- Monday, 16 February 2026

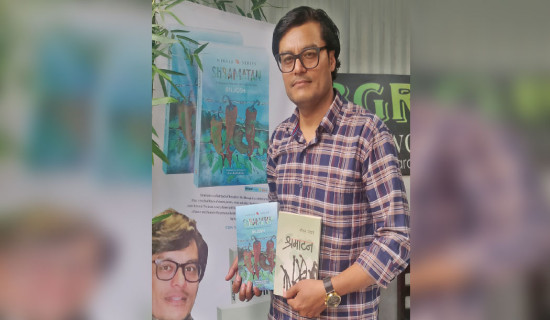

Gauchan explores Madhesi aesthetics in 'Keti Haraeko Suchana'

Kathmandu, Feb. 7: Deependra Gauchan’s new film 'Missing: Keti Harayeko Suchana ' makes a beautiful depiction of Madhesi community. It is done by someone who is from the hill community. Essentially, this film seeks to change the stereotype of the Madhesi community made by the hill and capital-dwelling elites. Another important thing is that, for the first time in the history of Nepali cinema, it does justice to the unspoken voice of the Madhesi heart. To portray this, Gauchan uses the subtle love story between a wealthy Madhesi man and a middle-class woman from the hill community.

The Madhesi people are the true protectors of Nepal’s southern borders. In the government's absence, no other community has suffered the hardships and oppression of the borderlands as they have. Yet, the community from the hill perceives them as Indian citizens or as being pro-India. This is an extremely cruel attack on the dignity of the Madhesi people. When one group diminishes another’s sense of identity, it is an assault on human civilisation itself. Even more problematic is when citizens of the same country question the nationality of a particular community—this is a form of communal intolerance. The Madhes movements of 2007 and others were fundamentally against this very problem.

In the film, Rambaran kidnaps Sita and takes her to Janakpur, just to show his friends the romantic photograph of 'his girlfriend' who is from the hill community. As their conversations progress, a sense of warmth gradually develops between the kidnapper and the kidnapped. Sita, in turn, orders Rambaran to take her on a train ride and take her for a Madhes visit.

There are numerous interesting dialogues between Sita, played by Srishti Shrestha, and Rambaran, played by Najir Hussain, which highlight the mindset of the people from the hill which commonly referred to as Pahade community and its resistance from the Madhesi people. In one scene, when Sita suggests that Rambaran should play the role of a dark-skinned character, he retorts, "Does being dark automatically mean being Madhesi? What kind of racist mindset is yours?"

To this, Sita justifies her statement, saying, "Being dark is not a bad thing. In fact, I find it charming—like Denzel Washington or Lord Krishna."

In another context, when Sita refers to a Madhesi man as "bhaiya," Rambaran immediately objects. "Doesn't 'bhaiya' mean elder brother?" Sita asks.

"Yes, but here, the connotation matters more than the literal meaning. 'Bhaiya' is used to label us as Indian citizens. The Madhes movement was precisely against such discrimination."

Rambaran argues that Madhesis were marginalised due to the discriminatory rule of the state. In contrast, Sita attributes their marginalisation to a lack of education. At this juncture, director Gauchan seems to be a silent judge, yet the scales tip slightly in Ram’s side.

This film although aims to change the narrative about Madhes, it does not depict a wholesome picture of Madhesi society. Instead, it tells a story of its beauty.

The film captures the breathtaking flat landscapes, vast mango orchards, trains, the sun rising and setting in a way that resembles emerging from or sinking into the sea, village ponds where buffaloes and people swim together, children herding on the back of buffaloes, dusty roads, and canals flowing alongside them. These are the scenic marvels of the Madhes.

In the Mithila region, nearly every household has women who create unique Mithila paintings—these are the unknown artists of the land. Rambaran introduces Sita to these sights and traditions, and she embraces them wholeheartedly. Through Sita’s perspective, the film sends a profound message—Madhes' beauty is acknowledged and accepted by the hill.

Much like in Italian neorealist films, in this movie, the Madhesi people are not only portrayed by Madhesi actors but they also contribute behind the scenes—as musicians, art directors and crew members. This strengthens the film’s depiction of Madhesi society. Certain scenes are notably long, such as the conversation between Sita and Rambaran inside Rambaran's haweli (palace) or their all-night romantic chat atop a haystack under the moonlight. Despite being lengthy, these scenes remain engaging. Both Srishti and Najir have delivered outstanding performances. However, the film has its shortcomings. First of all, the title is not creative. While it flows smoothly as a simple narrative, it suddenly turns into a thriller towards the end. Perhaps the director felt the need to add dramatic for commercial cause. Additionally, Sita’s frequently shifting moods reinforce the stereotype that women are unpredictable and difficult to understand.

While the film highlights the beauty of the Madhesi people, it overlooks the true sense of women. Sita is not just a person from the hill—she is also a woman. Even in love, men impose various injustices upon women.

In the final scene, when Sita visits Rambaran in jail, they engage in a romantic conversation, during which Rambaran says, "I want a small home, a big garden, and my wife to give birth to many children—at least five or six."

Sita does not verbally respond, but her facial expression suggests silent agreement. However, she could have replied differently, "I cannot bear many children just for my husband’s sake. But if there is true love, then perhaps even five or six children will not be a burden to me."

Clearly, women do not easily open the doors to love, but when they do, there will be no restrictions.