- Monday, 23 February 2026

Parenthood Beyond Cultural Duty

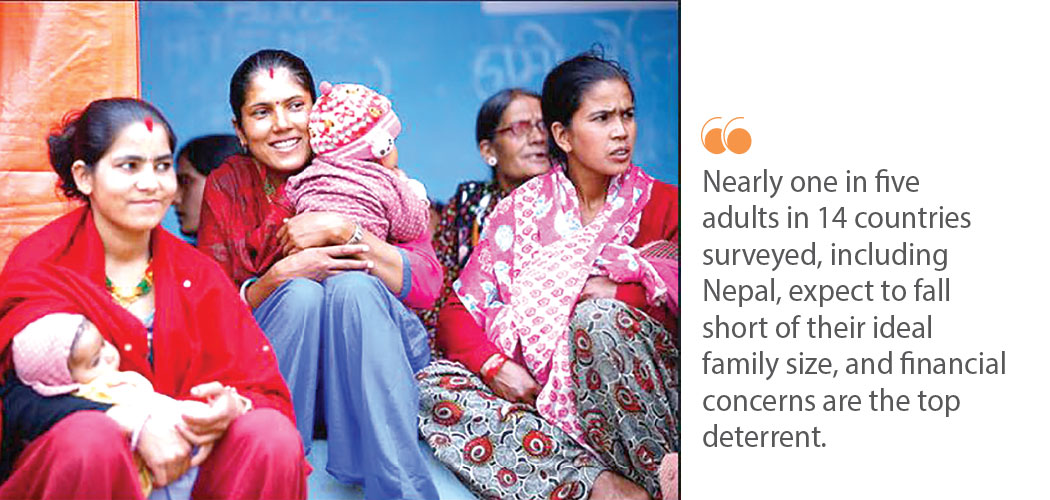

In Nepali society, childbearing is considered a duty and not a choice, owing to intense cultural pressures that are significant to family tradition and precedent. At the same time, economic pressures in the form of rising living costs, unemployment insecurity, and lack of childcare make family life difficult to sustain. Social expectations are more important than individual concerns regarding health, work, or household size, and put pressure on couples.

Cultural expectations and gender inequality continue to limit choice, with others not yet being in the position to have the family size that they truly desire. The 2025 UNFPA State of World Population report is a good reminder that the "real fertility crisis" is the difference between the families

people want and those they can afford. Nearly one in five adults in 14 countries surveyed,

including Nepal, expect to fall short of their ideal family size, and financial concerns are the top deterrent.

That nervousness is already evident at home. While most individuals wish to have children, gender disparities, inadequate childcare, economic instability, and restrictive national policies hinder them from creating the families they desire.

Nepal's general fertility rate fell from 4.6 children per woman in 1996 to 2.1 in 2022. Yet most couples still say they want two or more children. Field data from UNFPA shows the most significant gap in urbanised provinces Bagmati and Gandaki, where childcare, housing, and unstable economic employment make having children appear to be a financial risk.

Globally, 39 per cent of would-be parents cite money as the most significant obstacle. Nepali couples do the same, as rent and food costs exceed wages. Migration makes it worse. Over the past three decades, 6.8 million Nepalis have taken foreign jobs, with another 170,000 leaving in the first quarter of the current fiscal year. Spousal separation means many women shoulder solo caregiving while men miss the early years of their children's lives—or delay parenthood altogether. Remittances sustain households through life, but not in the manner of a second set of hands or the arithmetic of feeling with which one begins (or contributes to) a household. Demography is also inevitably tilting towards senility. Seniors comprise 9 per cent of the population; in 2061, one in five Nepalis will be over 60. Without a correction, tomorrow's shrinking streams of workers will remit pensions, medical attention, and debt service to an enlarging elder class—a tall order if today's young adults are kept shut out of safe work, affordable housing, and reproductive health care.

And then what should policymakers do? First, treat reproductive choice as an economic stabiliser, not a privatised luxury. That means investing in universal, first-class sexual and reproductive health services—from contraception to fertility treatment—so that couples can space births. Second, enshrine liberal, sex-free parental leave and flexible working arrangements. Caregiving will be feminised until men are brave enough to take a break and employers stop penalising parents of either sex.

Third, low-cost childcare should be expanded in urban core areas, where service-industry schedules clash with school hours. Fourth, banks and local governments should be encouraged to initiate rent-to-own and cooperative housing initiatives that give young families a share in housing markets.

Finally, remittance streams can be drawn on by offering matched savings or diaspora bonds focused on child-friendly infrastructure.

One policy cannot ensure, nor can it ever aspire to, a baby boom. Instead, policies should make conditions favourable for Nepali couples to have children, driven by hope rather than fear. Suppose individuals have confidence that society will nourish having a family.

In that case, population levels will automatically stabilise, for authentic solutions to low fertility are not offered by decree or money incentives, but by popular confidence in society's support.

(Rijal is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)