- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

I am fully confident March 5 elections will take place

Preparations are now underway for the House of Representatives election scheduled for March 5, 2026. When the main responsibility of the interim government is to hold the elections, the Election Commission has reiterated its commitment to conduct the polls in a free and fair manner. Still, security arrangements, rising youth expectations, the influence of the Gen-Z movement, and the spread of misinformation on social media have been the major public concerns.

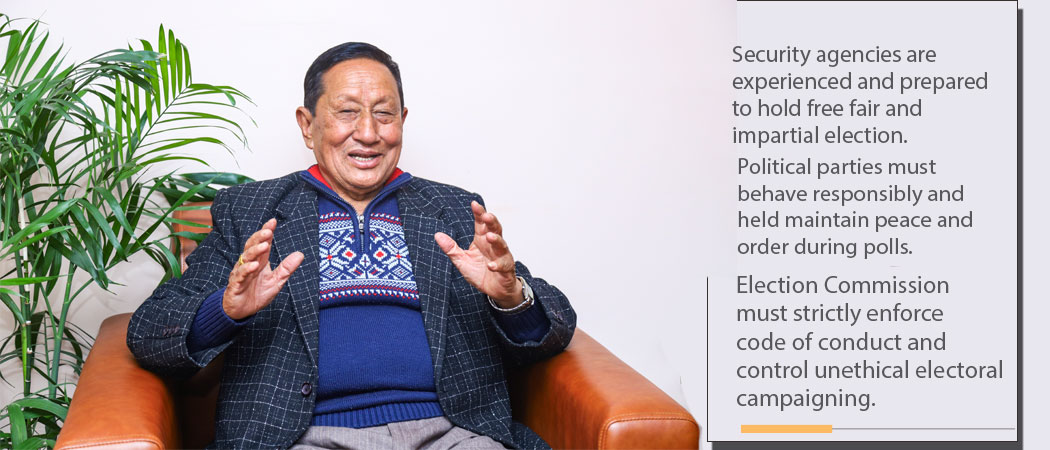

In this context, Arpana Adhikari of The Rising Nepal, together with a Gorkhapatra team, spoke with Dolakh Bahadur Gurung, former Acting Chief Election Commissioner. A key figure to successfully hold the historic 2008 and 2013 Constituent Assembly elections, Gurung shared the challenges of past polls, assessed the country’s present level of preparedness, and outlined what must be done to ensure a widely accepted election this time. Excerpts:

During your tenure at the Election Commission, two important Constituent Assembly elections were held. How do you compare the two elections with the upcoming March 5 polls ?

Elections are about securing the people’s mandate and must always be free, fair, and impartial. The Constituent Assembly (CA) elections of 2008 and 2013 were held in a post-conflict environment, with the 2008 election forming a key part of the peace process to draft a new constitution. The first CA could not finalise the constitution drafting process, leading to the election to the second CA in 2013, which faced challenges including boycotts by some groups.

During the 2008 CA elections, the security situation was challenging, and many legal provisions were not fully defined and electoral system had not been finalised. Yet, with cooperation from the government, Election Commission, political parties, and the then rebel Maoists, the elections were successfully conducted They were free, fair, and widely accepted. It was accepted at both the national and international levels. Voters, at the heart of the process, participated actively in both 2008 and 2013 elections.

Similarly, the main purpose of the present election is to institutionalise the Gen-Z movement, strengthen democracy, and meet the expectations of the Nepali people, including controlling corruption, ensuring good governance, and promoting youth participation. It is being conducted under the current Constitution, this election aligns with public aspirations.

You have described the background and circumstances of the 2008 and 2013 elections. Now, with the House of Representatives election scheduled for March 5 next year, how do you evaluate the Election Commission’s preparedness for the elections ?

Looking at the current context, I am fully confident that the upcoming election will take place. It must take place. Successful elections rely on political dialogue, participation of the political parties, voter engagement, security, and the commitment of both the government and the Election Commission. Today, the situation is very different from the past, all major parties are participating, over 800,000 new voters have been registered, and the interim government has a clear mandate to conduct the polls. The Election Commission has reported it has completed 70 per cent of preparations. It has claimed that it is fully capable of managing polls while security agencies are developing integrated plans and expressing high confidence.

The Gen-Z movement has played a key role, pushing for capable representatives, electoral reforms, constitutional amendments, and greater youth participation in governance and Parliament. Unlike in 2008 or 2013, there are no boycotts or major disruptions this time, and all parties appear ready to participate. For these reasons, this election is both necessary and inevitable.

Given that this is a snap poll in nature, and during the Gen-Z movement, many courts and police buildings were burnt, and several convicts declared guilty by the court are still absconding, what additional precautions should the government and the Election Commission take ?

Security is the most essential requirement for a credible electoral environment. It underpins every aspect of an election, from administrative and operational management to handling of the political challenges. Political parties and candidates must be guaranteed safety, voters must feel secure travelling to polling centres, and election staff, journalists, and observers must be able to perform their duties without fear. Safe delivery of election materials, protection of ballot boxes, and integrity in counting and announcing results are also critical.

Integrated planning is vital. The Election Commission’s joint committees assess geography, sensitivity, existing challenges, and potential threats, categorising areas as normal, sensitive, or highly sensitive. In the current context, focusing on sensitive and highly sensitive areas is sufficient. Even if some convicts remain at large, the deployment of security personnel and the mobilisation of political parties naturally stabilise the election environment and enhance security. Security is not solely the responsibility of the forces, when parties coordinate at the ward and household levels and local election support committees are active at each ward, polling centre, and constituency, they also help maintain safety. With strict enforcement, most weapons are likely to be surrendered or abandoned, and those who remain at large can be apprehended.

Past election, despite violent incidents, including 64 deaths in 2008, and around 15–16 in 2013, were effectively managed by our security agencies. They remain highly experienced, confident and fully prepared to ensure security for this election. Given this readiness, there is no reason to expect the level of insecurity that some fear.

While some political parties have expressed concerns about election security, how crucial is it for the parties and Gen-Zers, who led the recent movement, to actively help create a safe, fear-free environment for voters ?

Certainly, because security is not the responsibility of the security agencies alone. Political parties themselves carry the primary responsibility and duty on the ground. If parties claim there is no security, yet engage in unhealthy competition, marching in processions, shouting provocative slogans, or making speeches that incite disorder, security forces alone cannot manage the situation. That is why the main responsibility lies with the players in the field. The Election Commission acts merely as a referee; these are the parties and candidates for whom security arrangements are ultimately made. Democratic parties must uphold the law and electoral code of conduct, while cooperating fully. If all parties do so, I believe this election can be conducted in an exceptionally clean, free, and fair manner. Voter participation is likely to be very high. The people are eager, Nepali citizens are deeply committed to elections, treating them almost like a festival or celebration.

Having served as Chief District Officer in Solukhumbu and other districts, what is your assessment of holding the election in a single phase, given that snowfall is likely in March first week, which will make travel difficulties in some Himalayan areas ?

Since the President has announced the policy of holding the election in a single phase, I won’t comment on whether it was right.

From a security perspective, two phases might have been easier arrangements. Concerning the weather, elections have previously been held in months like June and December, during paddy harvesting or other challenging conditions. In some hilly and Himalayan districts, snowfall is possible. At present, the priority is to hold the federal parliamentary elections promptly, restore Parliament, and implement the demands of the Gen-Z movement. If weather prevents voting in some areas on March 5, those elections can be postponed by a few days and managed locally. Only a few northern or high-altitude polling stations may face difficulties. The Election Commission is fully capable of managing these situations, which do not pose a major concern.

The Gen-Z movements led to the fall of a powerful government and the early dissolution of the House of Representatives. How should political parties ensure that the demands and aspirations of the youth, particularly Gen-Z, are effectively represented, starting from the candidate selection process ?

As I mentioned earlier, the election environment is already taking shape, and the election must take place. However, several challenges remain. There are also issues of uncertainty, confusion, and doubt. For example, the Supreme Court is currently considering a case on whether the election should proceed and whether Parliament should be reinstated, leaving people waiting for clarity. Given this, it would be ideal for the election to be held as soon as possible. The interim government, under Prime Minister Sushila Karki has been engaging with political parties. However, in my view, the government needs to take a more proactive role. When parties attend meetings called by the Prime Minister and provide their suggestions, it demonstrates their acceptance of this government and its election process. While creating a conducive political environment is the government’s responsibility, facilitating the process falls to the Election Commission. All parties must consider the demands of Gen-Z youth and work to address them.

For Gen-Zers, who are driving change through this election, organisation and unity are crucial. With many different groups and varied demands, they risk weakening their impact. They should engage directly in the election, supporting capable young candidates within parties or standing as independents. They should also work at the grassroots level, visiting households to guide voter choices, enforcing the code of conduct, and avoiding superficial campaigns such as feasts or gatherings. Instead of remaining in district centric, they must mobilise at the village level through committees or local teams. Ultimately, the Gen-Z movement was a means to tackle corruption and promoting good governance. To achieve this, the new generation must remain active, engage directly with the public, rather than allowing themselves to be placated.

Nepal’s proportional representation (PR) electoral system aims for inclusivity, yet leaders often favour family or close associates. Why is the Election Commission unable to prevent this ?

Questions are often raised about election policies in Nepal. They are sometimes drawn to controversies. However, the Election Commission introduced a unified Election Commission Act a year and a half ago, which could have allowed some improvements.

Electoral system is perfect, and Nepal’s proportional representation system is no exception. Its effectiveness depends on proper implementation. Parties must avoid repeatedly nominating family or close associates and recognise candidates rejected by voters. Instead they should bring in new faces. The Election Commission can manage elections but cannot control party behaviour. Parties must follow constitutional provisions, such as reserving 33 per cent of seats for women. The commission can monitor compliance, but it is ultimately the party’s responsibility. The Gen-Z movement’s push for governance reforms reflects growing public dissatisfaction. A well-run election, backed by voter education, allows informed choices, ensures accountability, and ultimately shapes stable government formation.

There has been a significant increase in the registration of new political parties. With more parties, seats are further divided, raising concerns about whether a stable government can be formed. What is your view on this ?

That possibility always exists. But what matters most is reaching out directly to voters. Gen-Z youth should go door to door in villages, explain their choices, and encourage people to vote for capable candidates to secure a majority. Healthy competition among strong parties is essential. During elections, psychological pressure, as well as the misuse of influence, muscle, and money, might take place. However, the key is voter education. Both the Election Commission and political parties must work to reduce invalid votes, which were around 5 per cent in the previous election. Voter education raises awareness and ensures citizens exercise their right to vote. Even if parties or candidates boycott, voters should participate. Historically, Nepal's elections have both shaped and been shaped by the political environment. Voter engagement is high, for example, proportional representation elections have seen up to 80 per cent participation. Once voting occurs, parties are compelled to respect public opinion.

With the rise of fake news and AI-generated content on social media, how should the Election Commission ensure free, fair, and credible elections, and what monitoring structure is needed ?

A key point is that the Election Commission must not only issue the code of conduct but also enforce it rigorously and take necessary action. While the code itself is strong, its main weakness lies in enforcement. Even parties that formally agree to abide by it often fail to comply with. In the media sector, some outlets report responsibly, but many spread misinformation, causing public confusion and, in extreme cases, endangering lives. During elections, media monitoring should be carried out by an appropriate authority, as the Election Commission has done in previous years, with corresponding actions taken. Even if full enforcement is not possible, partial measures can still be effective. Ultimately, the code of conduct ensures adherence to rules and the law.

Despite fixing expenditure ceiling for elections, some parties still spend millions to secure victory. Since the Election Commission can disqualify candidates for proven violations but hasn’t enforced this strictly. Has it not encouraged the parties to make elections more expensive ?

Many political parties tend to select wealthy candidates, while those who have dedicated their entire lives to the party and to democracy often do not receive tickets, or even if they do, they cannot afford to contest. There is also a growing belief that whatever money is spent during elections can later be recovered, which further fuels excessive spending. Therefore, the Election Commission must be willing to take action without favour. Previously, violations of the code of conduct, such as excessive banners, posters, wall paintings and street slogans were common. While these have been curtailed and improvements made, stronger enforcement is still needed. If candidates organise feasts and gatherings against the code, the Gen Z youth should report these immediately. Election Commission teams and security agencies must be empowered to act on such complaints on the spot. That is why I believe young people, especially Gen Zers, must go to villages, discourage illegal and unethical campaign practices, and encourage voters to elect good candidates.