- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

Technology can be used to ensure voting rights for Nepalis living abroad: Upreti

As Nepal gears up for the mid-term elections scheduled for March 5, 2026, expectations are particularly high among the nation’s youth and the millions of Nepalis living abroad. Ensuring a credible poll, safeguarding voting rights, restoring public trust, and maintaining effective security arrangements have emerged as major national concerns.

In this context, Arpana Adhikari of The Rising Nepal, along with the team from Gorkhapatra, spoke with former Chief Election Commissioner Neelkantha Upreti. The discussion focuses on the responsibilities of the Election Commission, the key challenges facing the upcoming polls, and the reforms required to ensure a smooth and democratic electoral process. Excerpts

It has been two months since the election date was announced, and efforts to create a conducive environment are still underway. Do you think the progress made so far is adequate?

Nepalis at home and abroad have expressed concern that election preparations are moving slowly. However, announcing an election date and preparing for the election are two different processes. Updating the voter list and confirming the political parties and independent candidates participating in the polls are essential steps, and without completing these, the election cannot proceed.

This election comes at a special and unprecedented moment. The mid-term polls were not anticipated, and the Gen-Z movement created nearly six weeks of a highly sensitive situation. As a result, the election was announced by invoking special provisions that were not previously part of the regular law-and-order framework. The Election Commission now has the responsibility to conduct an emergency election originally scheduled for 2084. Given these conditions, it is understandable that preparations cannot move smoothly immediately after the announcement. Still, it is true that the Commission’s progress so far has not been fully satisfactory.

What do you see as the major challenges facing this election?

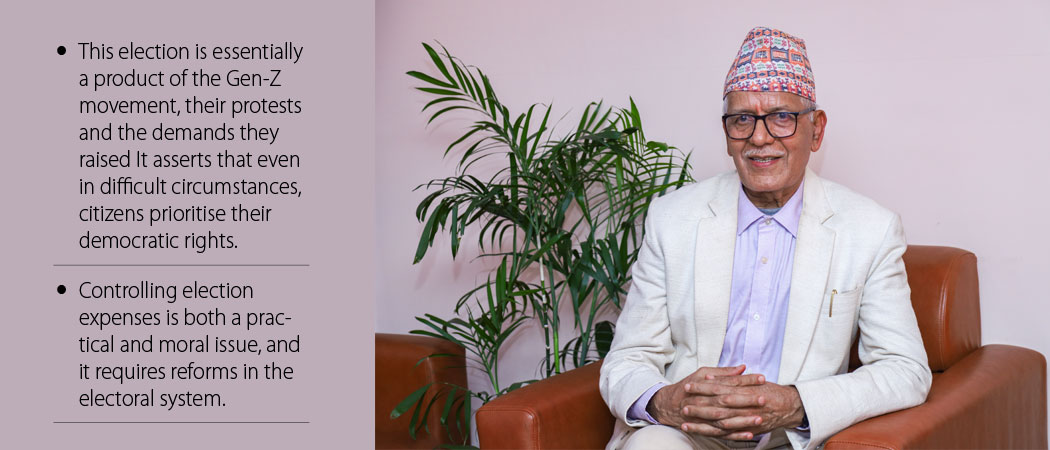

To understand the major challenges of this election, we must first understand how it came about. This election is essentially a product of the Gen-Z movement, their protests and the demands they raised. The young generation pushed for reforms, such as changes in the electoral process and ensuring voting rights for Nepalis living abroad. The election was called as an effort to respond to these demands, and this context itself has created unique challenges for the electoral process.

Millions of Nepalis live abroad, and there has been ongoing discussion about granting them voting rights. Although the Supreme Court has already directed the government to ensure this, there is still no law in place. How can this be made possible?

It is certainly possible. This should have been addressed long ago, especially since the Supreme Court directed the government to ensure voting rights for Nepalis abroad nearly a decade ago. If we treat that directive with the same weight as a constitutional requirement, previous elections should not have excluded overseas voters.

Now, with the election announced in response to the recent movement and its demand to guarantee voting rights for Nepalis living in more than 119 countries, it is essential to identify how many still hold Nepali citizenship and ensure they can vote from where they reside. This is not a regular election. It has been called under special circumstances. If we fail to address the core issues that drove this mid-term election, holding it would serve little purpose, and it would have been better to wait for the 2027 election.

Given the legal, technical and time constraints, how feasible is it to guarantee voting rights for Nepalis living abroad, especially when the voter list for overseas Nepali citizens has not yet been updated?

We cannot say that the voter list for Nepalis living abroad is not updated. About ten years ago, voters who had turned 16 were enrolled, and voter IDs along with photos were issued. Nepali citizens reside in 119 countries, with the majority in India, followed by the Middle East, Europe, and America. Citizens already listed in the voter rolls should be allowed to vote under both electoral systems, First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR).

Ensuring voting rights for Nepalis living abroad is now possible through technology. Technology can be used to ensure voting rights for Nepalis living abroad and for those who have migrated within the country for work or other opportunities through an inter-constituency voting system. For Nepalis living abroad, in-person voting reaching the diplomatic missions is not feasible for all. So, the I-voting, along with OTP-based authentication and a secure virtual ballot box, is the most practical solution. Nepalis reside in 119 countries, and they should be able to exercise their voting rights. Around 50 countries, including the Philippines use the technology for elections, though I-voting is less common. Even if we lack certain technology, systems available globally can be adapted for use in Nepal. With proper planning, I-voting can be successfully implemented. The March 5 election date should not be considered final if adjustments are needed to ensure voting rights of Nepalis living abroad, and achieving this would be a historic milestone for the Election Commission.

I-voting can also be implemented within the country. Those with internet access could cast their votes 1–2 days in advance, while an e-voting system could be provided for those without access. This approach is cost-effective and would save millions of rupees spent on ballot papers and ballot boxes.

How can the Election Commission verify genuine voters among Nepalis living abroad who are on the voter list but may have acquired foreign citizenship?

This is an important issue. Nepalis living abroad who are on the voter list and hold Nepali citizenship, but have also acquired foreign citizenship, can be identified by asking them to submit their National ID and e-passport. Voting rights should be granted only to those who complete this process online. They must also provide a formal self-declaration confirming that they have not obtained foreign citizenship or misused their voting rights, and acknowledging that any violation of the law would be punishable.

Prime Minister Sushila Karki has advocated for inter-constituency voting, a key demand of the Gen-Z movement. How feasible is this proposal?

This can be made feasible with the use of technology. Keeping ballot papers of every constituency in each polling station is impractical, but e-voting can solve this. Pre-voting could be conducted three to four days in advance, with votes securely stored electronically and counted transparently in the presence of stakeholders. Once technology is adopted, inter-constituency voting should not be limited to the PR system alone. All Nepalis, whether in Siberia, Mexico, or at home, deserve equal rights in both electoral systems. Guaranteeing voting rights in only one system does not fully uphold democratic principles.

We can manage this. Many countries already use advanced election technology, and strong mechanisms can be developed to prevent cyber-attacks, system hacks, or manipulation. The firms that supply these systems have made them increasingly secure, and today’s cyber tools can safeguard every stage of the electoral process, from voter registration and verification to vote casting, data processing, and protecting against both accidental and intentional disruptions. Modern technology is more reliable than manual methods.

We have already used computers to fly planes safely and have been doing transactions of millions of rupees through secure OTP systems. If we trust technology in these areas, we can trust it for voting as well. However, with only four months left, we must act quickly: identify the right technology, decide where to procure it from, and begin implementation. Without guaranteeing the voting rights of Nepalis abroad and enabling inter-constituency voting, the purpose of the election cannot be fully achieved.

After the Gen-Z movement, Nepal’s security situation has become highly sensitive. During the protests, many weapons were looted and prisoners escaped from jail, and the police are still working to recover the weapons and rearrest the escapees. In this critical context, what steps should the Commission and the government take to strengthen security?

Election security is always a sensitive issue. We faced a similar situation during the 2070 B.S. election, when 33 parties boycotted the polls, called a 10-day nationwide strike and even carried out explosions. Despite these challenges, voters were not discouraged; while earlier elections saw around 65 per cent turnout, that year it rose to 78 per cent. It asserts that even in difficult circumstances, citizens prioritise their democratic rights.

The government is currently working to recover the looted weapons and rearrest prisoners at large, and this process will continue. All Nepalis, along with the security agencies, must move ahead strategically. Voters’ participation and courage are the greatest strengths of democracy. I believe the current government will manage the situation and create a conducive environment for the elections. With coordinated, strategic efforts, our security agencies can effectively handle the challenges.

The election date has been set for March 5, when high-hill and mountainous regions may experience snowfall. Given these weather conditions, do you think it is feasible to hold the election in a single phase?

I had not considered this issue earlier. Before the 2064 B.S. election, there was unexpected snowfall even in areas like Chitwan and Butwal, so similar situations could occur again. We have always advised avoiding periods prone to adverse weather.

During the 2070 B.S. election, we analysed 50 years of rainfall data and found that the monsoon typically begins around Jestha 10, so the election was held before that. If snowfall becomes a concern for the March election in high-hill and mountain districts, and if we want to conduct the poll nationwide in a single phase, the date may need to be shifted.

Since we also have responsibilities like procuring technology and managing logistical arrangements, the Election Commission should recommend that the government consider rescheduling the election toward the end of Baisakh.

As a former Chief Election Commissioner, what strategies would you recommend to regulate and reduce excessive cost of conducting elections ?

Controlling election expenses is both a practical and moral issue, and it requires reforms in the electoral system. Currently, irregularities exist in both systems, the PR system often prioritises nepotism and favoritism, while the FPTP system has become a process of buying and selling candidacies, there have even been cases of individuals selling property to secure party nominations. This makes elections expensive for both political parties and the Election Commission.

I believe Nepal should adopt a full PR system instead of the current mixed system. The problem is not the system itself, but the tendency to misuse it. A full PR system allows voters to cast their votes from anywhere in the country and ensures proportional representation of all communities based on population. Adopting this system could reduce election costs by around 40 per cent for Election Commission and also from political parties. Many countries have achieved greater stability and economic development by implementing full PR systems, including South Africa, Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

-original-thumb.jpg)