- Thursday, 30 October 2025

Democracy Day

Revolutions That Empowered Women

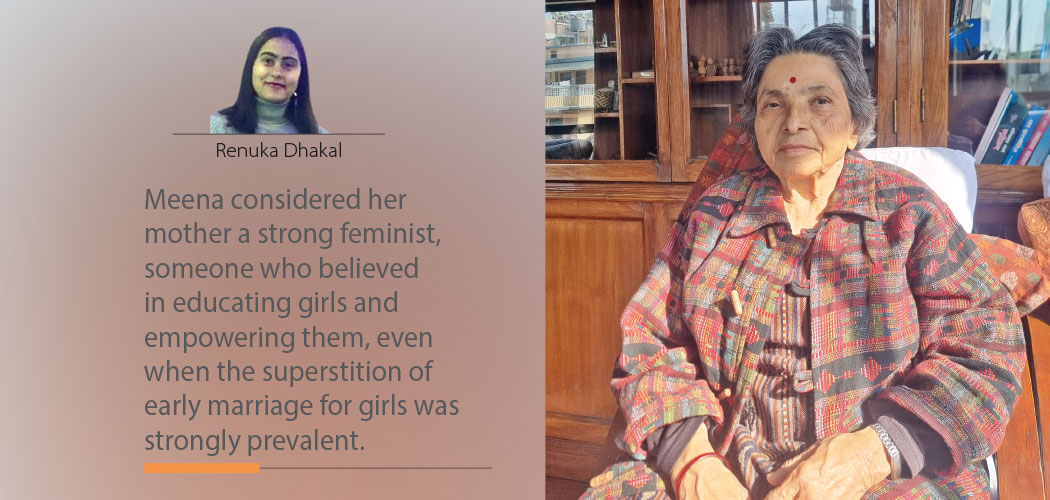

Meena Acharya, who played a pioneering role in empowering Nepali women, has witnessed many ups and downs of Nepali politics spanning almost seven decades. Daughter of Tank Prasad Acharya, who was known as a living martyr, Meena grew up amidst the political tumults that resulted in 1951 revolution, also called Sat salko kranti, as it occurred on Fagun 7, 2007 B.S.

Meena was 13 years old when the revolution rocked the nation, overthrowing the 104-year-long despotic Rana rule. She still has vivid memories of the various political activities against the Rana dynastic regime. “I used to walk behind my mother, distributing books in schools and handing out newspapers and pamphlets,” she recalls, talking to this daily. Despite being a teenager and not fully politically conscious, she somehow participated in the pro-democracy activities innocently.

Tanka Prasad Acharya formed Nepal Praja Parishad in 1936 with the goal of removing the autocratic Rana rule. Four great martyrs Shukraraj Shahstri, Dharma Bhakta Mathema, Ganga Lal Shrestha, and Dashrath Chand Thakur belonged to this party. She still has a faint memory of the days when the four democratic fighters attained their martyrdom. Her father was not executed as he belonged to the Brahman caste. Following their killing, hundreds of youths, who raised their voices against Ranas, were imprisoned for varying lengths of time.

Days of hardships

After her father was sentenced to life imprisonment, her family was torn apart. “The Rana regime confiscated everything from our house. It did not spare even food from utensils. Then my mother took me and my sister to my maternal uncle’s house in Dhanusha,” she says.

Later, her grandfather took her to Banaras, India, where they stayed for two years. After returning, she continued her studies at the local village school in Sirsiya. After her grandfather passed away, her mother moved to Kathmandu in 1948, rented a home, and enrolled her in Gausala School to continue her formal education.

After Tanka Prasad Acharya was freed from prison, Meena was sent to Gandhi Ashram School in Rajasthan, India. Later, she enrolled in Padmakanya School and completed her intermediate studies. She did her bachelor's degree in economics from Delhi. Later, she went to the Soviet Union for further studies and earned a master's in economic cybernetics from Moscow State University. She returned to Nepal in 1966 and joined the Research Department at Nepal Rastra Bank. She completed her PhD in Development Studies from the US in 1987.

She tied a nuptial knot with a Russian citizen. She returned to Nepal with her husband and a daughter. She states that at the time when a woman married a foreigner, she would lose her Nepali citizenship automatically. She had to fight to regain her Nepali citizenship. However, after 10 years of marriage, they got divorced, and she began her life anew in Nepal.

As a towering intellectual with dozens of books to her credit, Meena has also carved her identity as a political activist, feminist, economist, researcher, author, and consultant. She served as the senior economist at Nepal Rastra Bank and an advisor to former President Bidya Devi Bhandari. Her research works cover the topics of development, economy, gender issues, foreign aid, the labour market, politics, poverty, and so on. Here, recent books include Centring Women in Nepal’s Economy and Society Vol. 1 and 2 and Swatantrata Ra Samanatako Nirantar Yatra.

Then and now

She states that when her father became the Prime Minister of Nepal in 1956, there was no corruption at that time. Leaders sacrificed their lives for the cause of the nation. Although she was the daughter of a prime minister, she did not enjoy any privileges from the state. I walked down from Kupandol to Padmakanya School just like the children of ordinary people.

But now, she is quite dissatisfied with the current political scenario, as the leaders are more involved in corruption than in the development and progress of the country.

“It seems today’s politicians often indulge in money and power politics,” she vents her feelings when asked about the current politics.

She adds, “Any change moves us forward, not backward. As changes amplify, challenges also grow. With change, many issues have emerged. In the past, freedom of expression and the freedom to read and write were important, but now, different kinds of issues are arising.”

She started taking an interest in politics quite late. She began her political journey after retiring from her job in 1990. She tried to revive the Nepal Praja Parishad but couldn’t succeed and eventually left politics. Even her siblings didn’t like being involved in politics, as they had already seen the huge struggle during her father’s political movement.

Meena perceived her mother as a great woman whose endurance during that time was a symbol of women’s empowerment. “My mother didn’t have time to interact with her father. When I was around 3 years old, my father was taken to jail.

She witnessed her mother’s struggle as the wife of a revolutionary leader, a dedicated daughter-in-law, and an enduring mother who raised her children in a time when survival was difficult. When Meena was nine years old, her father, who was in jail, became concerned about marrying her off. But her mother wrote a letter to her husband, stating that such practices were no longer necessary in the modern era and parents focus should be on educating their daughter and making her independent.

Meena considered her mother a strong feminist, someone who believed in educating girls and empowering them, even when the superstition of early marriage for girls was strongly prevalent. Meena is now pleased to see the progress of women. She has published many research papers and books on women. She remembers that the feminist revolution began during her time.

She thinks that today's economy is based on technology. “Earlier, Nepal’s economy was based on farming, but now the economy is based on technology and is gradually improving.” When she joined Nepal Rastra Bank, she was the only woman in a senior position.

She has been living at home for five years, reading books, yet many people still visit her home to talk and conduct interviews. Even though she doesn’t frequently go outside, she still has the energy to learn and encourage others.

(Dhakal is a journalist at TRN.)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-square-thumb.jpg)