- Tuesday, 30 December 2025

A Veteran Scholar's Diary Of Momentous Era

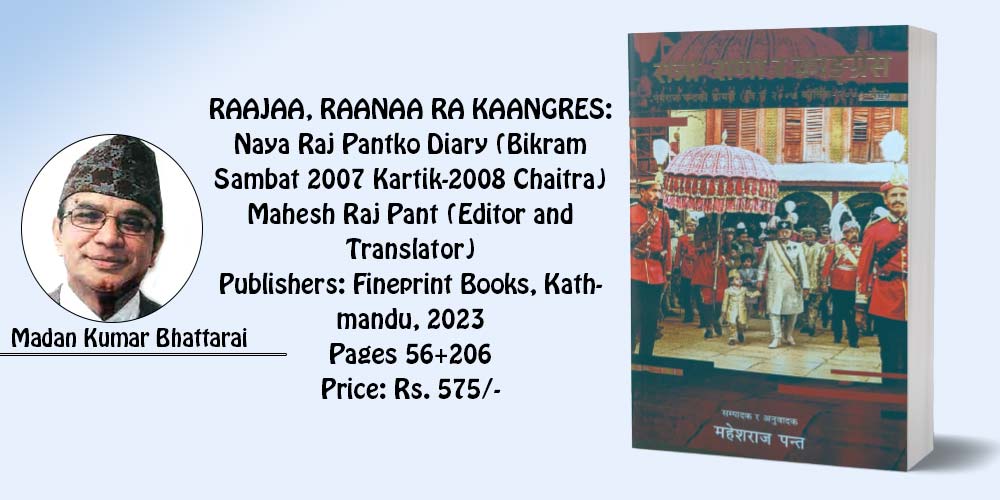

Mahesh Raj Pant, a noted scholar, prolific writer, and brilliant literary explorer in his own right, has done a commendable act in getting a portion of the diary of his illustrious father and one of the iconic academic scholars in the fields of Sanskrit, astrology, archaeology, history, and mathematics, Naya Raj Pant, duly translated and edited in the form of a book.

The wonderfully compiled work entitled RAAJAA, RAANAA RA KAANGRES: Naya Raj Pantko Diary (Bikram Sambat 2007 Kartik-2008 Chaitra) can roughly be translated as the King, Rana, and Congress: Diary of Naya Raj Pant (From November 1950 to April 1951). The book has an impressively colourful cover depicting the arrival of three-year old smart-looking "King," Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, escorted by the last Rana Prime Minister Shri Teen Maharaj Mohan Shumshere to formally accept the Nepali Crown in the absence of his grandfather, King Tribhuvan, who opted to take political asylum in the premises of the Indian Embassy in Kathmandu a day earlier.

It has a long prologue that is not only self-revealing but also a succint summary of the diary in such a way that it has shed light on the painstaking endeavour of the diary keeper and the context he has referred to. It also contains two pages of a diary in handwritten form as a draft and clean copy made by another scholar, historian, and explorer, Gyan Mani Nepal, who sadly passed away recently.

The second part of the book contains original Sanskrit entries both in prose and poetic format in the form of a diary so meticulously kept by veteran scholar Naya Raj Pant that runs for a length of hundred pages, becoming the biggest chunk of the publication. The late Pant is known for his frank and straight-forward style and followed an approach to call a spade a spade.

Pages 101 to 110 are highly readable in the sense that these translated entries in the diary not only speak of the flight of the monarch to the Indian mission on November 6, 1950, but also provide an eyewitness account of the subsequent decision by Rana Regime to "dethrone" the King and install a child on the throne the following day. They also portray a sense of despondency pervading the Rana rulers with a despotic background of more than a century.

However, Naya Raj Pant seems more inclined to blame Prime Ministers for the last six and a half decades of the regime, starting with Bir Shumshere possibly trying to absolve Jang Bahadur, who was in power for the longest period in the Rana period and second longest stint in Nepal's history, Ranoddip Singh, who was murdered by his own family members, and a small interregnum by Bam Bahadur.

Likewise, the entries from pages 111 to 115 are significant in the sense that they expose King Rajendra for not being committed to the task set out by King Prithvi Narayan Shah and his sheer inability to rule, giving Jang Bahadur an opportunity to craft a regime for himself and his family that lasted a century. They also portray duplicity of purpose on the part of Rana members who were out of roll of succession in the post-1951 era.

This portion most prominently talks of what can be called double standards on the part of Balakrishna Shumshere (later Balakrishna Sama). The veteran scholar is depicted more as an opportunist taking his role in the death of Laxmi Nandan Chalise in jail, his signature in the resolution calling for King Tribhuvan's ouster, his presence along with his son as photographers during the installation of "King" Gyanendra earlier, and allegedly courting favour from Nepali Congress for his own interest. It also questions intentions on the part of India for its deeper involvement in Nepal's internal affairs.

Similarly, some other entries of the diary are associated with Pant's critical assessment of people and events. He lays bare many veterans from bureaucracy, the army, and even politics, talking of what can be called their sheer opportunism to serve their own petty interests at the cost of a larger national interest.

The third part, consisting of 88 pages, is a Nepali translation of the original Sanskrit text that makes the book easily comprehensible to most of the readers. The remaining section deals with appendices, a bibliography, and a list of individuals mentioned in the most comprehensive diary.

While there is a mention of many people relating to Nepal's diplomacy and international relations, one interesting aspect is on page 180 that speaks of the chronicler's sarcastic analysis of the wedding of Khadga Man Singh Basnyat, who spent twenty years in jail during the Rana period and was foreign minister (Counsellor for Foreign Affairs) at that time.

Besides coming from the pen of the renowned scholar with multi-disciplinary knowledge and expertise, imbued with a spartan way of life, this particular portion of the diary can be taken as a tribute to the reputed chronicler for scrupulous recording one of the most defining periods of Nepal's political and social history.

Even in going along with the current narrative of using rather popularly fashionable word, transition, inconceivably all aspects of happenings, this period of Naya Raj Pant's diary pertains to possibly the most defining era of the biggest transition in Nepali history.

This book can serve as a substantive base for anyone involved in the research pertaining to the period, as it is a treasure house of information from one of the most dedicated and enlightened scholars. One major takeaway of the book is that most of the people who matter in Nepal tend to court political people irrespective of their affiliations or past associations for their own interest.

In a nutshell, Mahesh Raj Pant's initiative can be taken as the most welcome step in enlightening not only academics, research scholars, and students but also general people about Naya Raj Pant's brilliant perceptions and analyses of the people and events of the most eventful period of the early fifties.

But there will be a natural request on the part of all to urge him to come out with publications of other portions of the diary of the veteran scholar in the near future. I congratulate Mahesh Raj Pant on his wonderful work.

(Bhattarai is a former Foreign Secretary, ambassador, and author. kutniti@gmail.com.)

-original-thumb.jpg)