- Sunday, 22 February 2026

The Sideline Story Of Bijukchhen

Narayan Man Bijukchhen, also known as Rohit, is a prominent communist leader who is distinguished by his lifelong commitment to politics, culture, and literature. Despite his substantial responsibilities as chairman of the Nepal Workers and Peasants Party, he has consistently prioritised intellectual pursuits, including extensive reading, writing, and cultural engagement. Jelka Chithiharu (Letters From Jail) stands out among the many books to his credit. Recently translated into English, it unveils his sideline stories.

On 21 August 1988, a devastating earthquake struck

Nepal, severely damaging Bhaktapur also. The government promised relief

measures, and on 25 August, a distribution programme was organised. Coupon

distribution was led by former Rastriya Panchayat member Karnaprasad Hyaju, who

was not even a Relief and Rescue Sub-committee member. Victims, however, did

not receive the coupons; many of those who did were unaffected by the quake.

Outraged, the crowd dragged Hyaju to the damaged sites. He was assaulted while

the police stood by, doing nothing. Injured, Hyaju was eventually taken to the

hospital, where he died later that night. This incident became known as the

Bhaktapur Case.

Soon after, police arrested activists, including

Rohit, then chairman of the Nepal Workers and Peasants Organisation, accusing

them of involvement in Hyaju’s death. His four brothers were forced to go

underground. With a strong grassroots base among farmers, the organisation

emerged as a threat to the Panchayat regime. The government of Marich Man Singh

saw an opportunity to crush it by charging its leaders. Members were either

imprisoned or driven underground, while police harassment at their homes became

routine.

Rohit was detained in different places across

the Kathmandu Valley. His wife, Shova Pradhan, was a local school-teacher and

an ordinary housewife. When her husband was jailed and her brothers-in-law

forced underground, she had no one but her elderly mother-in-law and her

four-year-old son Subeg. At that time, she was also pregnant. Every day the

police came looking for Rohit’s brothers, and when they did not find them, they

would issue threats to Shova and her mother-in-law. They would forcibly take

away books and belongings. Not involved in politics or organisational work in

any way, Shova was utterly helpless at the time.

On her way to and from school, she faced many

slanders. Carrying her four-year-old son on her back, she would visit her

husband in various prisons. Seeing the immense pain hidden behind her faint smile,

Rohit would be deeply moved, yet he never let it show.To inspire his wife, keep

hope alive, give her political and social instruction, and help her understand

the strength and significance of the organisation, Rohit wrote to her

continuously. Always busy awakening workers and peasants before, Rohit used

these letters that time to share many things about his past, education,

literature, history, heritage, culture, and society in simple language.

Starting from matters of health, diet, and neighbours, he would gradually enter

more serious subjects.

Those very letters are collected in 'Letters From Jail'. Reading them not only reveals Rohit’s immense

knowledge of history, heritage, and literature beyond politics, but also gives

a clear sense of who he was as a person. He would spend his days, and in

certain situations, entire nights, working among workers and farmers. How did

he ever find time to study such deep topics beyond politics? Rohit explains,

"Politics and organisation are not enough; politics also means a deep

understanding of society. I learned many things from the people, and I used my

sleeping and resting hours for writing and study."

His youngest brother, Yogendra Man Bijukchhe,

recalls that whenever Rohit was at home, he was always writing something or

reading newspapers, journals, or books and taking notes. "It was not certain when he would come home or

where he would be. But at home, he would spend most of his time reading and

writing." This is also reflected in 'Letters From Jail', where Rohit would often request his brothers to send

him various newspapers and books.

Indeed, in the letters Rohit, with deep

feelings, described the books he had read, the songs he had listened, and other

topics he knew about. He discussed almost all of Nepal’s nationally recognised

writers. He recounted first meeting with Laxmi Prasad Devkota and Balkrishna

Sama in a literary conference in Gaur, and later meeting them again at the

Birat Nepal Bhasha Literature Conference in Bhaktapur. In world literature, he

mentioned the works of Dostoevsky, Yasunari Kawabata, Premchand, Rabindranath

Tagore, Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyay, and Bhishma Sahni, as well as Indian

actress Shabana Azmi's films and Safdar Hashmi's plays.

He also included delightful and interesting

anecdotes from children’s literature, folk literature, and education. So strong

was the impact of these letters that Shova came to understand the value of the

organisation and herself became active in the Nepal Revolutionary Women's

Association.

During his involvement with the Communist

Party of Nepal, Rohit had spent some time in political exile in India, so it

was natural for him to write about Indian society, and Bengali literature. Yet

it is amazing to see his deep knowledge of dance, painting, sculpture, and heritage.

When Rohit learned his eldest son Subeg's interest in fine art, he wrote to

Shova about various aspects of art in a way that would satisfy their son's

curiosity. Explaining the meaning of gestures in dance, he wrote, "When a

dancer forms a triangle with the index finger, middle finger, and thumb of the

left hand, touches it to the chest, raises it to the face, spreads it open, and

extends all five fingers, it means, 'My heart blossomed like a flower.'

Similarly, when she spreads all five fingers, shakes the hand, and brings it

down from above, it means, 'It is raining.'"

Rohit’s reflections on love and marriage are

even more captivating, revealing the tender feelings of a leader devoted to the

people. At one time, gossip in the community had made Shova wonder whether she

might be his second wife. She had even asked him about it. Though Rohit assured

her that she was his only wife, he had not told her about his earlier marriage

proposal.

Once, in Darbhanga, India, he had taken some

women and children to watch a movie at their request. While crossing the

street, a little girl could not step over water flowing along the roadside, so

he lifted her in his arms. At that very moment, two rickshaws passed in front

of them carrying people from Bhaktapur who knew him, and they were laughing.

Based on this, rumours spread that Rohit had a wife and children. Even his

other relatives repeatedly questioned him about it.

In his youth, he had indeed a marriage

proposal from a cultured, beautiful and loving young woman. At the time, he was

living in a rented room, and kitchen utensils, bedding, and a mosquito net were

purchased in preparation. The girl, her mother, and their relatives were very

fond of him. Her father, however, had a different view, "The boy is involved

in politics; our daughter's life will be tough."

Back then, Rohit was a teacher at a local

school, giving tuition in the mornings. He was asked to come to the girl's

house at 12 PM for fixing the wedding date. That very morning, farmers paraded

the corrupt chairman of a cooperative around the town who had refused to

provide fertiliser to them. By 11 AM, Rohit was ready to go to the girl’s

house. Just then, a group of policemen appeared. Some people warned him,

"Run! The police are coming to arrest you." Dodging them, he made his

way through one alley after another, while the police arrested the farmers.

Following his friends' advice, he left the district.

When he returned six months later, the

farmers were in custody. Once again, men came from the girl's family to renew

the marriage proposal. But Rohit told them, "My friends are in prison, how

can I celebrate a wedding?" The girl waited for three or four years, but

as his friends were not released, Rohit expressed his inability to marry.

Eventually, the girl married elsewhere. Thus, the marriage of a communist

leader slipped away. It was only at 44 when Rohit finally got married to Shova,

a teacher from Ramechhap. Sad to say that Shova died of cancer at 62, three

year ago.

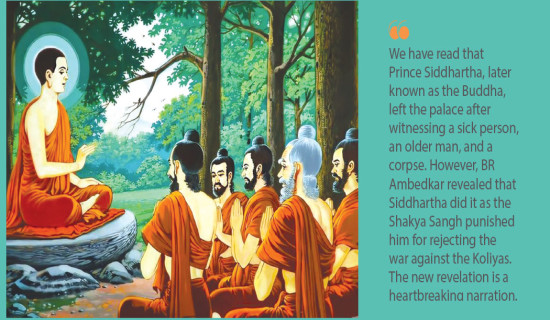

Back in Gaur, it was Indian teacher Chintaharan Singh who planted in him the seeds of compassion and simplicity, while communist activist Leelaraj Upadhyaya instilled the ideas of communism. To this day, his ideals remain the great communist leaders Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao, Stalin, Ho Chi Minh and Kim Il Sung. Yet, never tempted by the lure of power, he seems as tranquil as the Buddha himself.