- Thursday, 12 March 2026

Enhancing Urban Mobility And Safety

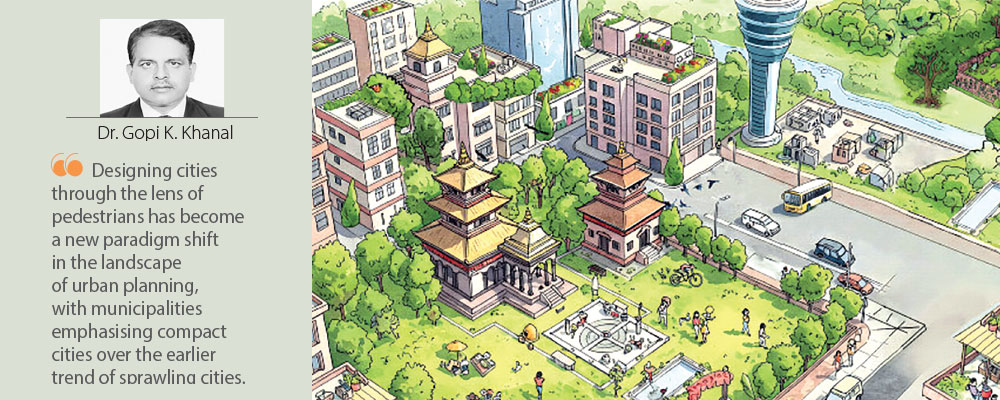

Comfortable urban mobility has been the central concern of urban planning and design. City governments around the world are investing resources in redesigning public spaces with pedestrian-friendly infrastructure. Given the growing pace of urbanisation, promoting walkable cities has become necessary to mitigate climate change risks, address public health concerns, promote urban economic growth, and improve the quality of life.

Designing cities through the lens of pedestrians has become a new paradigm shift in the landscape of urban planning, with municipalities emphasising compact cities over the earlier trend of sprawling cities. The compact city movement has prompted the city planner, urban economist, and policymaker to create the urban built environment in such a way that people are motivated to walk or take the cycle to move around the city for jobs, entertainment, and other purposes. The pace of urban mobility and its outcomes are directly linked to the structure and quality of the urban built environment, such as buildings, street layout, safety, urban beautification, street lights, public amenities, sidewalks, physical infrastructure, availability of public services, businesses, and many others.

Spatial constraints

Many factors have prompted the city governments to put pedestrian comforts at the top of their urban policy radars. The main reasons behind this transformation are decarbonisation and the urgent need to address climate change, public health concerns, spatial constraints to growth, and concerns of urban economic development. Vehicle movements in the cities are the sources of air pollution. They emit carbon dioxide (CO₂)—one of the main contributors to greenhouse gases. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), travel by car roughly emits seven times more CO₂ per passenger-kilometre than travel by urban rail. Walking and cycling are the most climate-friendly ways of urban travel with the lowest environmental footprints.

The way cities are designed has implications for carbon footprints and pollution levels. It is found that the denser a city is, the lower its transportation-related emissions. A climate-resilient city encourages citizens to walk and cycle rather than rely on private cars. In denser cities, people generally consume less energy at home compared to those living in urban sprawl. In sprawling cities, houses tend to have larger rooms and more floor space, which requires higher electricity consumption for lighting, heating, and cooling. By contrast, in dense urban environments, people often live in compact and shared structures, which contribute to energy efficiency. Making cities denser and more compact increases the likelihood of walking and cycling, which will help to reduce energy consumption and mitigate climate impacts.

Making cities walkable contributes significantly to addressing public health concerns. Walking and cycling are highly beneficial for preventive health and promoting overall physical well-being. Reducing car use can also help lower human deaths and injuries from traffic crashes. Fewer cars on the road reduce respiratory and other diseases related to physical inactivity and air pollution. The lack of sufficient physical mobility has become one of the major concerns of public health worldwide. Studies have found that body mass index (BMI) tends to be lower in walkable cities than in cities where people primarily travel by car. Many countries have adopted mobility improvement as a key public policy instrument to enhance public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on vehicular movement led to a sharp reduction in air pollution in the Kathmandu Valley.

Prioritising pedestrians and other sustainable modes of transportation can help address problems arising from the spatial and geographical constraints of urban growth. Land is always scarce in cities, and allocating excessive space to private cars reduces public space, including areas for walking and cycling. Sidewalks can move far more people per hour per kilometre than traffic lanes dedicated to private vehicles. Research has shown that within a 9–10-foot traffic lane, space allocated to pedestrians can move approximately 10,000 people per hour. If the same lane is dedicated to buses, it can carry around 6,000 people per hour, whereas if it is used for private cars, it can move only 1,000-2,000 people per hour. If it's used for light rail corridors, we can move about 11,000 people per hour per direction.

Converting urban space for pedestrians generates significant economic benefits. It has been observed that cities ranking high on liveability indices, such as Melbourne, Vienna, Vancouver, Toronto, and others, have allocated more space for walking with high-quality public open spaces. Even in Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur, most economic and service-related activities take place in areas with high pedestrian movement. Evidence shows that people tend to purchase more goods and services when moving on foot compared to travelling by car or bus. Pedestrian-friendly cities encourage the night-time economy that will create jobs for youth with new business opportunities.

Creating a walkable city requires a multi-pronged strategy. People prefer to walk when walking is useful, safe, interesting, and comfortable. Walking becomes useful when the essential needs of daily life, such as shops, services, workplaces, and public facilities, are located along walking routes. People feel safe to walk when there are no security risks and minimal chances of traffic accidents. The route of walking should be interesting, offering visual appeal that encourages people to walk simply by seeing the surroundings. Areas such as Patan and Bhaktapur Durbar Squares demonstrate how historic urban environments naturally attract pedestrians. Walking routes should be comfortable for all groups of people, including children, older persons, and persons with disabilities.

Several initiatives

Municipalities in Nepal have taken several initiatives to improve urban mobility. Compared to the past, Nepali cities are now relatively cleaner and greener. The street lighting programme introduced by the former Ministry of Local Development was very effective in enhancing urban mobility and safety, particularly during evening and night hours. Many cities have recently installed high-mast lighting systems in city centres, which encourage city dwellers to move more freely and confidently. Street lighting is an integral component of a walkable city. Planned cities are more attractive for urban mobility than unplanned ones. Lalitpur Metropolitan City has developed cycle lanes. Roadside greening initiatives undertaken by Kathmandu Metropolitan City, particularly during the SAARC Summit, have enhanced the walking environment.

The municipalities in Nepal should adopt the 15-minute city concept, where residents can access most essential services within a 15-minute walk or cycle from their homes. Environment-friendly local governance initiatives implemented in cities such as Bharatpur, Dharan, Dhangadi and many others have significantly contributed to improving urban mobility. The municipality should promote the car-free zone time limit, which is beneficial both for the night-time economy and urban mobility. The Ministry of Urban Development should prepare a national programme to support municipalities in developing pedestrian-centric cities. UN-Habitat Nepal should support bringing international know-how on improving urban mobility through the compact city initiative. Improved urban mobility should be one of the top priorities of urban policy and programmes in Nepal.

(The author is the former secretary of the Nepal government.)

-square-thumb.jpg)

-original-thumb.jpg)