- Sunday, 22 February 2026

Buddha's Courageous Moral Stand

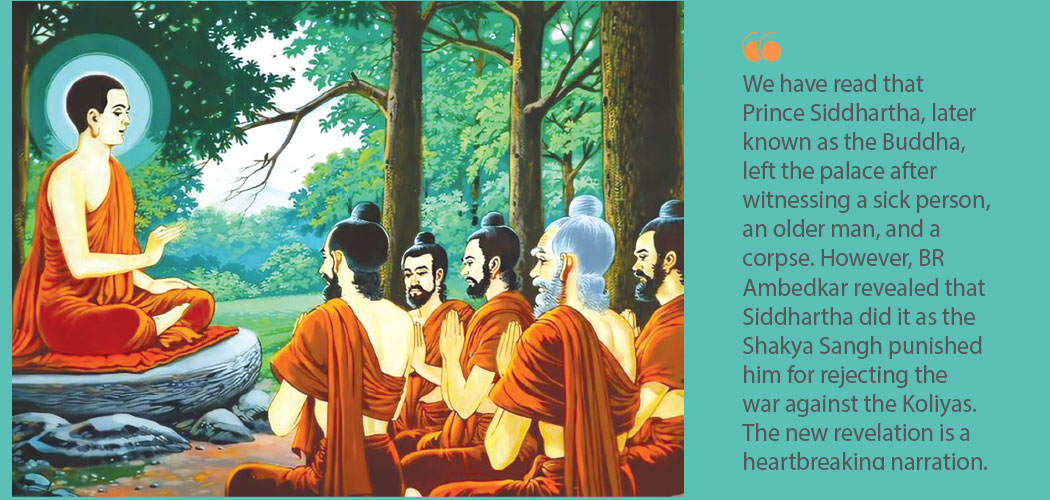

In Herman Hesse's acclaimed novel 'Siddhartha', the Buddha says, "Suffering cannot be overcome by logic and cunning. Instead, guard them." The Buddha himself guarded them so long as he lived. In his youth, he renounced his princely life and left the palace. Was it really because of those three sights—of the sick, the old, and the dead, as we have read ? BR Ambedkar said no—not at all.

The book 'Buddha and His Dhamma', by BR Ambedkar, the architect of India's Constitution and a renowned Dalit scholar, offers a startling revelation. After 35 years of rigorous study, Ambedkar concluded that Prince Siddhartha left the palace not out of emotional despair but because he found himself powerless and silenced as he advocated for peace during the Rohini River dispute. Even other Buddhist scholars, such as Acharya Dharmanand Kosambi, questioned whether an intellectually advanced 29-year-old like Siddhartha could have reached that age without ever witnessing illness, ageing, or death.

Satyagraha

According to the book, published in 1957, Siddhartha faced an unimaginable crisis when, after eight years of service in the Shakya Sangh, he rejected traditional norms in favour of peace, justice, and truth. In the Shakya Republic of Kapilvastu, the Sangh functioned like a modern parliament. Every male over the age of 20 was a member. As per tradition, Siddhartha became one too. Members had to pledge to protect the state with body, mind, and wealth; point out wrongdoing without fear or favour; and atone for personal misdeeds. Members involved in crimes like rape, murder, theft, or perjury would be expelled.

For eight years, Siddhartha was considered a conscientious and courageous member. However, then came the crisis. The Rohini River, which flowed between the Shakya and Koliya states, was used by both. Disputes over irrigation rights were frequent, sometimes even violent. When Siddhartha was 28, a major conflict erupted. Farmers from both sides were seriously injured. As tensions escalated, both sides leaned towards war.

The Shakya Senapati (army general) convened a meeting and proposed a war against the Koliyas. Siddhartha opposed it, saying, "War solves nothing. It achieves no real purpose. One war only plants the seed for another. Those who strike others will themselves be struck. Those who conquer today will be defeated tomorrow. Those who destroy others will one day be destroyed. Let us not rush into war. We must first investigate who was at fault. I have heard it was our people who initiated the violence. If true, the blame is partly ours."

Indeed, the Shakyas had attacked first. The Senapati tried to justify this by claiming the Shakyas were first in line for irrigation. "Even so, we are not free from blame," Siddhartha replied. "Let us appoint two representatives from each side, who can choose a fifth person to resolve the matter impartially."

In the Mahabharata story, despite a hostile relationship between the Pandavs and the Kauravs, the Pandavs rescued the Kauravs from the Gandharvas because they were their cousins. Contrarily, for Siddhartha, truth, peace, and humanity took precedence over nationalism. He said, "Seeking peace amid injustice is futile." The Senapati, filled with Kshatriya arrogance, rejected Siddhartha's logic and argued that the Kshatriya, the warrior caste, were bound by dharma to fight. Siddhartha replied, "The essence of dharma is that hostility cannot be cured with hostility. Only love can overcome hatred."

Although a vote authorised the commencement of hostilities, Siddhartha, echoing Socrates' earlier dissent, found himself in opposition to the majority. The general's proposal for war was approved, leading to the subsequent conscription of men between the ages of 20 and 50. Siddhartha maintained his unwavering objection. He stood up and said, "Friends, do as you see right. The majority is with you. But I cannot participate in this war."

Originally independent, the Shakya state had fallen under the control of King Pasenadi of Kosala. The Shakya state could no longer make sovereign decisions without his approval. Siddhartha warned, "If we go to war, King Pasenadi will further curtail our autonomy."

The enraged Senapati declared, "Your cleverness won't save you. You must obey the Sangh's majority decision. Don't think the Kosal King's permission is needed for us to punish you. The Sangh can socially boycott your family, sentence you to death or exile, and confiscate your family's property."

Siddhartha realised the consequences of defiance. He had three choices-- join the war, accept the death penalty, or go into exile and risk his family's ruin. The first was against his principles. The second, he saw it preferable to bring hardship to his loved ones. So he said, "Please do not punish my family for my cause. Let me bear the consequences alone. I willingly accept either exile or death. I promise not to appeal to King Pasenadi."

But the Senapati replied, "That is not feasible. Whether you accept exile or death, the Kosal King will know. And he may see it as a punishment by the Sangh and take action against us."

Siddhartha said, "Then I shall become a parivrajak (wandering ascetic) and leave this country. That too is a form of exile."

The Senapati accepted this solution. Siddhartha promised to seek his family's consent but vowed to leave regardless of their consent. Everyone trusted his word. Still, if Siddhartha went at the same time war was declared, King Pasenadi would surely learn of the internal conflict. To prevent suspicion that his departure was related to the war, a young Shakya proposed delaying the declaration of war until Siddhartha would leave. The Sangh accepted the proposal, and the war was postponed.

Before Siddhartha could reach home, his family had already learnt of Shakya Sangh's decision. His parents were submerged in sorrow. King Shuddhodan's father said, "We never imagined you would make such a decision."

"Father", replied Siddhartha, "I hadn't anticipated things going this far either. I truly believed my reasoning would win over the Shakyas and dissuade them from war. But our Senapati and military leaders had already deeply washed the people's brains, and my arguments held no weight. Still, I hope you understand that I did not abandon truth and justice, though punishment was inevitable. I at least succeeded in bearing the burden of punishment myself."

"But did you not think of what would happen to our family?"

"That is exactly why I chose the path of renunciation. Just imagine if the Sangh had decided to seize our property and land—what would have become of us then?"

"What meaning does this land and property hold without you?" asked Shuddhodan.

Sobbing, his mother, Prajapati Gautami, proposed that the entire family go into exile or seek refuge with the King of Kosal.

"That wouldn't be right, Mother," Siddhartha said. "The Shakyas would see that as a betrayal. I have promised never to let the King of Kosal learn of my renunciation. I will indeed be alone in the forest. But being alone in the forest is far better than being complicit in the slaughter of Koliyas, Mother."

"The Shakya Sangh has postponed the war for now," Shuddhodan said. "Could you not postpone your pravrajya as well?"

"My proposed pravrajya is precisely the reason the war has been delayed. This may lead to a full withdrawal of the war declaration. But that depends entirely on my renunciation. If I break my vow, it could gravely harm the peace of our people and land. Please, don't stand in my way. Instead, bless my journey."

Eventually, Siddhartha went to see his wife, Yashodhara, who had just given birth to their son, Rahul. What was he to say? How would he say it? He stood there, silent. To his surprise, Yashodhara, full of grace, expressed moral support for his decision and wished him well in seeking the greater good of humanity. Finally, Siddhartha gazed lovingly at his infant son and bid them farewell.

Siddhartha wished to formally take renunciation (pravrajya) at the ashram of Bharadwaj, located in Kapilavastu. At dawn the next day, he mounted his beloved horse Kanthak and, accompanied by his attendant Channa, headed to the ashram. A crowd had already gathered at the gate. He had hoped his parents wouldn't witness his pravrajya, but both had arrived quietly. Siddhartha struggled to tear himself away from their embrace.

He removed his royal clothes and ornaments and handed them to Channa. He got his head shaved. Wearing the yellow robe brought by his cousin Mahanam and carrying a begging bowl, he went to Bharadwaj to take the vows of pravrajya.

By his vow to the Sangh, Siddhartha immediately left Kapilavastu after his pravrajya and headed towards the Anoma River. A crowd followed. He turned to them and said, "My dear, it is useless for you to follow me. Please, return. I failed to resolve the conflict between the Shakyas and Koliyas. Perhaps you will succeed; please try."

Hearing his appeal, King Shuddhodan, Gautami, and the crowd turned back. Overwhelmed with sorrow at the sight of his discarded clothes and jewellery, Gautami threw them into a nearby lotus pond.

Guide

Siddhartha walked four hundred miles and reached Rajagriha, the capital of the Magadh Kingdom. There, he built a simple hut of branches. King Bimbisar of Magadh came to persuade him to return home. Bimbisar, a historical figure, was the son of the great Maurya King Chandragupta. Siddhartha, however, enlightened him and turned him back.

One day, five other renunciants arrived and built a hut alongside Siddhartha's. They were Kaudinya, Ashwaji, Kashyap, Mahanam, and Bhaddiya. They asked, "Don't you know what happened after you left Kapilavastu?" Siddhartha said he did not.

According to them, a massive anti-war movement erupted in Shakya state after Siddhartha departed. People of all ages and walks of life began daily demonstrations in opposition to war, in full support of Siddhartha's ideas. The Shakya Sangh was forced to convene. A majority now stood in favour of a peace treaty with the Koliyas. Five representatives were chosen for peace negotiations. The Koliyas also appointed five members. The talks succeeded, and a permanent council was established to resolve future disputes. The threat of war was eliminated.

Siddhartha could have returned at this point. The immediate cause of his renunciation had been resolved. But he thought deeply, "This was only one part of a much bigger problem. There is conflict everywhere. I will not return until I find the solution to this greater issue."

After seven years of renunciation, he attained sambodhi (enlightenment) in Bodh Gaya, now in Bihar, India.

Buddha's actions and teachings were radical rejections of ritualism, divinity, and the status quo. But his rebellion was never anarchic. Some so-called "brave" Kshatriyas called him a coward for refusing to go to war. But when he stood willing to accept the death penalty for his beliefs, their taunts ceased. Cowardice and nonviolence are not the same. Buddha was courageous in the truest sense. He had proven his valour by defeating others in archery to win Yashodhara's hand in marriage.

Nonviolence, to him, was a different and far superior form of courage. Attempting to transform a terrifying bandit like Angulimal took nothing short of extraordinary bravery. Emphasising this point, Mahatma Gandhi once said, "If I must choose between cowardice and violence, I choose violence."

Some accuse Siddhartha of abandoning his beautiful wife and newborn son. But Ambedkar's interpretation completely refutes this claim. The truth is, Buddha was the founder of a profound philosophical tradition and one of the greatest human beings the world has ever known. Yet, he had no ego.

Unlike religious icons such as Krishna, Muhammad, or Christ, he never claimed to be a rescuer. "I am not a deliverer," he used to say. "I am merely a guide. My teachings are not the ultimate truth; they are the best path I have perceived at this moment with my insight. If you meditate your best and experience in depth, you may find a better path."

(Author Shrestha is keenly interested in Buddhist literature.)

-square-thumb.jpg)