- Thursday, 19 February 2026

Misinformation Fuels Social Unrest

On the first day of the Gen Z protest on 8 September, rumours spread on social media that over 35 skeletons had been discovered at the Bhatbhateni Superstore in Chucchepati, Kathmandu. Later, however, only six bodies were actually recovered.

The next day, another hearsay went the rounds that 32 missing protesters had been found dead inside the Parliament building in New Baneshwor. Although the Nepal Police confirmed these stories were baseless, social media influencers and public figures such as Tanka Dahal, Sujan Dhakal, Shiva Pariyar, Himesh Panta and Bhagya Neupane went on to disseminate false information.

A video of an air hostess claiming that Nepali Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli was spotted fleeing the country to an unknown destination via Dubai on 10 September went viral. She said Oli was being carried in a wheelchair by her colleague under the security of the authorities in Dubai. She even expressed her helplessness for not being able to do anything and urged others to help, calling on Nepalis in Dubai to reach the airport. This video was shared by hundreds of thousands of people on various social media platforms.

The posting of this video coincided with rumours since September 9 that then PM Oli was fleeing the country on the pretext of medical treatment in the wake of the Gen Z uprising in which 19 youths were killed on its first day. Himalaya Airlines – a Chinese and Nepali joint venture – was linked with the rumours. The company stated that its serious attention had been drawn to online reports, citing unnamed sources that PM Oli was preparing to fly on a Himalaya Airlines aircraft for medical treatment abroad.

Fake news flies fast

However, online media continued to carry the news, forcing the airline to issue another press note the next day, saying the report was “completely false and misleading.” “Despite yesterday’s press note, we have come across various media channels reporting the news of Mr KP Sharma Oli flown or flying to Dubai on Himalaya Airlines. We would like to reiterate that this news is completely false and misleading. We sincerely request everyone not to believe or disseminate such unverified information,” read the note.

Likewise, another video went viral showing a man – allegedly identified as Nepali Congress general secretary Gagan Thapa – being dragged along and kicked by a mob. Similarly, another featured a man – allegedly the then Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Bishnu Prasad Paudel – running in a river to save himself from protesters, only to be pursued and beaten. Videos purporting to show other leaders, such as Mahesh Basnet, also went viral.

As seen in many countries around the world – with Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Indonesia being the latest – Nepal’s recent protests provided fertile ground for spreading misinformation and disinformation. Social media sites, especially Facebook, TikTok and X, were flooded with videos containing fake information, while some users deliberately sought to misinform the masses.

With more than three-quarters of the population having smartphones, and most accessing the internet via broadband or GPRS, the impact of social media has risen like never before. Sadly, some of the popular legacy media outlets have stooped to competing with social media, creating another challenge in protecting the essence of journalism, which is under severe threat from the rise of influencers and content creators.

One example is the YouTube channel Tough Talk, operated by Dil Bhushan Pathak, former editor of Kantipur Television. In one presentation, Pathak claimed that Jaybir Deuba, son of Nepali Congress president Sher Bahadur Deuba, had bought the international hotel chain Hilton. He linked the issue to corrupt political leaders, including Deuba and his wife, Arzu Rana Deuba, then Foreign Minister. But most of his presentation was based on assumptions and hearsay. The only fact he substantiated was the denial of a share purchase between the hotel owners and Jaybir.

Clips of Pathak explaining how corrupt money was being channelled into business expansion by politicians’ children went viral. While the issue had already been raised by some YouTube channels, Pathak’s credibility further pushed the misinformation to the masses.

Increased access to smartphones,

According to a survey by the National Statistics Office (NSO) in March 2024, about 76 per cent of Nepali households own smartphones, with 4.9 million families having at least one device. This figure is higher than in neighbouring India and Bangladesh, where smartphone use is slightly above 50 per cent.

In Nepal, those aged 25–35 make up over half of all smartphone users. Social media use has also reached a significant milestone, with 50 per cent of the population (about 15 million) using Facebook and YouTube. Both platforms require minimal technical skills and English, making them popular even among the elderly and rural population. Other widely used social media channels include Instagram and X.

The protests and the flood of fake information coincided with Meta – the parent company of Facebook – monetising the application, allowing users to earn from reels. “There are people who unknowingly fall victim to fake information, while others enjoy it knowingly. And influencers are running after the cents, willing to say anything that will bring them more dollars,” said journalist and fact-checker Deepak Adhikari.

Umesh Shrestha, known as Shalokya, a fact-checker and one of Nepal’s first bloggers who still runs mysansar.com, said misinformation was rife in earlier movements, COVID-19 and elections, but this time it was more noticeable. “The monetisation of Facebook motivated more people to make misinformation viral. Since this happened when mass media and journalists’ credibility is dwindling, it inflicted greater damage,” he said.

Shrestha noted that misinformation such as claims that the Nepali Army was preparing a coup, or that Narayanhiti Palace Museum was being cleaned to welcome the dethroned king, preyed on public fears. Other claims, such as 32 bodies found inside Parliament, incited the youth to further violence. Even platforms with small user bases in Nepal, like Telegram, carried false claims.

Social media: Source of misinformation

A research report by Ujjwal Acharya and Chetana Kunwar, published in Nepal’s Misinformation Landscape (Centre for Media Research, 2024), found that political and social issues make up almost 75 per cent of misinformation topics in Nepal.

Analysis of 414 fact-checked items showed that 76.17 per cent of misinformation originated from media or social media authors, while politicians accounted for 17.69 per cent. By platform, 56.5 per cent spread via social media, 19 per cent via mainstream media and 17 per cent via online portals. These findings challenge the commonly held notion that the legacy or mainstream media perform fact-checking seriously and that the journalistic process ensures that only accurate information is transmitted. As many scholars and media experts suggest, credibility is probably the best asset that will help the traditional media as well as online news channels amidst the information blizzards created by social media.

Another report in the same book, based on a survey of 3,448 adolescents conducted by Kunwar and Ujjwal Prajapati over 2023–24, found that 58 per cent admitted sharing unverified information, with 20 per cent doing so frequently. About 68 per cent encountered misinformation on social media, 38 per cent on online news sites, 25 per cent by word of mouth, 19 per cent on television, 13 per cent in newspapers and 10 per cent on radio.

Influencers, particularly celebrities, were the most responsible for spreading misinformation, according to 40 per cent of respondents. About 25 per cent blamed social media users, while others identified journalists, media workers and politicians. The researchers found that 60 per cent had never heard of media and information literacy. This demands an urgent action from the government, academia, civil society and media channels, including the social media operators, to design and implement Media and Information Literacy (MIL) programmes for various categories of masses, from those who are native to the new media and those who migrated to it recently.

However, there have been only a few efforts to implement MIL programmes, especially by the non-government organisations like the CMR. The institutions like the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, the Department of Information and Broadcasting, and press registrar offices at the provincial level could have designed and organised such initiatives. But the results are not encouraging.

Fact-checkers were overwhelmed by the torrent of misinformation during and after the protests. At one point, world-renowned eye surgeon Dr Sanduk Ruit had to call a press conference to deny rumours he was joining a cabinet led by Sushila Karki. By the time fact-checkers complete their verification, the damage is often already done, with fake content spread beyond measure. Worse still, fact-checked corrections are largely ignored, even by educated audiences, said Shrestha.

Fact-checkers argue that media houses must maintain in-house verification teams. Even opinion articles and letters to the editor should be checked so that the historical record is not distorted. Ultimately, however, audiences themselves bear responsibility. With access to verified information from official sources, users can avoid being duped, at the very least by not sharing doubtful content instantly.

Often, people share information in close circles, from where it rapidly spreads outwards. “Do not send or share any information until you understand the whole context. Wait and verify. Even doubt the camerawork, because an alternative angle can change the entire meaning,” said Adhikari. He added that had people simply asked “where is Oli in the video?” they might not have spread the rumour of his escape.

Shrestha also maintains that users have the first responsibility to check misinformation, though government, media and educators also have crucial roles.

How to spot it

The increasingly professional use of AI tools and creators’ expertise is making fake news and deepfakes harder to detect. “As fact-checkers find new ways to identify it, propagators find new ways to improve their content,” said Adhikari. He advised paying attention to landmarks, geography, locality and natural features in videos or photos to verify authenticity, noting that many fake items are actually from other countries but passed off as Nepali events.

Checking and verifying the credibility of the source of information is the basic. Users should look for reputable and trusted sources or media outlets that have a good track record in terms of accuracy. Many media channels that claim to be neutral or non-partisan have their tilt to certain political parties or interest groups, even foreign countries or powers. This is rampant in the case of Nepal; audiences can find all these media in operation.

Users should avoid instantly reposting information. Instead, they should save and scrutinise it before sharing. Adhikari said many people also fall victim to confirmation bias – liking or sharing information that aligns with their existing beliefs. Comparing the information with other trusted sources, especially with the official documents, data or statements from the related authorities, not clicking the obscure sites, and checking timelines of the event can be instrumental in identifying fake information.

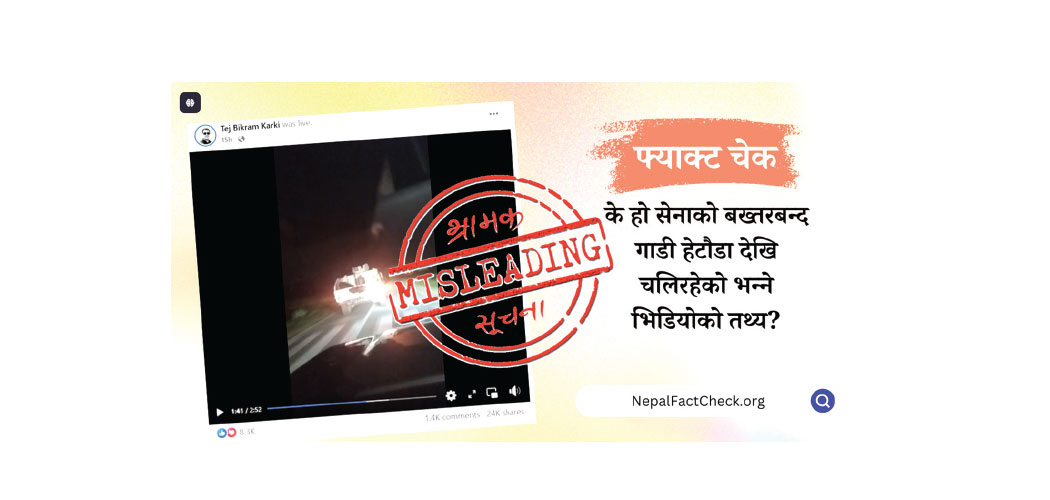

Likewise, fake information mostly uses sensational, emotional or indecent language while legitimate sources of information use a moderate tone and show a balanced attitude. There are high chances that highly viral information was verified by the fact-checkers, so one can visit their sites – such as nepalfactcheck.org, factcheck.org, and politifact.com.

(Dhakal is a journalist at this daily.)

-original-thumb.jpg)