- Wednesday, 4 March 2026

Risk Of Fatal Nipah Virus High In Nepal

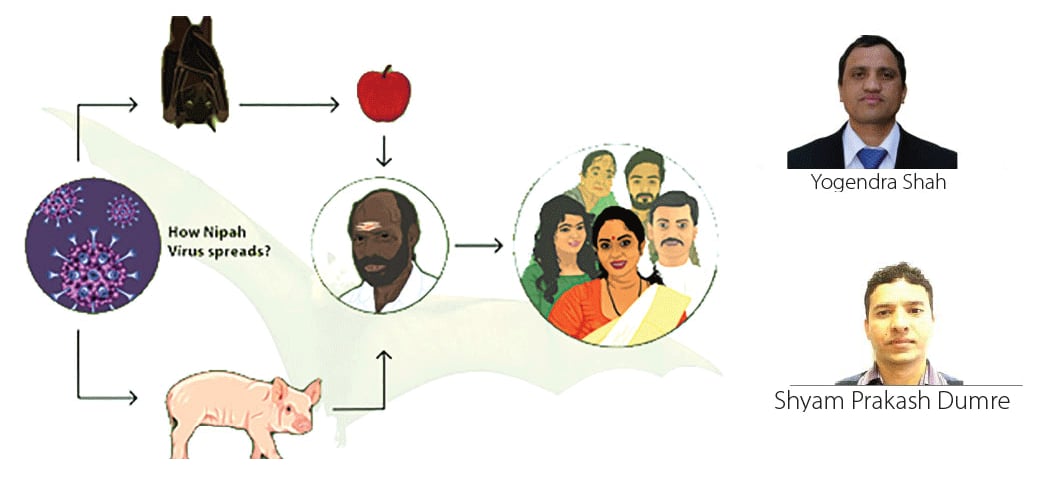

Nipah virus (NiV) is an emerging virus causing severe zoonosis often characterised by severe respiratory disease and encephalitis. A high mortality rate of 40–75 per cent has been reported, mostly from Asia and Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified NiV as a high-risk virus requiring high containment. NiV was named after the village of Sungai Nipah (Nipah River Village) in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, where NiV was first identified in 1999. At that time, the virus crossed the species barrier from bats and infected humans, resulting in highly fatal encephalitis and residual neurological problems among survivors. The outbreak was first recognised in pigs that consumed fruit partially eaten by fruit bats and transmitted the infection to humans. There has been evidence of NiV transmission to humans from animals (bats or pigs), contaminated foods or infected fluids, and it can also be transmitted directly from human to human. In Asia, human NiV cases have been reported since 1998 to date from Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines, totalling 762 confirmed cases and 438 deaths, with an overall fatality rate of 58

per cent.

Outbreaks in neighbouring countries

Several NiV outbreaks with significant morbidity and mortality have been reported in South and Southeast Asia. During 1998–1999, Malaysia and Singapore reported 246 human cases of NiV-associated febrile encephalitis, linked to infected pigs; in Singapore, 11 abattoir workers were infected, with one death.

In India, the first outbreak of NiV occurred in Siliguri, West Bengal, in 2001, followed by the 2007 outbreak in Nadia and almost every year in Kerala since 2018, with 60 deaths alone in 2018. Fruit bat species Pteropus giganteus, Pteropus lylei, and Hipposideros larvatus were confirmed as reservoir hosts of NiV and key sources of virus transmission in India and Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, NiV was first confirmed in 2004, and nine outbreaks were documented between 2004 and 2010.

Further outbreaks in 2011 in northern Bangladesh resulted in 15 deaths. High mortality was associated with the Bangladesh NiV strain. The main reason for NiV transmission in India and Bangladesh was linked to the consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated by fruit bats and partially eaten fruits contaminated by fruit bats through urine or saliva from infected bats. This year, two laboratory-confirmed NiV cases were identified among healthcare workers in Kolkata on 13 January 2026, in India, with no evidence of secondary transmission.

Risk in Nepal

The situation in Nepal differs markedly from that of other South Asian countries. Pig farming has been actively promoted by the government as a poverty alleviation strategy. Despite this, pig rearing in the country is often practised with inadequate health safety measures, creating a high risk of zoonotic disease transmission from pigs to other animals and humans. Moreover, pigs can act as amplifying hosts for multiple pathogens, including Japanese encephalitis virus, NiV, SARS-CoV-2 and rotavirus.

Certain bat species from Nepal (Pteropus giganteus, Rousettus leschenaultii, Eonycteris spelaea, Rhinolophus sinicus, R. affinis, R. ferrumequinum, Nyctalus noctula and Scotophilus sp.) reported that potential reservoir hosts for several viruses are often found in human proximity, and some of them even enter human dwellings at night. Some fruit bats, like P. giganteus and R. leschenaultii, are even consumed as bushmeat by some communities. Conversely, the situation in our country differs from that of neighbouring countries, as one of the major risks for NiV transmission from bats to humans is extensive deforestation, coupled with the growing trend of hiking, camping and human activity in mountainous and forested areas. These factors increase the human–bat interface and consequently elevate the risk of spillover transmission.

Nepal shares open and porous borders with India to the east, west, and south, which poses a high risk for the cross-border transmission of NiV to Nepal. Bangladesh is just 22 km from Nepal’s eastern border (separated by the Indian Siliguri corridor), providing ample opportunity for public movement and disease transmission.

Past experience of larger epidemics and pandemics of infectious diseases like influenza and COVID-19 and preparedness plans made for deadly viruses like Ebola (though we did not face it) are great lessons for disease control authorities. Despite this, we are not fully prepared and need to work more on it.

Therefore, the government and concerned authorities should establish a routine surveillance system to monitor zoonotic diseases at pig farming sites and strengthen safety practices to reduce the risk of transmission to susceptible human populations. In particular, NiV infection in domestic animals such as pigs should be monitored regularly, and farms should be cleaned daily using appropriate disinfectants or detergents to prevent potential outbreaks. Most importantly, human or animal samples with suspected NiV infection need to be handled in a high-containment laboratory, which is not functional in Nepal. Therefore, a preparedness plan should include a clear procedure on coordination with WHO collaborating centres.

Preventive actions essential

To respond to an outbreak, specialised research teams should be established to identify suspected cases of infection in humans and further analyse the possibility of the emergence of new species as potential reservoir hosts of the virus that may be responsible for its transmission to humans from bats.

At border checkpoints between India and Nepal, domestic animals should be strictly quarantined and screened for zoonotic diseases. Furthermore, a One Health approach should be strictly implemented through integrated surveillance and quarantine of domestic animals, enabling early detection and timely warnings for both veterinary and human public health authorities. Additionally, restricting or banning the movement of animals from infected farms to other regions can significantly reduce disease spread.

We should increase public awareness on NiV risk factors and educate people on measures to prevent/reduce NiV exposure and risk of infection. Specifically, public health educational messages should focus on how to reduce bat-to-human transmission, animal-to-human transmission and human-to-human transmission.

Healthcare workers should be made aware of this risk while caring for suspected or confirmed patients or handling samples and should strictly follow the universal standard infection prevention guidelines (i.e., wearing personal protective equipment, an N95 mask, goggles and a face shield) at all times.

A One Health approach would be appropriate to reduce the risk of zoonotic disease transmission. For instance, India has adopted guidelines for the clinical management of NiV disease, using the One Health approach and integrated surveillance. Moreover, establishing mechanisms for cross-border screening, laboratory testing, and diagnostic facilities at points of entry and exit would ensure that suspected cases are referred to provincial/local government-level healthcare facilities. Availability of more reliable tests for the surveillance of communities and livestock will be vital to achieving a better understanding of the ecology of the fruit bat host and transmission risks to intermediate hosts, enabling the implementation of the One Health approach for outbreak prevention and the management of zoonotic diseases like NiV. In summary, the control and prevention of NiV is possible only if strictly endorsed guidelines and control strategies are implemented.

In conclusion, surveillance of NiV and other infectious diseases that could be at high risk of transmission from animals to humans should be carried out. High-risk areas in South and Southeast Asia along the NiV girdle should be identified and mapped, and then continual surveillance should be conducted to facilitate the early detection of virus outbreaks, identify circulating strains among fruit bats, and monitor environmental factors and the dynamics of wide-ranging transmission. A regional coordination mechanism should be developed involving India, Bangladesh and Nepal to prevent the cross-border transmission of NiV.

(Shah holds PhD in Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Japan and is an Associate Professor, Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University and Dumre has completed PhD in Biomedical Sciences, Thammasat University, Thailand.)

-original-thumb.jpg)