- Sunday, 22 February 2026

On Managing Forests

Forests are not 'jungles' anymore - they are the crops that can be cultivated. They are regenerated or planted, grown, harvested, used, and again regenerated in perpetuity. Nowhere is the concept of 'sustainability' more relevant than in forests when they are sustainably managed or cultivated.

Notwithstanding, it is widely accepted that Nepal's forest resources are under-utilized or under-managed compared to their full potential.

Conservation is institutionalized, by and large, thanks to government institutions and more than 30,000 community groups around national forests across the country. Recent statistics on the national forest assessment estimate that both the area and the stock of forests are increasing.

The forest area that was well below 40 percent of the country's area before the year 2000 is now around 45 percent. Not only politicians but also techno-bureaucrats and researchers alike argue that the forestry sector should significantly contribute to the country's economic prosperity since conservation is institutionalized.

It is in this logic that the forestry sector has been recognized as one of the 'economic sectors in the 15th Periodic Plan (2019/20-2023/24). This 'economic way of thinking for the forestry sector is not baseless---it is well founded on several knowledge products and scientific data.

A report entitled 'Nepal Environment Sector Diagnostic: Path to Sustainable Growth Under Federalism' produced by the World Bank Group in 2019, for instance, calculates that nearly 2 million hectares of community-based forests in Nepal can yield up to 2.89 million cubic meters of timber per year compared to only 0.96 million cubic meters at the current base level.

The monetary equivalent, the rent, of the 2.89 million cubic meters would be US$ 455.90 million in addition to government taxes and royalties compared to only US$ 68.96 million currently.

The Nepali equivalent at the rate of NRs 125 per US$ is enormous, totaling almost 57 billion Nepalese rupees per year as forest rent besides additional approximately 21 billion Nepalese rupees as taxes, royalties, and VATs.

The total royalties, taxes, and VAT from the sale of timber and NTFPs is currently only around 900 million Nepalese rupees. It shows how much the forestry sector can contribute to national prosperity only from logs, let alone the values of other products and services from the sector such as medicinal herbs, carbon, bio-energy, and nature-based tourism.

However, between the full potential and its actualization lies a black box, which is nothing but the ways forests should be managed.

Realizing the potential in forestry is not impossible provided there are proper policy interventions and appropriate management actions.

The National Forest Policy of 2019 has already guided the sustainable harvest of Nepal's forest resources to its full potential. What the forestry sector in Nepal needed was a practical guidebook for sustainable forest management based on empirical evidence and a robust theoretical foundation.

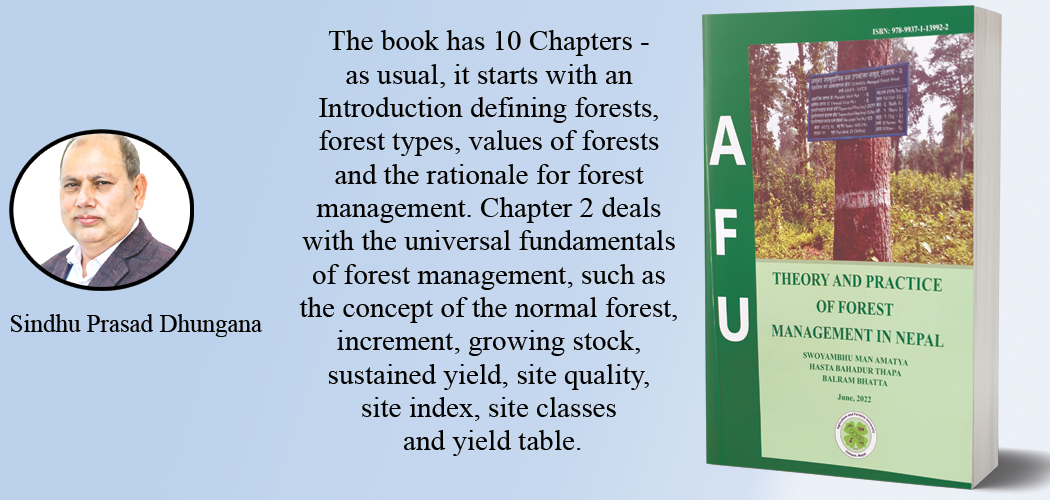

Last month, as a surprise to policymakers, foresters, researchers, and forest management practitioners, a silver bullet appeared in a book entitled 'Theory and Practice of Forest Management in Nepal 2022'.

It was a magical solution to the challenges faced by Nepalese forestry actors, who were desperate to venture into forest management but did not know properly how to. The book is published by the Faculty of Forestry under Agriculture and Forestry University.

This is a co-production of the author trio, Dr. Swoyambhu Man Amatya, Hasta Bahadur Thapa, and Prof Balaram Bhatta. Dr. Amatya, the lead author and copyright holder, is a well-versed researcher, economist, administrator, and academician with a long career ranging from forest officer through the Secretary of the Government of Nepal to currently an Adjunct Professor.

Despite his career in government bureaucracy, his contribution to the knowledge system particularly in the management and economic aspect of forestry is widespread in several forms including books, journal articles, and published reports from which a large number of readers and researchers have benefitted.

Thapa is also a forestry expert, who spent more than three decades in forestry action research and measured forest management plots for knowledge dissemination. Prof Bhatta encounters forestry students and researchers at Bachelor's, Master's, and Ph.D.

levels every day and guides them in the theory and practice of forest management for which he chose the right direction to co-author this book.

The book has 10 Chapters - as usual, it starts with an Introduction defining forests, forest types, values of forests, and the rationale for forest management. Chapter 2 deals with the universal fundamentals of forest management, such as the concept of the normal forest, increment, growing stock, sustained yield, site quality, site index, site classes, and yield table.

This chapter is particularly helpful for those who are interested in the theoretical aspect of forest management. Chapter 3 focuses on how forest resources have been managed in Nepal historically and can be exciting to those who are nostalgic for the past.

Chapter 4 reflects the concept of silviculture systems---the backbone of sustainable forest management and sustained yield, whereas Chapter 5 highlights how silviculture systems have been applied in Nepal albeit at a token scale. Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8 describe tree rotation, yield regulation, and tending operations respectively, which are the basic ingredients of forest management. Chapter 9 introduces the concept of 'Forest Certification, which is a formal international practice to certify whether the forest patch in question is sustainably managed.

Despite the high relevance and overall perfection of the book, there are some areas where the authors could have been mindful. The book overly emphasizes the 'technical aspect' of forest management, whereas sustainable forest management is not complete without integrating it with socio-cultural, political, economic, and biophysical or ecological contexts.

Consequently, the book has been 'timber-centric' and 'apolitical', which is true to our need to harness the full potential of producing 2.89 million cubic meters of timber sustainably per year, but can we produce this much volume without proper considerations of environmental and socio-cultural safeguards and readiness? Perhaps, that part was beyond the scope of this book since a single publication cannot cover everything we want.

Readers should not be looking for the overall 'ecosystem goods and services from forests relying only on a single book that is meant to fulfill a gap of 'under-utilization' of forests in terms of timber potential.

We should appreciate the authors for their honesty to admit that it is a book on 'forest management' without any qualifiers such as 'sustainable' or 'scientific'. Overall, this paperback is a must-read and use guidebook if you want to green-wash your mind to understand and realize 'Hariyoban Nepalko Dhan' (Green forests are Nepal's wealth).

(Joint Secretary at the Ministry of Forests and Environment, Dhungana holds a PhD)

How did you feel after reading this news?

-original-thumb.jpg)