- Friday, 27 February 2026

10-Party Unity: A Struggle For Survival

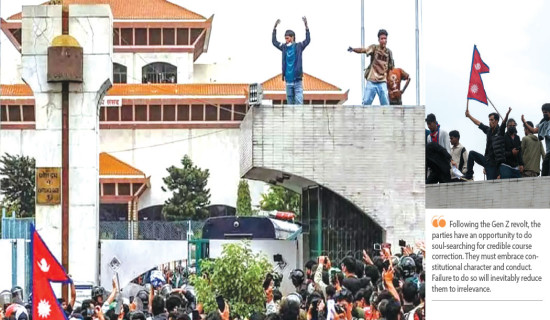

The communist movement in Nepal has faced an existential threat, thanks to the Gen Z movement. This youth revolt emerged independently of the traditional left and democratic party ideologies. The sheer magnitude and swiftness of the youth uprising, which rocked the nation within 48 hours, caught the parties off guard, compelling them to devise a strategy for survival. Consequently, the communist forces are grappling with simultaneous moral, ideological, and organizational crises. However, the ongoing unification drive alone will not enable them to come out of the morass of intractable crisis if they dig their heels in to restructure their organisations.

The recent unification among 10 communist parties, including the CPN-Maoist Centre and CPN-Unified Socialist, was more a marriage of convenience than a convergence of ideas bearing common values, agenda and mindset. With the unity, the two parties also suffered cracks, a bizarre development amidst the efforts of galvanizing the trouble-ridden left movement. However, the birth of the Nepali Communist Party will be a significant moment in the history of Nepali communists if its leaders succeed in translating even a few of their commitments into reality.

The newly formed NCP has received a boost after Bhim Rawal-led Matribhumi Jagaran Abhiyan has unified with it. Rawal, who was the former vice-chair of UML, is known for his nationalistic stand. His entry into the NCP will bolster its position in Nepal's far west.

Guiding principles

Chair of the former Maoist Centre, Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda, has been named coordinator of the new party and former Unified Socialist chair Madhav Kumar Nepal as joint coordinator. In its 23-point declaration paper, the party has adopted Marxism-Leninism as its guiding principles, ‘scientific socialism with Nepali characteristics’ as its programme and the five-pointed star as the election symbol. Prior to the announcement of unity, the constituent parties had inked an 18-point unity consensus paper. To form the new party, Prachanda has shed ‘Maoism’ and Nepal ‘people’s multiparty democracy’ (PMD). The constituent parties have agreed to hold unity convention in six months to pick fresh leadership.

On the other hand, Nepal and Jhalanath Khanal, respected leader of the dissolved Unified Socialist, often used to cross swords over the party’s guiding ideology. Nepal insisted on ‘people’s multiparty democracy’ but Khanal stressed socialism with Nepali characteristics, arguing that the country has already attained people’s multiparty democracy with the Janaandolan II. But Nepal has now agreed on Marxism-Leninism as the main theoretical basis for the new party. Quite interestingly, Khanal initially stood against the unity with the Maoist Centre, showing reservations about its involvement in the decade-long Maoist insurgency. But eventually, he joined the unity declaration meeting of 10 parties after the CPN-UML shut the door for his entry.

The moment of unification also turned out to be a bit of a damp squib as some influential leaders of the dissolved Maoist Centre and Unified Socialist refused to join the newly formed Nepali Communist Party. Deputy general secretary of the Maoist Centre Janardan Sharma and general secretary of the Unified Socialist, Ghanshyam Bhusal, opposed the unification, accusing their leadership of not wanting to pass the mantle to a new generation of leadership. In fact, both Sharma and Bhusal have no qualms about the ideology of the CPN but they have been demanding restructuring of their respective parties. Sharma has formed the Progressive National Campaign under his convenership, accusing Prachanda of ditching ‘Maoism’ for the sake of holding on to the leadership.

Interestingly, Bhusal refused to be a part of the new NCP touted to unite the Nepali left movement. While in the Unified Socialist, he pitched for the socialist programme and termed the PMD as outdated. As the newly created NCP followed the ideology and programme that he has been advocating for years, he took a U-turn. He has demanded that Prachanda and Nepal step down from their position and pave the way for the younger generation leadership as a precondition to join the bandwagon. Bhusal has joined hands with former Maoist leaders Sharma and Netra Bikram Chand Biplav to build a broader alliance of communists, socialists and patriots to end the current deadlock in national politics. When he is ready to ally with former Maoist stalwarts, then why is he dragging his feet to be part of the NCP? This is the question the cadres of the new party are posing.

Burden of transitional justice

Nonetheless, a sizable number of cadres and leaders of the Unified Socialist were against the idea of uniting with the Maoist Centre, for they saw it not as unity, but merger into the Maoist Centre, which has a larger organisational base. Moreover, both parties originated from different schools of thought. Former Maoist rebels glorify their decade-long insurgency in which 19,000 people were killed. Thousands of conflict victims cry foul for not being given justice. Now the leader Nepal and his colleagues have to also share the burden of transitional justice, to which they were not a party. The Unified Socialist, a splinter of the UML, rose from the parliamentary politics. How can two opposite ideological groups assimilate under the same banner?

The NCP has vowed to realise the aspirations of Gen Z but some observers argue that Prachanda and Nepal formed the new party to avoid the mounting pressure to pass the baton to the younger leaders. The series of divisions and unity among the Nepali communist parties is not a new phenomenon. As the Gen Z revolt overthrew a powerful coalition government under a communist leader, the communist parties have faced a crisis of legitimacy. The formation of the new communist party is also a gambit to counter the UML which is now on the defensive.

(The author is Deputy Executive Editor of this daily)