dry, is now experiencing rainfall. Previously, such rainfall was mostly linked to cyclonic systems in the Arabian Sea, but now it is increasingly caused by lingering monsoon rains, he added.

The recent precipitation patterns have become highly erratic, according to Upadhya. He said that although the monsoon onset traditionally occurred early, it experienced drought conditions for at least four weeks after the monsoon officially began, a pattern similar to last year.

Upadhya described the disruption in precipitation as highly destructive, stressing that the rainfall is no longer easy to categorise or predict. He explained, “This time, the rain was not just high in intensity but lengthy as well. The overall pattern is different and unlike anything we can easily analyse or model with existing data.” This unpredictability is what makes the current weather situation so devastating.

The historical markers of the traditional rainy season are also disappearing. Upadhya referenced the traditional celebratory days of the monsoon season, Ashar 15, Shrawan Jhari (monsoon shower month) and Bhadaure Pani (late-August/early-September rain), stating that these predictable seasonal rains are no longer reliable.

Climate emergency

Manjeet Dhakal, climate change expert and Head of the LDC Support Team at Climate Analytics, said that recent floods and landslides across South Asia are not isolated events; they are clear signals of a rapidly escalating climate emergency. Scientific evidence, including the IPCC’s findings, confirms that a warmer atmosphere is amplifying rainfall and driving more frequent and intense floods.

A climate attribution study of the September 2024 floods shows that the impacts were significantly heavier and far more likely because of human-induced climate change. These disasters threaten our hard-won development gains, livelihoods, and even national security, Dhakal said.

“We urgently need stronger early warning systems, climate-resilient planning, and global action to cut fossil fuel dependence before these extremes worsen further,” he said.

A new IPCC chapter also highlighted a stark increase in the frequency and intensity of weather and climate extremes globally and regionally since 1950, with human-induced greenhouse gas emissions confirmed as the primary driver.

The report, which updates knowledge since the last major IPCC assessment (AR5), focuses on extremes like temperature spikes, heavy rainfall leading to floods, droughts, storms (including tropical cyclones), and concurrent, multivariate events (compound extremes).

The report also stated that the likelihood of extreme events that are unprecedented in the observed record will increase with rising global warming, even if warming is limited to 1.5 degrees.

Anthropogenic activities

Geo-hazard expert Dr. Basanta Raj Adhikari said that in recent years, the monsoon has tended to become more active during its withdrawal phase. However, he said that trends observed over just three or four years are not enough to draw firm conclusions, as long-term data is needed for accurate analysis.

“The floods and landslides occurred due to intense rainfall over a short period rather than prolonged precipitation. But that is not the only reason, human activities play a major role in triggering seismic and rainfall-induced hazards,” Dr. Adhikari, who is also Director at the Centre for Disaster Studies, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, said.

The combined impact of seismic and monsoon activities is increasing the trend of disasters, Dr. Adhikari said. In many areas, there is no proper drainage system to manage extreme rainfall and the high volume of rain often damages poorly engineered roads.

A study conducted in Sindhupalchowk found that landslides occurred on both sides of road alignments (100 metres left and right), indicating that the combination of road construction and heavy rainfall, a compounding effect, contributed significantly to the damage, he informed.

According to experts, while extreme rainfall was the immediate trigger, unplanned road construction and weak slope management practices are thought to have increased the risk of landslides in various parts of the hilly districts.