- Tuesday, 3 March 2026

An Account Of Trans-Himalayan Relations

Nepal and Tibet have shared a relationship of both affection and animosity for millennia. Formal exchanges between the two began with the spread of Buddhism, which was further cemented by the marriage of Lichchhavi Princess Bhrikuti to Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in the seventh century. The 33rd King of Tibet, who was also married to the Chinese Princess Wencheng, founded the Tibetan Empire and introduced Buddhism to his kingdom. While the two countries were long-standing trade partners, they also fought several wars over the mountains of the mighty Himalayas and Tibet, and signed a number of treaties.

However, the Himalayas themselves, along with the lack of reliable connectivity and infrastructure, discouraged people-to-people interaction and seamless trade. As of November 2025, both trade passes between Nepal and China at the Tibetan border – Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani – remain inaccessible. The Kathmandu–Kodari Highway and Syaphrubesi–Rasuwagadhi road have been damaged by floods and landslides, while the Miteri Bridge at the Rasuwagadhi border was swept away by floods during this monsoon.

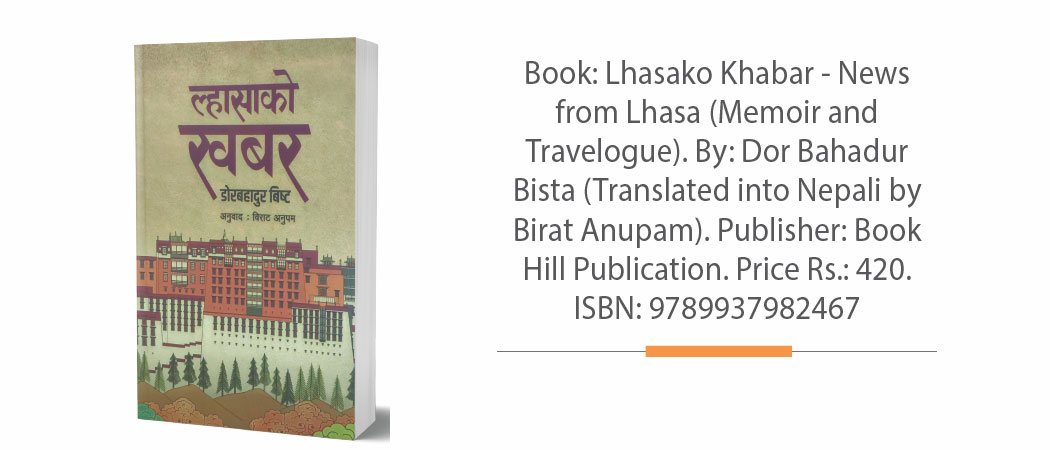

Thus, even today, Tibet has remained an enigmatic Himalayan Shangri-La for Nepali people. It was even more so in the 1970s, when road access was poor despite the opening of the Kathmandu–Kodari Arniko Highway. Sociologist and diplomat Dor Bahadur Bista recounts the hardships of reaching Lhasa and life in the Tibetan capital in his book Report from Lhasa, the Nepali translation of which has recently been published. Translated by Birat Anupam into fine, accessible Nepali, the book narrates the arduous journey from Kathmandu to Lhasa across the formidable Himalayan range.

A sociologist and anthropologist by education and profession, Bista was appointed Consul General at the Consulate General of Nepal in Lhasa by King Birendra in 1972. The Nepali Consulate General in Lhasa had been formally established in 1960, following the 1956 Nepal–China Treaty of Peace and Friendship and subsequent agreements. After arriving in Lhasa, Bista did not merely fulfil his duties by idling in the office and engaging in occasional diplomatic and ceremonial activities in the sacred city. He reached out extensively to government offices and representatives of Beijing in Lhasa, to the Nepali community – both the traders from Nepal and the half-Tibetan children born of Nepali men and local women – and sought to address their concerns. The warmth extended by the people of Tibet towards the visiting Nepali diplomat was exceptional and heart-warming, evident from the very start of his journey.

Bista frequently recalls references by Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, who upheld the philosophy that the sovereignty of a nation can never be measured by its geographical size. The hospitality and last-minute support extended by the authorities in Tibet and Beijing during his sudden trip to Beijing – where he was included in the delegation for the official visit of Nepali Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista in November 1972 – serve as further proof of this principle. Although flights from Lhasa to major Chinese cities were rare and travel was difficult, Chinese authorities not only secured him a seat on a plane but also ensured he was accompanied throughout his journey. During my own stay in Beijing in 2024, I too witnessed the respect and priority given by the Chinese government to heads of state and government, even from smaller and island nations such as Nepal and Nauru.

Bista also takes readers on a tour of the Himalayas and the historical and cultural monuments of Beijing. En route to Lhasa from Kathmandu, the mesmerising Himalayan range both fascinates and troubles him. His astonishment is natural when, after crossing the mountains, he finds that they appear on the southern side – the exact opposite of what one sees from the north. Bista and his family travel through snow-clad mountains and, at times, cave-like tunnels formed by heavy snow. They breathe a sigh of relief upon reaching Shigatse, after crossing a high pass at an altitude of 4,500 metres.

Bista provides a vivid account of how Tibet was changing at that time, transforming from a theocratic society into a socialist one. Where once hundreds of statues of Buddha, gods and demons lined the roads and adorned houses, when he reached Lhasa, the pagodas and billboards were instead filled with messages from Chairman Mao.

Even the elderly, who had once bestowed blessings for long life and good fortune, now wished for Mao’s longevity and exchanged his quotations. Numerous communes had been established around the city, which was once one of the oldest Buddhist strongholds. The book also takes readers to the world-famous Potala Palace and the shrines of the Lamas, astonishing them with their magnificence and serenity.

The book tells a story that can never be seen again: hardships in Lhasa that will never be experienced again, journeys that will never be undertaken again, and a social transformation that will never happen again. It stands as a testament to Nepal–Tibet, or Nepal–China, relations, which have long been cordial and vibrant. Bista’s writings are drawn from lived experience, with little adulteration by opinion, political statements, or personal bias – whether towards communism or Buddhism. Yet, what shines through unmistakably are his feelings towards the people and the environment.

-original-thumb.jpg)