- Monday, 16 February 2026

Time To Shake Up Socialism

Socialism is not a new concept in Nepal. It became further pronounced after the current constitution mentioned it explicitly. 'Socialism-oriented economy,' 'socialism-oriented federal democratic republican state,' and 'to create the bases of socialism' are found in the present national charter.

Although socialism got constitutional recognition, the debate over it is continuous. What is the functional definition of socialism? Are we practicing it now, or is it the ultimate goal? If socialism is the destination, are there similar or different routes to reach it? Moreover, socialism warrants equally important discussion to determine whether it is an economic mode or a social fabric as well.

The new constitution that made Nepal a federal democratic republic put socialism on the centre stage despite having numerous queries surrounding it. Irrespective of the approaches to define and characterise socialism, the fundamental aspects like resources, their use and mobilisation, production, marketing, and their links to people and a country's income and economy are evidently essential.

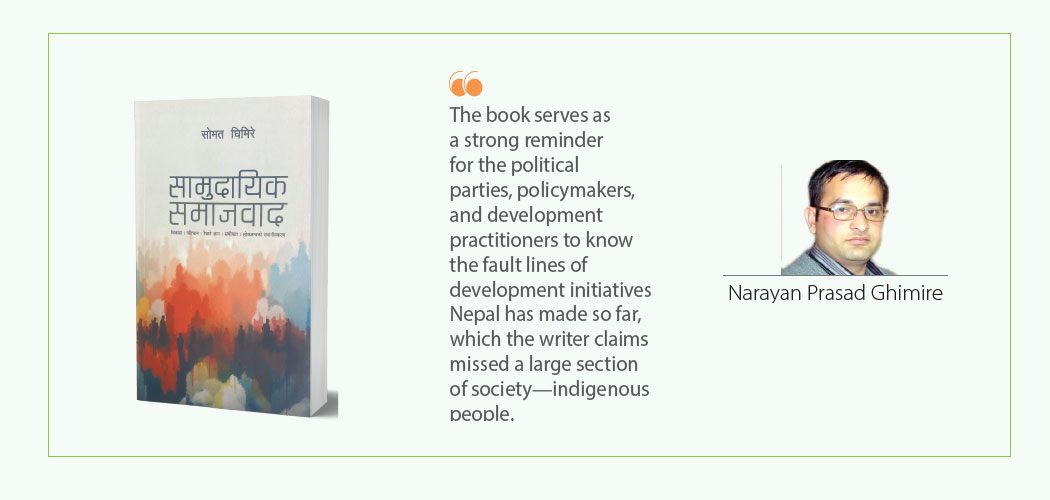

In this connection, a book, 'Samudayik Samajbad' (Community-based Socialism), penned by Somat Ghimire, is available in the market to seize attention. It is certain to draw the attention of our political parties and policymakers alike because it questions the present practices of 'socialism' and urges them to redefine it by keeping in centre the community and its concerns. In the very first line of the first chapter, writer Ghimire argues, "Socialism has already been corrupted in Nepal."

The 'isms' of different sorts advocated by different parties are blamed for having missed the boat of development, according to writer Ghimire.

The 252-page book talks in length about the indigenous people, their culture and cuisine, forests, agriculture, livestock and products, tourism, identity, development, federalism, and localisation of Loktantra.

Exposing the political slogans of different parties like 'Samajbad' of the Nepali Congress and 'Janabad' of communists, Ghimire asserts that their 'baad' (ism) nurtured the centre and failed to reach the community. "Socialism is not merely a pride and product of Singha Durbar. The state policies need to link diverse communities and youths to production. But Nepal's communities and youths are away from production," he reminds.

Although Nepal is said to be practicing the most effective form of governance, having three tiers of government where the local level is the government closest to the people and always ready to reach people's doorsteps, the way they are functioning is lacklustre. The book brings to light how the centre (federal) is still keeping hold of the sub-national governments.

In the wake of federalism, it was expected much that local resources would be identified and used wisely for their identity and economic strength with the free exercise of their rights, but they are scrambling to deliver on multiple fronts, including agriculture, tourism, and education.

The education and agriculture are so distant that they agriculture awaited the application of education, but the latter failed to internalise harmony. The same traditional concept of belittling agriculture before education is perpetuated by the local levels.

The writer also argues that Nepal's agriculture was labelled 'subsistence farming' and forced to move towards 'commercial farming,' which led to the extinction of the indigenous farming knowledge, skills, seeds, and varieties of species. The commercial farming, as he claims, promotes 'monocrop,' which saps the soil fertility.

The crop diversification and mixed crops were practiced in Nepal, keeping intact soil quality. Similarly, other problems in agriculture are revealed in the book: market-dominating farmers and value to their products, experts belittling farmers' skills, ignorance to diversification, overuse of chemical fertilisers, and grants usurped by political acolytes.

He also underlines the need for localising democracy by strengthening local governments. The author argues, "Despite exercising loktantra from a legal viewpoint following the political change, democratisation of our society is still elusive. It has limited loktantra to mere formality."

Retention of people in the village must be a priority, rather than worrying over the exodus of youths from the village and from the city to abroad, according to Ghimire.

He blames the practice of the present system and the past that they failed to pay heed to the diversity at local levels. From one province to another, there are different cultural, ethnic, and lingual setups that have their own ways of skills and knowledge generation. In the writer's argument, a centre-focused mentality is taking a toll on local government.

Similarly, he suggests the foundational governments, the local levels, not to replicate foreign models hastily but to focus on promoting their own identity. Once local resources can be used wisely and uniquely, it evidently helps build identity.

Ghimire even suggests developing ethnic towns and cities. "Big or small, the cities are regarding Kathmandu as an ideal city. Why can't there be a city reflecting Kirat culture? Why can't we have a city depicting Tamang civilisation? Now, the local governments should focus on the diversification of city/town building, and it can be realised where possible."

Throughout the book, the presentation of arguments is incisive, while language is sometimes pejorative. Writer Ghimire brings references of his field visits, the concern shown by the locals during conversations, and research findings. It not only enlivens the book but also touches the base and gives an academic lens. The views presented from the horse's mouth give the journalistic feature to the book.

The extensive time he spent with the indigenous people in different parts of the country built knowledge on their culture, lifestyle, upbringing, food and cuisine, forest, and farming.

The book serves as a strong reminder for the political parties, policymakers, and development practitioners to know the fault lines of development initiatives Nepal has made so far, which the writer claims missed a large section of society—indigenous people.

At a time when federalism is celebrated much as the system to reach people's doorstep and forward development activities with extensive participation of people, there is much more to correct in the present practices of three tiers of government so that a solid foundation for economic prosperity can be set up.

The areas to revisit as per his suggestions are agriculture, forests, land, tourism, education, political parties, and their organisations.

(The author is associated with Rastriya Samachar Samiti.)