- Tuesday, 3 March 2026

Seeing Nepal’s Action Hero Up Close

'Paribhasha' is the only movie I watched twice in the cinema hall. I was a school student in Janata Vidyalaya Tansen during the 1990s. I liked the 'redeemed villain' played by Rajesh Hamal. Although Tulsi Ghimire's 'Lahure' was the first movie that I watched, 'Gopi Krishna' was the one I liked the most. For sure, the double role played by Hamal and the monkey had a long-lasting imprint on the mind of a child. Furthermore, the hero in 'Gopi Krishna' was a macho and had a larger-than-life image compared to the heroes of contemporary movies. The first movie shooting that I observed was 'Deuki' – another film played by Hamal.

During my high-school days in Tansen, two actors dominated our talk – Rajesh Hamal and Dhiren Shakya, both from Palpa. I knew it then that Hamal's father, Chuda Bahadur Hamal, who went to become Nepal's Ambassador to Pakistan, taught at the Padmodaya Public School, which was on the way to my school. We were proud that such a 'great hero' was from our city. And this feeling never went away. As I grew up, I found many other ways to appreciate the actor – he was well-read (During our intermediate studies, we used to say we were studying the same subject as Hamal studied), well-built and well spoken. He could talk about people, culture, literature and cinema. And literally, for a long time, he remained unmatched, at least in the Nepali cinema industry.

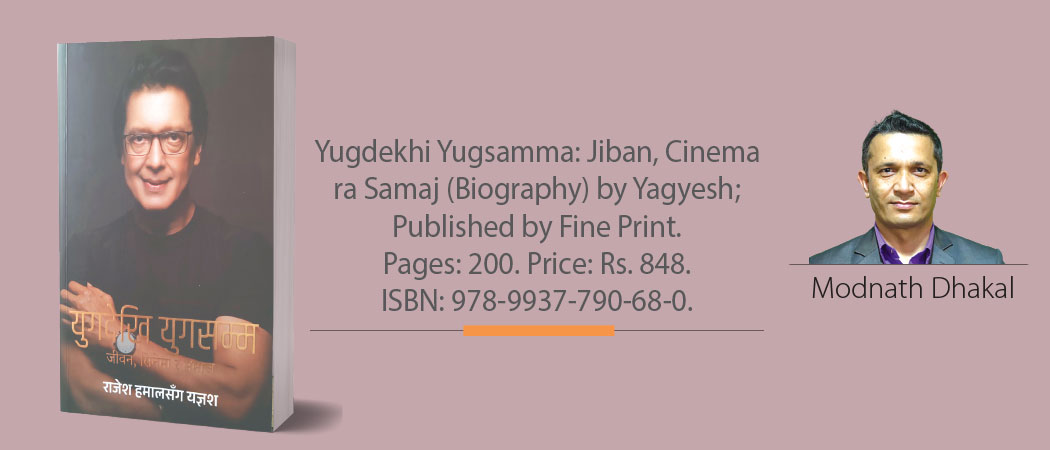

When journalist Yagyesh authored a book on Hamal, I was quick to get a copy and instantly savored it with much enthusiasm and emotion. 'Yugdekhi Yugsamma – Jiban, Cinema ra Samaj' (Rajesh Hamal Sanga Yangesh) is probably the first biography of any Nepali cinema artistes that hit the market in a rather unusual form of presentation – interview format.

Hamal has long been synonymous with Nepali action hero – especially for the millennials. He entered the industry with long hair, a robust body and action skills. He powerfully drew the rural audiences to the cinema halls and even during the decade-long armed conflict, he managed to save his popularity and relevance. As he reveals in the book, he was welcomed and cherished by both the guerrillas and the security personnel.

The book breaks multiple myths. First, people don't like to read interviews because they are boring. Personally, reading conversations is not a choice for me as well. Yangesh's skill and expertise are demonstrated in the presentation of the interview-format biography of the most-favourite artiste of Nepali cinema so far. When I was in the university, I used to regularly read the Indian film magazine 'Filmfare' as I found the language, style and presentation of the content readable and entertaining. 'Yugdekhi Yugsamma' follows a similar style and tone, albeit in the Nepali language.

Although the entire book is a giant interview of a person, readers don't stumble on questions or answers; they flow with the story as it shuttles them between the past and the present. It's a time-travel roller coaster. All the conversations are in-depth and well researched but presented in a lighter tone and readable language. You don't feel you are reading an interview all along but are immersed in the story, ignoring the questions.

Second, cinema professionals don't know much about life and society. Hamal's understanding of society, cinema, politics and human relations has already left many astounded. He has earned a great respect from people for his opinions expressed at various literature festivals and talk shows. He sounds even better in the book.

His neutrality in terms of political philosophy and good understanding of the major political philosophies like communism and democracy amuse readers. He surprises you with his take on 'formula film', spirituality, and religion.

The third, film artists are privileged people who have nothing to worry about. Hamal's life was topsy-turvy during his adolescence and youth. His father didn’t talk to him, he spent more time out of the home, drank a lot, found love multiple times but none stayed with him, and his relationship with his brother was unworkable. But he is among the few artistes who have best understood the film industry vis-à-vis Nepali society, people and politics.

The fourth, biographies present only a selective perception of the writer and vital parts that readers want to know are omitted. Since Hamal talked to Yangesh about his life, experiences and feelings, the latter asked probing questions that might have made other celebrities uncomfortable. But the actor has open-mindedly responded to every type of question. He is happy to share that his fans chanted 'Rajesh Hamal – Jindabad' in Bhairahawa long time back, waited for the whole day outside a cinema to have a glimpse of their favourite actor, and his shootings were disturbed due to their massive turnout.

Meanwhile, he also shares childhood memories -- that he ate all the chickens in Rajhar village of Nawalparasi in pursuit of being like Dara Singh, an Indian wrestler of his time. The book can be a window to peep into the Nepali cinema industry from 1990 to 2015 and develop an understanding of what to expect from it. It is entertaining to read Hamal's view on his typecasting, resemblance to Mithun Chakraborty of Indian cinema, 'Mahanayak' title, and some of his popular dialogues.

You may disagree with me at some points since the book seems to be a tale of a lonely man who is at the top and looking at you, society and cinema from there. Although his bird’s-eye view might seem insufficient to explain the things wholly, you might wonder – although the book gives many reasons – why didn't this 'Mr. Know All' even try to make things better, remake Nepali cinema and redefine his relations with his colleagues, and above all, his family. At times, he seems to have attained the 'Sthitpragya status' – the one who is not affected both by grief and happiness, and is beyond emotions – as mentioned in the Bhagwad Gita.

I enjoyed every part of the book from the beginning to the end and liked the way Yagyesh drives the conversation with the 'top-guy' of Nepali cinema. But even after reading the 300-page book, I am left with many questions in my mind. I would like to know Hamal's personal relations with his colleagues in the cinema, intimate moments with his mother, relations with school-mates, college friends and producers, details on his relations with his wife Madhu before marriage and cinema stereotyping. I am sure, he is saving all this information for his autobiography.

(Dhakal is a journalist at this daily.)

-original-thumb.jpg)