- Friday, 20 February 2026

Burnt Walls, Unbroken Democratic Soul

Koirala Niwas (residence) in Biratnagar stands like a living document of Nepal’s democratic movement. This very house witnessed countless chapters of political upheavals, movements, exile, return, and ideological struggle. Over time, however, this legacy was scarred by family partition, physical encroachment, and eventually a violent incident. Today, it stands awaiting reconstruction.

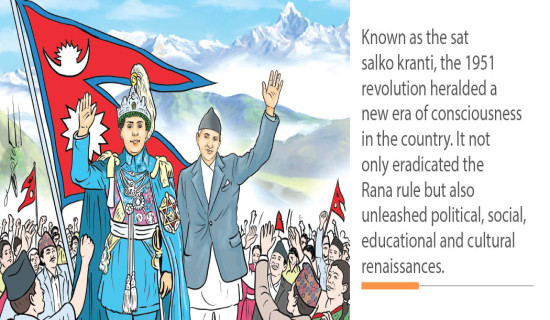

Located west of Hospital Road in the industrial city of Biratnagar, where the call of Nepal’s democratic movement first echoed, the Koirala Niwas was never just a private home. For those who believed in the Nepali Congress and democracy, it was regarded as a pilgrimage site. Nearly 120 years ago, the house was built by Krishna Prasad Koirala, who planted the seeds of democratic consciousness here.

After the death of Chandra Shumsher, Krishna Prasad returned to Nepal and lived in this very house, launching campaigns of social reform and political awakening. Amid the repression of the Rana regime, the courage to raise a citizen’s voice came from this family.

Among his six sons, the eldest, Matrika Prasad, Bishweshwar Prasad (BP), and the youngest, Girija Prasad Koirala, went on to become Prime Ministers of Nepal. The emotional and ideological foundations of their political journeys were rooted in this residence. Countless moments of democratic movements, organisational efforts, and strategic discussions unfolded in this courtyard.

Spread over one bigha and 16 katthas of land, the property was divided and gradually sold. The southern portion fell to BP’s children, sons Prakash, Dr Shashank, and Shreeharsha, and daughter Chetana, who later sold the land. The northern portion was sold by Jyoti, son of Tarini Prasad. The eastern land went to Sujata, daughter of Girija Prasad, who later transferred it in the name of the Girija Prasad Koirala Foundation and built a structure there. The original house and courtyard went to Shekhar, who inherited the responsibility of preserving this historic legacy.

Nepali Congress, founded by BP, once dreamed of buying back all the land and building a museum there. A proposal was even put forward in Morang, but it never became a reality. As a result, a place considered the centre of political history gradually shrank into the narrow confines of private property.

This process did not just reduce the land area; it disrupted the continuity of collective memory. Although privately owned, Democrats saw it as a shelter of politics, a sacred place where Nepal’s democratic journey had begun. Even decades ago, there was a strong belief that the residence should be turned into a grand museum and learning centre for Congress ideology and democratic values. But due to a lack of consensus within the Koirala family, the residence was formally partitioned in 2015.

The Gen Z movement in September last year dealt an even harsher blow to this historic house associated with Nepal's every democratic moment, nearly erasing its history. The house had no connection to corruption, nor had it sheltered corrupt individuals. The century-old wooden house, standing firm for over a hundred years, was reduced to ashes in a matter of moments. It was not just wood and furniture that burnt. Century-old documents turned to ash. Records of key decisions made by Matrika, BP, Girija Prasad, and Nona Koirala were destroyed. That a house which had witnessed movements, dialogue, and ideological debates became a target of violence was itself a tragedy.

Within the Nepali Congress, a well-known anecdote is often cited when discussing accountability. It is said that BP Koirala once noticed two extra bundles of firewood being used in his kitchen and questioned where the additional bill had come from. On another occasion, when his own brother bought new shoes before receiving his salary, BP reportedly asked where the money had come from and removed him from his role as personal secretary. The Koirala Residence stood as a symbol of such democratic values and ideals. The Gen-Z revolt had no direct demands tied to the residence. There was no disagreement linked to it, yet the house was set on fire and reduced to ashes.

Some important materials had already been sent to the BP Museum earlier. Several significant artefacts and documents from the residence had been transferred to the BP Museum in Sundarijal years ago. These included a 114-year-old chest, rice storage vessels, the amended party statute presented by BP at the party’s seventh general convention, traditional utensils, a khukuri, a hand microphone, and a cash box. Books read by BP during his lifetime and a diary used during his exile in Forbesganj, India, were also handed over. The diary contained records of expenses incurred during the movement and poetic verses expressing faith in its success. However, many other important documents and archives remained in the residence. Had all those materials been handed over to the museum, living history might have been preserved. After the arson, only ashes, burnt wooden fragments, and a collapsed structure remain. This was not merely a physical loss, it raised serious questions about our collective responsibility toward history. It has fostered a dangerous narrative that anything can be done in the name of revolt.

The Koirala Niwas was not just a witness to major political and democratic movements; it often led them. From preparations for revolution to election campaigns and people’s movements, the house played a central role. From the 1959 general elections until shortly before Girija Prasad’s death, key political announcements and decisions were often made from this residence. Even after 1991, Girija Prasad rarely launched new political agendas from Baluwatar. Instead, he would come to the Koirala Residence, call party colleagues and journalists, and make announcements from there. It became almost a tradition.

During the first Constituent Assembly elections in 2008, the Maoists dominated the political landscape, and combatants in cantonments had not yet been integrated. At that time, not only the police, army, and national intelligence agencies, but also party committees from the village to the central level, repeatedly warned that the Congress would face a humiliating defeat if elections were held immediately and suggested postponement. But Girija Prasad came to the Koirala Residence in Biratnagar and declared: even if Congress loses, elections must be held. Elections come every five years, he said—but if elections are not held now, the country itself will lose. True to his words, the Congress, which came second in 2008, emerged first in the 2013 elections. From Biratnagar, he also made important statements on the monarchy. After the 2006 people’s movement, there was an intense national and international debate on whether to retain the monarchy. The Nepali Congress was relatively moderate toward the monarchy, but Girija Prasad believed the king’s rigidity was the real problem. He suddenly came to Biratnagar and stated that if the king did not accept a baby king arrangement, the Congress would move toward republicanism. He warned that republicanism was the demand of youth, students, and the movement – and that the Congress would not be able to withstand the storm if the king refused compromise. His words later proved prophetic.

This house was not merely a geography of family inheritance. It was an open platform of political culture, ideas, and debate. Ideas that emerged from here would create ripples nationwide. Media influence was not as strong then. Leaders did not call press conferences at airports as is common today. If Girija Prasad conceived an idea in Kathmandu, he would travel straight to the Koirala Residence and speak to journalists from there. That is why the residence once functioned as the axis of politics. His sister-in-law Nona Koirala also lived there. Discussions between brother-in-law and sister-in-law on both family matters and major political decisions often took place in this residence.

Today, the Koirala Residence resembles a bell without its clapper. With modern urban expansion, commercial complexes have risen around it. Once, anyone travelling to the then Koshi Zonal Hospital for treatment could point to the house from the road and say, “That is the home of BP and Girija.” Now it is hidden behind walls and buildings. After the Gen Z revolt, it resembles a skeleton. Charred wooden stumps and a few surviving but useless iron cabinets are all that hint at its existence.

After the arson, discussions on reconstruction have begun. The family and stakeholders are trying to preserve what remains. But reconstruction should not mean merely rebuilding walls. It requires a vision to collect historical memories, archives, and documents and restore the spirit of the place. Physical structures can be rebuilt, but lost authenticity and artefacts are hard to recover. The story of the Koirala Residence is also a story about legacy.

It raises the question of how to balance private ownership with public history. If timely coordination and long-term planning had been in place, the site might have survived today as a museum or research centre. Currently, Dr. Shekhar Koirala, son of Girija Prasad’s elder brother Keshav Koirala, lives in the house. The press conferences and discussions he holds there often evoke memories of Girija Prasad. Yet the great emotional pride that democrats once felt at merely mentioning the Koirala Residence, the passion and reverence it inspired, will take time to return.

(Written by TRN's Morang-based reporter, this write-up is translated by Sushma Maharjan.)