- Saturday, 10 May 2025

Prosperity With Social Justice

For any country to move forward, economic development is essential. In Nepal's case, infrastructure development is slow but ongoing, while economic growth remains stagnant. The country has failed to capitalise on overall development, hindering employment generation and economic stability. The multi-party democratic system has eroded the existing industrial base. To achieve meaningful economic and social progress, Nepal must prioritise agricultural production.

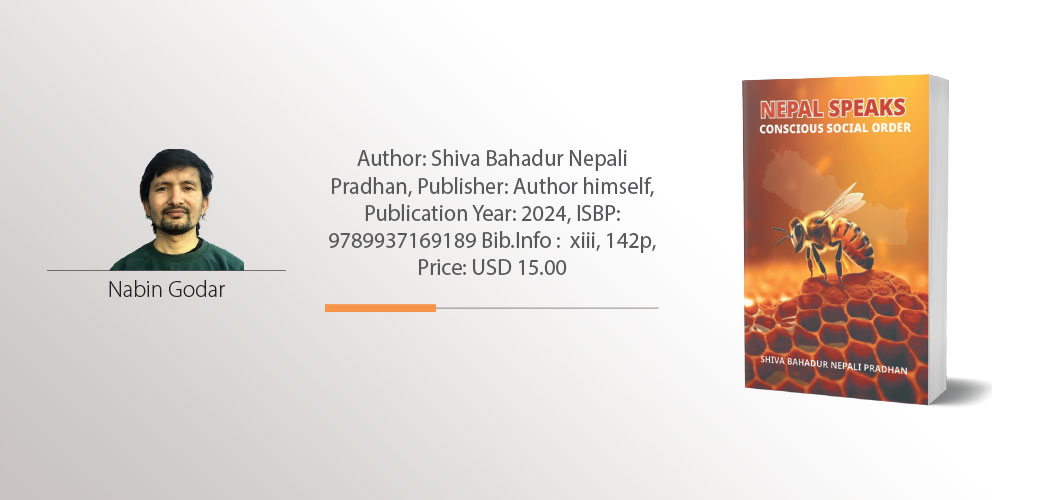

This is the argument presented in the recently published "Nepal Speaks: Conscious Social Order" by Shiva Bahadur Nepali Pradhan. A horticulturalist by profession, 88-year-old Pradhan's book is a compilation of notes and ideas developed over many years.

The thesis presented in the book is that Nepal's agriculture is subsistence-orientated rather than commercial, and only by strengthening it would Nepal prosper further, generating employment and an economy.

The author begins with an overview of Nepal's history, tracing its roots from the Gopal Dynasty to the Shah Dynasty. Each historical period is examined for its contributions to Nepal's political and cultural development. The narrative highlights the country's rich heritage, art, culture, and religious diversity.

Recognising Nepal's rich biodiversity and renewable energy resources, Pradhan stresses the importance of environmentally sustainable policies to ensure long-term prosperity. Despite its abundant natural resources, diverse climate, and cultural wealth, Nepal struggles with poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and political instability.

Pradhan cites that 24% of the population lives on less than $1 per day, and 65% survive on less than $2 per day. Though the per capita income is approximately $300 annually. Our standard of living is three times higher than our per capita income. And unless there is an economic plan to address it, poverty will persist. He has argued that agriculture should also be prioritised for the equitable distribution of resources for poverty alleviation.

He critiques the lack of political stability over six decades of democratic exercises, which has hindered consistent development. He identifies power struggles among political leaders as a major obstacle to addressing critical national priorities such as poverty alleviation, education reform, and employment generation.

He argues while some segments of society enjoy prosperity, many live in abject poverty. This inequality undermines national progress and social cohesion. To address this problem, Nepal should foster a mixed-market economy, and the potential of cooperatives and microcredit systems to empower marginalised communities should be emphasised. He cites examples like Manang Bhot's village organisation system as models of community-driven development.

The central thesis of the book is the propagation of a 'Conscious Social Order', which entails ensuring no one is hungry, no one is illiterate, and no one remains unemployed.

Pradhan outlines both micro-level and macro-level strategies to achieve these goals. On the micro-level, he proposes land reforms; grassroots organizations like consumer groups and civil societies and targeted support for underprivileged communities through education and skill development should be prioritised.

On the macro-level, he argues, strengthening national planning commissions, reforming civil service, leveraging information technology for governance, and fostering an integrated economy should be implemented.

An expert who prepared Nepal's first agriculture plan, Pradhan's analysis of the Planning Commission's role and duties sounds credible and convincing. He also emphasises the reform of the health sector.

One of the strong arguments he presented in the book is that students should not be engaged in politics, citing the wrong practice of student unions in Nepal. In a time when almost all students are aiming to go abroad, he suggests reviewing the student politics. He opines that the universities and educational institutions should be kept separate from politics.

The author says that the same applies to trade unions. He believes that the union has failed to fulfil its role as a professional organisation; rather, its strategies are expanding political domination. He opines that the work of the union is limited to the transfer and promotion of its employees and to covering up and protecting the irregularities of its employees.

The author explores Nepal’s natural resources, including biodiversity, renewable energy, and diverse climatic conditions. He also advocates for social audits to ensure transparency and accountability in development projects. He emphasises consensus-building among political parties to prioritise national interests over partisan agendas.

The book highlights Nepal's economic challenges, focusing on widespread poverty and low per capita income. It discusses the disparity between rich and poor and the failure of political leadership to address the economic disparities. It discusses how politics influence on every aspect of life in Nepal had hampered the country. It emphasises the need for honest political efforts to improve national development.

The image on the cover of the book is a symbolic one. Bees are known for their dedication to their duties. It always focuses on its duty only and does nothing other than its duty. If we applied the same quality within us, prosperity would be gained.

The book concludes with an optimistic note that achieving a conscious social order is possible through collective effort and commitment. By addressing fundamental issues like poverty, illiteracy, and unemployment, Nepal can unlock its potential as a prosperous nation.

(The writer is a founder of Orchid Books, Godar is a freelance writer.