- Thursday, 26 February 2026

Nutrition Insecurity In South Asia

South Asia still faces poverty, food insecurity, malnutrition, and diet-related non-communicable diseases. Across the region, progress in reducing malnutrition is uneven. The policies related to nutrition-sensitive agriculture and health are largely visible on the surface, but their implementation at the community level is not adequate and effective.

The limited availability, accessibility, and affordability of nutritious foods have profound impacts on the dietary patterns of local people and their nutritional outcomes. Therefore, we need a multi-sector approach to ensure all children, adolescent girls, and women in the region can get the nutritious foods, services, and healthy food environments they need to survive and thrive.

We continue to observe the region’s high climate sensitivity, air pollution, and erratic rainfall patterns due to climate change and environmental degradation. As a result, there is substantial loss of nutritional diversity, poor agricultural incomes, and food insecurity. The livelihoods of the majority of the poor, socially excluded, ethnic, and indigenous communities are more vulnerable to poor health and nutrition.

While there are several nutritional surveys and rapid assessments in understanding the health and nutrition status of communities in a particular geographical and socio-cultural context, there still lacks anthropological evidence on how nutrition is socio-culturally constructed in families and communities. The wider economic, political, historical, and psychological aspects of nutrition and food security are rarely explored and discussed in the social world of nutrition.

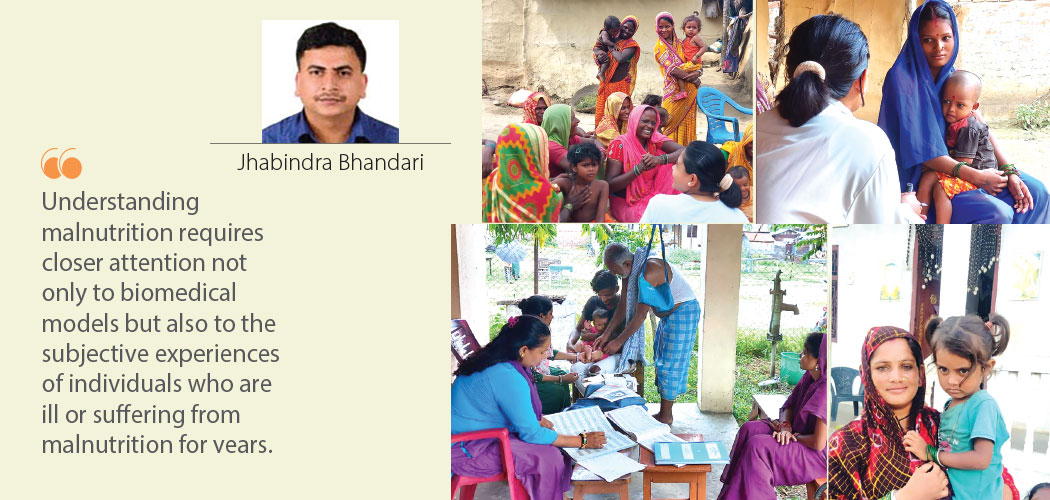

With the support from Action Against Hunger, an international NGO working in the area of humanitarian health and nutrition, among others, conducted an anthropological assessment of nutrition in selected communities of Siraha, Makwanpur, and Jumla. Our team of researchers trained in anthropology was engaged in fieldwork to explore how nutrition is shaped by social, cultural, economic, political, and historical factors.

More importantly, the researchers aimed to understand and document local perceptions, social systems, cultural norms, and meanings of nutrition in their everyday life. Besides, one of the anthropological enquiries was to explore how social hierarchies, marginalisation, local politics, and power structures influence people’s agency in accessing health and nutrition services in the communities.

In my team, Yojan Basnet and Kabita Chaudhary were the two young anthropologists who were curious to visit some of the rural and peri-urban areas of Siraha for ethnographic fieldwork that included observations, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, case studies, and participatory social and/or resource mapping. During the first week of August last year, the field research team visited the Sakhuwanankarkatti Rural Municipality of Siraha. In the rural areas, we had informal interactions with socially excluded communities such as Musahar, Chamar, Dalits, and other ethnic minorities.

In addition to socio-cultural and demographic contexts, the nutritional status of communities is heavily influenced by political and institutional drivers as well as economic and market systems. Understanding malnutrition requires closer attention not only to biomedical models but also to the subjective experiences of individuals who are ill or suffering from malnutrition for years.

The stories about illness and malnutrition are not just accounts of personal experiences but also reflect cultural values and beliefs about health and healing. Despite growing modernity and urbanisation, local people heavily rely on their local food products, indigenous knowledge, farming systems, and cultural practices of nutrition.

Nutrition policies and strategic interventions are poorly implemented in many communities. In our conversations with mothers from socially excluded groups, they have no idea where they get health and nutrition services. Nor do they have any clue about multi-sector nutrition plans and other nutrition-sensitive interventions that local governments have been implementing for years.

“This clearly reveals that our health and nutrition policies lack effective implementation at the local level. Obviously, the poor and socially marginalised communities are usually left behind. The relationships between local government officials and the excluded people at the grassroots are not always encouraging and trustworthy,” commented a social worker at the municipality. There is no clear communication from the offices of local government and hence a lack of transparency and trust in terms of how available resources are allocated and utilised for the benefit of marginalised groups.

A Musahar woman in her 20s with a malnourished daughter shared her frustration: “We usually do not visit the health facilities for nutrition services as we are not sure of getting full treatment and medicines.” It implies that still people do not have detailed information about the availability and accessibility of health and nutrition services in the communities.

Added she further, “Like my neighbours, I do not have land to cultivate crops and vegetables. My husband is in foreign employment. I do work on others’ farms for a livelihood. At the same time, I have to take care of my children and parents as well. This is an overwhelming responsibility as well as a challenging experience in my life. But what to do?”

However, health providers in the local health facilities argue that a few communities from rural areas still do not come here, though we have provisions for health and nutrition services. Perhaps some of the poor families cannot afford transportation costs and medicines if they have to buy them on their own outside. The family support system is also weak in the marginalised communities.

“Health facilities often face mounting pressure to deliver quality nutrition services. Due to inadequate human resources and limited supplies, the outreach clinics cannot be expanded in the remote areas. As a result, we cannot ensure timely follow-up and referrals for treatment of malnutrition in the rural areas,” said a health worker at the municipality. Moreover, there are no specific social protection services and safety nets for poor and vulnerable populations suffering from malnutrition.

On the other hand, the mobilisation of Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) and other community institutions is unfortunately inadequate. An elected representative at the municipality disclosed, “Because of the low level of health awareness, poor socio-economic status, limited water and sanitation facilities, and inability to access Healthcare in local health facilities, we need to specifically target socially excluded mothers and children for their immediate health and nutrition needs.” But it is easier said than done.

Thus, the ethnographic field research helped explore how knowledge about nutrition is differentially formulated, expressed, and disseminated within and across cultures. The cross-cultural variations in the nutrition narratives have deep appreciation for nutritional diversity. There is also a greater need to explore the social structure, customs, and kinship systems that shape food and nutrition behaviour in the communities.

More importantly, the anthropological insights to challenge inequity and social injustice are crucial, as the interplay between gender roles, cultural norms, economics, and language has profound implications for food and nutrition security. The power of culture in shaping food and nutrition behaviour is profoundly visible. Indeed, people communicate, perpetuate, and develop knowledge about nutrition from their indigenous food systems, community identities, and social relations.

(Bhandari is a health policy analyst and has an interest in anthropology.)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-original-thumb.jpg)