- Sunday, 1 March 2026

Glacial Lakes Trigger Deadly Floods

The flash flood of the Bhotekoshi on July 7, 2025, caused by the instantaneous drainage of a supraglacial lake, killed seven people, and another 19 remain missing. The devastating flood was caused by no heavy rain and originated from a supraglacial lake approximately 36 kilometres north of the border with China at Rasuwagadhi.

The flood swept away at least seven bridges, including the main suspension bridge at Timure near the Rasuwagadhi border point, and cut off the Pasang Lhamu Highway, causing disruptions to trade with China. Several houses, hydropower stations, and local businesses were also hit. The disaster occurred due to the sudden drainage of a supraglacial lake, even though no heavy rainfall had been reported.

Similarly, two small glacial lakes burst on May 14, 2025, in the remote village of Tilgau in Namkha Rural Municipality-6 of Humla District. The resulting ice-and-debris avalanche destroyed five wooden bridges, damaged homes, irrigation systems, and hydropower infrastructure, and displaced around 32 villagers into temporary shelters. No rainfall was reported then, indicating glacier instability as the primary cause.

A similar disaster struck about 150 kilometres east of Bhotekoshi, in India's Uttarakhand state. On August 5, heavy rains caused sudden flooding in the Uttarkashi district's Dharali and Sukhi Top villages. The flash flood started when intense rainfall hit the upper areas of the Kheer Ganga River, sending rushing water that destroyed houses and swept away people.

A video posted on X showed how a rush of water, mud, and rocks hit the Himalayan village of Dharali so hard that it tore buildings from their foundations and quickly buried homes up to their rooftops. According to the last media report published a week after the incident, at least 66 people are still missing a week after flash floods hit the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand.

The disaster highlights the Himalayan region's vulnerability to catastrophic weather. From June 13 to 19, 2013, Uttarakhand was battered by nearly 850 per cent above-normal rainfall, unleashing billions of litres across the western Himalayas. The unprecedented downpour killed over 6,000 people across northern India and Nepal, with property damage reaching billions, according to India's National Institute of Disaster Management.

Geologists and disaster experts said that the Dharali flood disaster resulted from a severe natural event (cloudburst and potential glacial lake outburst) and the compounding effects of unchecked development in unstable zones, worsened by climate change.

Rising climate risk

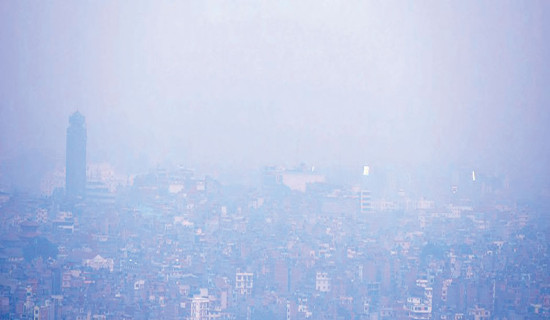

Cloudbursts, landslides, and floods now mark each monsoon season, and data shows a steady rise in these incidents. The terrain is changing faster than most policies can keep up. Experts link these events to changing monsoon behaviour. Rising sea temperatures in the Arabian Sea and warming trends in Central Asia push moist air deeper int o the Himalayas.

"When moisture-rich air hits the mountains, it can form massive storm clouds. When they burst, the impact is violent," said Mahesh Palawat, Vice President of Meteorology at Skymet Weather.

He pointed to the growing presence of cumulonimbus clouds in high-altitude regions. These clouds can rise to 50,000 feet and dump intense rainfall in minutes. Himalayan glaciers are retreating at an alarming pace. Data from the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) show a retreat of 15 to 20 metres per year across major river basins.

Scientists at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology warned that this melt exposes loose rock and soil. The result is unstable land, sudden landslides, and potential Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs).

Risk of temperature rise

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that rainfall intensity increases by 15 per cent for every 1°C rise in temperature in high-elevation areas. This leads to rain where snow once fell, making floods more frequent and severe.

Infrastructure projects in Uttarakhand have expanded quickly. Roads, tunnels, hydroelectric projects, and hotels have been built across the region. Many were approved without proper geological surveys.

Professor Y.P. Sundriyal, a geologist at Doon University, cautioned against treating the Himalayas like stable ground. "These are young mountains, geologically fragile. We're building as if this is a flat plain. One heavy rain can cause massive destruction," he said.

Reports from IIT Roorkee and the National Disaster Management Authority in India (NDMA) showed that large parts of Uttarakhand now fall in high-risk zones.

Uttarkashi has become a hotspot for landslides and cloudbursts. Melting glaciers near Gangotri and Yamunotri increase the risk of GLOFs. Chamoli, especially Joshimath, is sinking. In 2021, over 200 people died when a glacier broke and triggered a flash flood in Raini village. Pithoragarh and Dharchula, on the India-Nepal border, face recurring floods, cloudbursts, and landslides. In August 2023, a cloudburst killed 12 people and cut off road access for days.

Despite the region's vulnerability, disaster experts point out that early warning systems for the Himalayas remain inadequate, unlike those in place for cyclones.

According to Dr Basanta Adhikari, Director at the Centre for Disaster Studies, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, there were no early warning signs from the upstream side during the Bhotekoshi flood. As no early warning monitoring system existed, authorities could not keep people safe from the disaster.

Potential threats of GLOFs

"Nepal's government has been working effectively to improve early warning systems, saving many lives. However, in the case of GLOFs, there is no proper monitoring of glacial lakes because they are located at high mountain altitudes. As a result, we lack timely information about such risks," he said.

Sensors have been installed to detect the risk of glacial lake outburst floods in Nepal. At Imja Lake and the Chho-Rolpa glacial lake area, sensors have been fitted to provide real-time data, which Nepal makes publicly available. Chho-Rolpa is one of the largest and most dangerous glacial lakes in the country, and its rate of melting has been increasing every year.

Ground Report, an Indian environmental news website, quoted Anjali Prakash, a professor at the Indian School of Business and an IPCC report author, stressing the importance of improved monitoring. "We must expand Automatic Weather Stations across the Himalayan region. Early warnings save lives," she stated.

In the case of the Dharali disaster, the Early Warning System failed – there was no functional alert mechanism for the flash flood event.

"We do not have strong technical systems in place to give early warnings for cloudbursts or flash floods in remote Himalayan areas," said Mahesh Palawat from Skymet. "There are no Doppler radars in places like Dharali and in hilly terrain," he explains.

"Tracking thunderclouds is difficult because the mountains block the radar signals. This makes it hard to pinpoint the exact location, and the accuracy can be unpredictable. Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh still don't have enough Doppler radars to cover these regions properly," he added.

According to 2020 data, out of a total of 3,624 glacial lakes across the three river systems – 2,070 in Nepal, 1,509 in China, and 45 in India – 47 have been identified as being at particularly high risk of bursting, 25 of which are in Tibet.

A 2023 study revealed that around 15 million people live in areas at risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), mainly in China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Peru. It has been acknowledged that regional cooperation is necessary to receive information on glacial lake-related events from China, especially regarding the Bhotekoshi and Trishuli river basins.

In 2022, Nepal's Department of Hydrology and Meteorology sent 13 million SMS alerts to at-risk communities. However, these SMS alerts are mostly limited to within Nepal and do not automatically benefit communities in India's downstream regions of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

(With inputs from India by Diwash Gahatraj, who is an independent journalist)

(Aryal is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)