- Monday, 28 April 2025

Masinya: Story of injustice meted out against Tamang

By Renuka Dhakal,Kathmandu, Feb. 9; The fundamental principle of law is to ensure equal treatment and protection of basic rights for all citizens, regardless of the community they belong to or the status they uphold.

However, instances are there to show how laws in the past were biased, favouring certain castes over others.

In 1854, Jung Bahadur Rana, the first Rana Prime Minister implemented the ‘Muluki Ain’.

This law divided individuals into specific groups, including ‘Tagadhari,’ defined as the upper caste wearing the sacred thread, ‘Matwali,’ who consumed alcohol, and ‘Achhut,’ referred to so-called untouchables.

Further, the same law divided ‘Matwali’ into two groups, including ‘Masinya Matwali,’ meaning a race that could be killed or enslaved for free, and ‘Namasinya Matwali,’ meaning non-enslavable but alcohol consumers.

Certain indigenous communities like Tharu, Tamang, and Bhote were labelled ‘Masinya Matwali’, who could be enslaved by the ruling elites.

Meanwhile, others like Magar, Sunuwar, Gurung, Rai, and Limbu were placed in the ‘Namasinya Matwali’ category. These classifications not only offended the sentiments of those categorised but also posed a challenge to the principles of humanity and

societal harmony.

Poets Raju Syangtang, Laxmi Rumba, and Rabat have been articulating the injustices, suffering, and humiliation endured by their community through their poetry for quite some time.

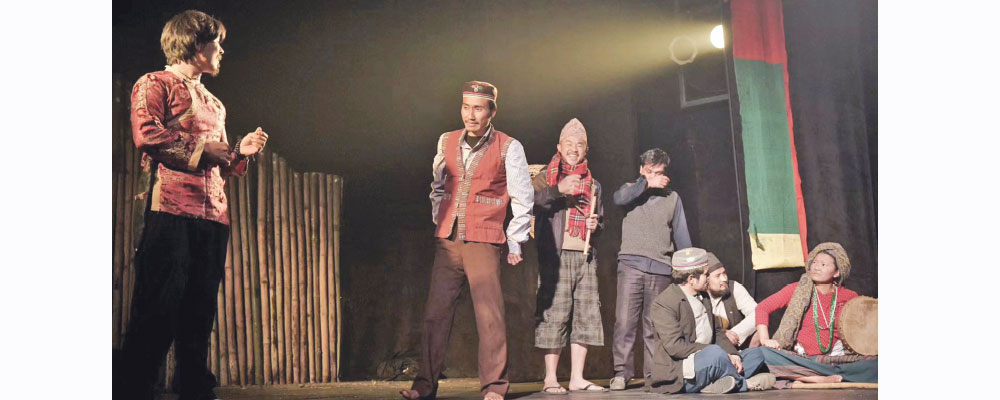

However, this time they narrated their community’s story on stage with the play ‘Masinya’.

The play titled ‘Masinya,’ currently being staged at Mandala Theatre, delves into the lives, cultures, languages, and the oppression faced by Tamang communities due to power dynamics.

The title itself reflects the oppressive categorisation introduced by Jung Bahadur Rana. However, the drama is set against the background of the Maoist insurgency period.

The play depicts the discrimination faced by indigenous people, particularly the Tamang community, for their traditional consumption of beef.

The protagonist, Chyangba, is unjustly arrested and tortured by the police for consuming beef, a practice deeply rooted in his community’s customs for a long time.

The play opens with a ritualistic scene as shamans attempt to heal a mentally ill young woman by chanting mantras and playing ‘dyangro’ (musical instruments used while performing shamanism).

The head Shaman posed questions to an ill girl with chanting mantras, and then the girl started trembling and said she was the spirit of an oppressed Tamang girl.

Then the scene would transport the audience back in time to a Tamang village, the audience witnesses Chyangba meticulously crafting a ‘Chorten’, a symbolic homage to his ancestors.

He seeks to build a ‘Chorten’ in memory of his deceased parents.

However, his plans were thwarted when the local government constructed a road where Chyangba had built the ‘Chorten’, even though the road could have been constructed in another direction.

This incident highlights the disrespect of their culture and faith in the name of modernisation by authority, even in democratic practices.

The play not only revolves around sorrow and pain, it beautifully portrays the liveliness, culture, love story, and natural beauty of Tamang life.

The narrative unfolds the rich culture and emotions, weaving together moments of joy, laughters and tears simultaneously.

The captivating rhythms of Tamang songs, accompanied by the lively tunes of ‘Damphu’ and ‘Tugna’, deeply engage the audience in the performance.

Amidst the serious themes, humorous conversations and mischievous actions between characters in the play in various scenes offer comic relief to the audience.

The drama’s captivating performance, melodious music and the use of light made it an enjoyable experience, but some scenes, particularly the opening scene, felt overly prolonged.

At the end, when Chyangba holds a sword, it shows that the Tamang community wants fair treatment and it tries to convey a strong message that they are ready to fight for their rights if they are not treated equally.

Reflecting on history, the injustices meted out against them in the name of power politics evoke deep emotions and give unbearable pains not only to the Tamang community but also upon all who cherish the morals of humanity.

On the other hand, the play portrays how the Tamang community treats females at home with significant power, often surpassing that of males.

In the so-called upper castes, females are often treated as inferior to males, with male chauvinism and patriarchal norms imposed on them in the name of culture and religion.

However, in the Tamang community, females are treated with honour and respect, which should be learned by all people even in today’s age.

Another highlight of the play is in the Tamang community, where conversations between parents and children are very open, allowing them to share their feelings like friends.

As modern education continuously emphasises the importance of parents understanding children’s feelings and psychology, becoming a friend, a value the many Matwali communities have gracefully upheld for a long time.

Directed and conceptualised by Buddhi Tamang and Sonam Lama, the play will be staged till February 11.

-square-thumb.jpg)