- Friday, 13 March 2026

From Demography To Dissent

Nepal’s Gen-Zs And Dynamics Of Youth Uprising

In recent decades, scholars have divided populations into generational cohorts to explain how shared historical and social experiences shape collective values and behaviours. Much of the current thinking around generational cohorts owes to the publication of W. Strauss and N. Howe’s Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584–2069 (1991), which outlined distinct generational prototypes in U.S. history. Later, the Pew Research Center’s Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins by M. Dimock (2019) provided more formalised generational boundaries.

In these prototypes, each cohort reflects the social context of its formative years. For example, the Silent Generation (~1928–1945) was shaped by war and economic hardship, fostering discipline and conservatism. The Baby Boomers (~1946–1964) experienced postwar prosperity, cultivating optimism and ambition. The Generation X (~1965–1980) matured amid political change and technological emergence, becoming independent and pragmatic. Likewise, the Millennials (~1981–1996) are tech-savvy, socially aware, and collaborative. The Generation Z (~1997–2012), true digital natives, are globally connected, entrepreneurial, and mental-health conscious whereas Generation Alpha (~2013–2025) is growing up in an AI-driven, fully digital environment.

Gen Z population in Nepal

Table 1 compares Nepal's total population and Gen Z population across urban and rural areas. It reveals a larger urban concentration of both populations. Whereas 66.2 per cent of the total population lives in urban municipalities, the Gen Z’s proportion is 66.5 per cent. The rural areas, by contrast, account for only 33.8 per cent of the total population and 33.5 per cent of the Gen Z population. This close alignment suggests that the Gen Z distribution closely mirrors the overall population trend, with slightly greater urban concentration among the younger generation.

A closer look at the age composition by geographical unit reveals that the share of Gen Z within the urban population is 31.0 per cent, while in the rural areas it is slightly lower at 30.6 per cent. This indicates that Gen Z forms nearly a third of the population across both spatial units, but with a marginally higher representation in the urban areas. The national average stands at 30.9 per cent, showing consistency across regions. These figures suggest that although urban areas attract more of the Gen Z population numerically, the proportional representation of this generation is relatively uniform throughout the country, reflecting nationwide demographic patterns.

From a developmental and policy perspective, the high concentration of Gen Z (2/3rd) in the urban areas indicates growing demand for expanded infrastructure, education, employment, and digital services tailored to a tech-savvy population. At the same time, the sizeable rural Gen Z population highlights the need for investments in youth empowerment, education, and connectivity. These demographic patterns are critical for designing inclusive growth strategies and youth-focused policies that balance urban and rural priorities in national development planning.

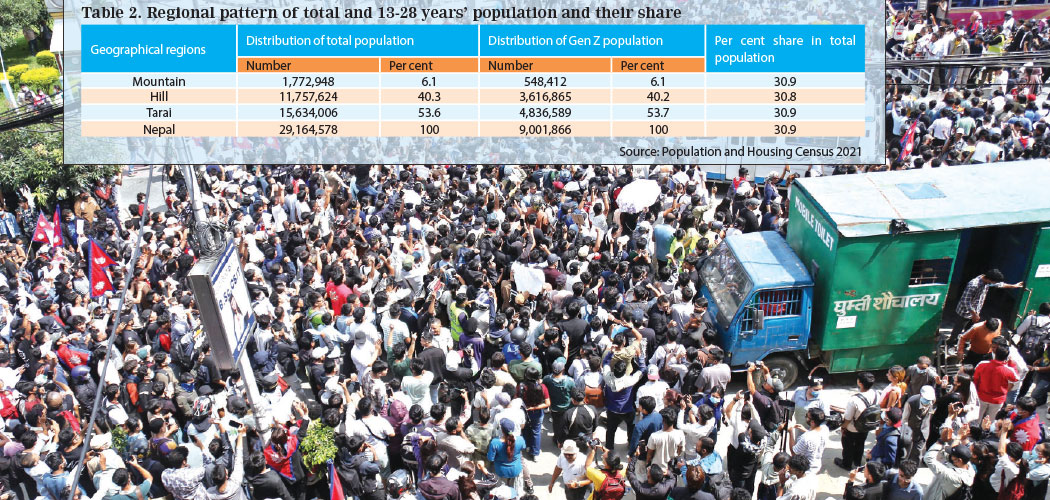

Table 2 provides a regional distribution of Nepal's total and Gen Z populations. It shows that the Tarai region shares the largest proportion, with 53.6 per cent of the total population and 53.7 per cent of the Gen Z population. The Hill region follows with around 40 per cent of both total and Gen Z populations, while the Mountain region accounts for the smallest share, i.e., only 6.1 per cent of each. This proportional alignment indicates that the Gen Z population is distributed across regions almost identically to the total population.

When looking at the per cent share of Gen Z in the regional population, all three geographical regions show remarkable uniformity, each with Gen Z comprising approximately 30.8–30.9 per cent of the population. This consistency suggests that generational distribution is balanced across Nepal’s diverse geographical regions, despite stark differences in population size and density.

Gen Z uprising

Over the past decade, Nepal's Gen Z population has come of age amid sweeping political changes and chronic instability. From witnessing wrangling in promulgation of the 2015 Constitution amidst the dissatisfaction in Madhes and the creation of a federal system with seven provinces, and the first general elections under the new framework in 2017, this generation grew up watching history unfold but from the sidelines.

The formation of a majority government through the left alliance of the CPN-UML and the Maoist Centre initially promised stability. Yet, it was quickly followed by repeated parliamentary dissolutions, party splits, legal battles, and, eventually, a hung parliament in the second general election. The irony of the third-largest party forming a coalition government, followed by two major parties coming together in 2024 merely to prevent collapse, deepened Gen Z's disappointment with the political class. In the meantime, they observed a widening gap between the promises of multiparty democracy, and its delivery. The very leaders who pledged social justice and economic opportunity seemed to flourish, along with their families, while youth unemployment surged.

This generation, raised in the digital age, is more globally aware than any generation before. With smartphones in hand and access to the world via social media, they watched their peers in other countries demand better governance, transparency, and innovation, and often succeed. Naturally, they expected their own government to ensure quality education, digital freedom, and meaningful employment. Instead, many found themselves forced into the same well-trodden path of foreign labour migration, watching their futures outsourced while nepotism and mismanagement remained entrenched at home.

The ban on social media platforms acted as a spark in a room already filled with political frustration and economic despair. For Gen Z, this was not just about access to TikTok or Instagram; it was a symbolic attack on their space for expression, organising, and resistance. The mass protests that followed were not sudden eruptions; they were the result of years of cumulative neglect, broken promises, and systemic exclusion. It appears that this generation is not simply protesting a policy, but more importantly, they are rejecting a political culture that has consistently sidelined their hopes, silenced their voices, and subdued their hope for the future.

Regional comparison

Nepal’s case is fairly comparable with Indonesia and Bangladesh, both of which have recently witnessed youth-led uprisings and political unrest, rooted in deep-seated frustrations with governance and systemic issues. Despite their different geographical contexts, both countries share notable similarities in demographic composition and governance challenges. Despite similar in areal extent with Nepal, Bangladesh has a significantly larger population. Indonesia, with a population exceeding 270 million as per the 2020 census, reports that Gen Zs make up around 27 per cent of its total population. In contrast, Bangladesh, with an estimated population of over 172 million in 2024, has a considerably larger Gen Z segment proportionally, with reports indicating that nearly 40 per cent of its population falls within this age group. Moreover, a stronger urban concentration is evident in Bangladesh, with nearly 40 per cent of this population residing in urban areas.

While the specific triggers of youth uprisings in the two nations varied, the underlying grievances were very similar. In Indonesia, the prominent point came in August 2025, when revelations about lawmakers receiving hefty housing allowances in addition to their base salaries sparked outrage among the youth. In Bangladesh, the catalyst was the government's reinstatement of a 30 per cent public sector job quota for descendants of freedom fighters, i.e., a policy that many students viewed as unjust and exclusionary. Despite these differences in immediate cause, both movements reflected broader discontent with entrenched systems of privilege and inequity. These protests were less about isolated incidents and more about years of accumulated frustration stemming from perceptions of injustice, lack of opportunity, and difficulty in making their living.

What unites all three cases even more is the generational context and the role of digital connectivity. In all three countries, Gen Z's widespread access to the internet, social media, and peer networks has amplified their political awareness and capacity for collective action. Issues like corruption, high unemployment, elite privilege, nepotism, and rising living costs are not new, but for this generation, they are intolerable in an age of global comparison and digital mobilization.

Compared to previous generations, Gen Zs are better informed, more connected, and increasingly assertive. This makes governance challenges more urgent in countries with large, urbanising, and digitally active youth populations, such as Indonesia and Bangladesh. With Nepal’s youth population projected to remain around 30 per cent for the coming years, the government must take their concerns seriously. Ignoring their grievances risks a repeat of large-scale activism, which could lead to significant loss of young lives and extensive damage to both public and private property.

(The author is a professor of geography and a former chairman of the University Grants Commission.)