- Wednesday, 4 March 2026

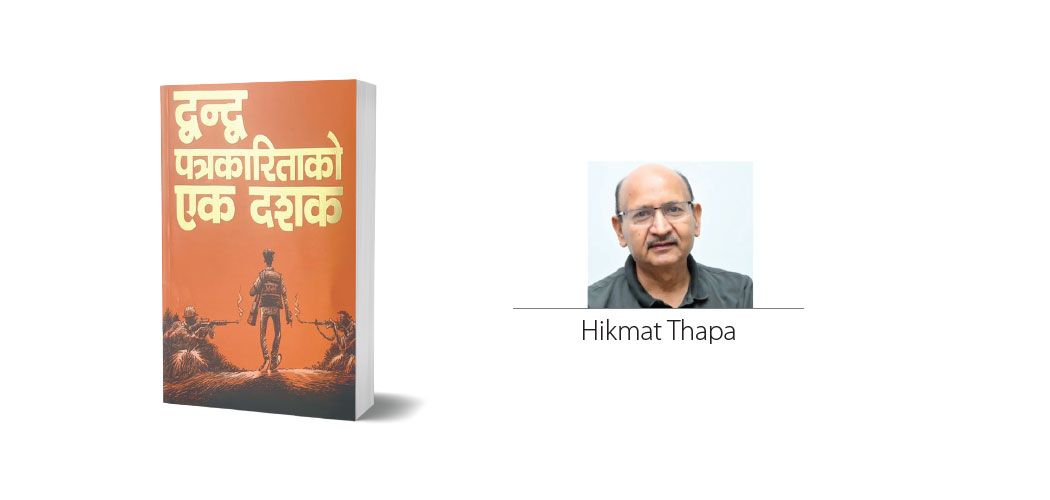

Journalist's War-torn Witness

In 1995, the then Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) launched an armed insurgency under the banner of the people's war. No one in the country remained untouched by this violent uprising. Seventeen years have passed since the comprehensive peace agreement signed between the seven political parties and the insurgents brought an end to the decade-long conflict. However, the pain and suffering caused by those ten years of conflict continue to haunt the people.

Our family was among the thousands of families who were forced to leave their homes during the Maoist insurgency. The memories of that day still make my skin crawl, and fear runs down my spine. On that day, an armed group of Maoists attacked our house in Katase, Kailali, intending to kill my father. They attacked our home while firing guns, but fortunately, they did not find him.

By coincidence, my father was in Tikapur that day. I was working in Chitwan at the time. They held guns to the throats of my brothers and looted our house, taking away my mother's jewellery, clothes, and important documents, but leaving behind books and other items. As they were leaving, they shouted that they would physically harm my father when they found him. That day was Mangsir 19, 2058 B.S. (2001 AD). It is likely that our house in the eastern part of Kailali was the first to be attacked in that region. My father was at that time a local leader of the Nepali Congress, a member of the District Development Committee, and the President of the largest community forest in the Karnali watershed area.

This book, Dwonda Patrakaritako Ek Dashak (A Decade of Conflict Journalism), by journalist Dirgha Raj Upadhyay, narrates similar tragic events like our own painful experience.

After the 2046 (1990 AD) People's Movement, the far-western region of Nepal began to dream of development and prosperity, separated from the rest of the country and Kathmandu. But how did this dream of development and prosperity for the far-western region fade away? The region, along with the rest of the country, was engulfed in a swamp of murder and violence, leading to untold suffering, torture, killings, and disappearances.

The book vividly details these tragic events, highlighting how attacks and violence from both the Maoists and the state took a heavy toll on society and citizens. Upadhyay’s narration skilfully allows the reader to feel the impact of the conflict on a personal level.

During his leadership role in the Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ), Kailali, the author, was directly involved in efforts to secure the safety and professional security of journalists. His personal experiences as a journalist in conflict zones reflect how the media and society coped with the violence and trauma.

The book also includes a list of journalists who suffered from killings, disappearances, and torture during the conflict period. It also discusses Upadhyay’s protective role in saving journalists from both Maoist and state forces. For instance, he played a crucial role in saving journalist Lucky Chaudhary, who was nearly killed by the Maoists, and also helped journalist Nagendra Prasad Upadhyay, who was abducted by the state. The book describes how Upadhyay took personal risks to ensure their safety and how far he went in his struggles. He also led a prolonged effort to bring justice and compensation to the family of journalist JP Joshi, who was murdered after being kidnapped from Attariya in Kailali.

Dr. Suresh Acharya, former president of the FNJ, said that Upadhyay’s experience is not just personal but also a history of journalism during that era. Former president of the FNJ, Taranath Dahal, mentions that this book is a picture not only of Nepali politics and journalism but also of the most difficult period in Nepali civilisation. During the harsh times of armed conflict and royal repression, Upadhyay held high the banner of press freedom in the far-western region, and the book bears the imprints of these struggles. He adds that every journalist must read this book to understand and learn from those challenging times.

As an active correspondent throughout the armed conflict, Upadhyay not only reported from his region but also from other areas, where he risked his life to report and, at times, to save the lives of fellow journalists caught in the crossfire. Former president of the FNJ, Bishnu Nishthuri, comments that this book is not only a personal memoir but also a valuable resource for new generations to understand the state of journalism during the conflict in Nepal.

Former president of the FNJ, Dharmendra Jha, notes that the book is not just a personal account but represents the collective experience of journalists during those years. It is a testament to the hardships faced by journalists and society, and future generations will learn much from this historical document.

Upadhyay recounts his experiences from covering the Maoists' first mass rally, as well as the many tragedies he witnessed and heard about from places like Pandoun, Banbeheda, Khimadi, Lamki, and Ghoda Ghodi. He also describes how, in Doti, the Nepalese army brutally killed civilians on suspicion of being Maoists and how the Maoists in Kanchanpur murdered civilians in retaliation. In a chapter titled "When Will There Be Justice?", the book details the gruesome killings of ordinary citizens by both the state and the insurgents across different parts of the country.

The book vividly depicts the pain and suffering of the people, from Rolpa to Surkhet, Achham, Doti, and Banke Bardiya. It is as if the journalist is narrating the story of a decade-long war where the poor were crushed and killed, and the remote villages and huts were left empty. The book also explores the deteriorating condition of the police, army, administration, and the general public’s unsafe status. Journalists themselves were caught in the middle of the conflict, often at the mercy of both warring parties.

The book also provides an in-depth description of the Maoist attack in Kailali. The author narrates his experiences during his travel from Dang to the far-western region, vividly portraying the impact of the war on the people and geography of Nepal.

Those ten years narrated by the book were the most tragic in Nepal's history. Being written by a journalist, it reflects the deep national suffering of the period. I felt the persistent fear, mental tension, and the unremitting bad news that all Nepalis had to endure.

The economic, social, and familial ravages we suffered are also reflected in the book. Each word evokes bitter memories, such as the tears of the people of Karnali—both purifying and sorrowful.

(The author is a former treasurer of the Non-Resident Nepali Association.)