- Sunday, 1 March 2026

Wildfires: Growing Environmental Threat

The year 2024 marked a grim milestone in the battle against climate change. The temperature of the Earth crossed 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels for the first time in recorded history, bringing the world even closer to the threshold beyond the targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement. This does not just denote a number in a report but a warning that shows looming havoc threatening the one world that we all share. The report provided by the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) shows that climate change has forced temperatures on the planet to levels never seen before. As a result, wildfires are also manifested as one of its most devastating impacts. The rise of temperatures, dried-out vegetation, changing weather patterns, and prolonged droughts have created a mixed combination that allows for fire to ignite and spread.

These fires are no longer isolated to a specific area but have marked their scar across the globe, from the foothills of the Himalayas in Nepal to the Hollywood Hills of California.

Global impacts

From the vast boreal forests of Canada to the eucalyptus groves of Australia, wildfires are a growing threat exacerbated by climate change. The 2024 wildfire season in Canada was the worst record that the country experienced, with nearly 13,290,000 acres consumed and affecting air quality in the United States (US) as far away as New York and Washington, D.C., being noticeably affected. The National Interagency Fire Centre (NIFC) in the US recorded more than 51,320 wildfires that burnt an estimated 8,142,689 acres in that same year. The recent 2025 Southern California wildfire, which was exacerbated due to extreme heat and Santa Ana winds gusting up to 40-50 mph, created a perfect storm to intensify and spread the fire over 57,000 acres with multiple wildfires, notably the Palisades, Eaton, and Hughes fires. This could be the costliest wildfire in US history, with economic losses estimated to be between $250 billion and $275 billion. Similarly, Australia suffered the 2019-2020 bushfire season, known as the 'Black Summer,' where millions of hectares were burnt down, leading to severe ecological and financial loss and a radical reduction in biodiversity. The country is still recovering from the aftermath of the incident. These multiple incidents underpin the growing reality of challenges faced even by the best-equipped nations in taming wildfire risks in a world heating up fast.

Wildfires in Nepal

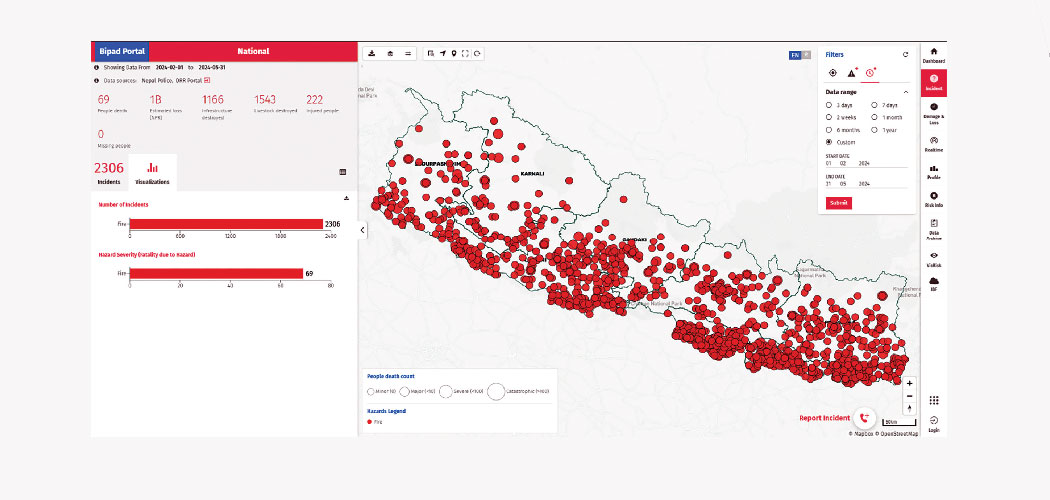

Around half a world away, in the global south, Nepal’s story feels eerily similar. From March to May, the areas are dry, heralding the beginning of the forest fire season. This too has intensified through the years. An estimated 200,000 hectares of forest area are lost to fire every year in Nepal on average for the last 18 years. Limited rainfall during the winter and early pre-monsoon periods increases the vulnerability of dry vegetation to catching fire. Hot and windy conditions from March to May create optimal environments for these fires to spread rapidly, particularly in hard-to-reach areas. During the peak fire season, Kathmandu frequently ranks among the most polluted cities due to smoke and haze. The 2021 wildfire season in Nepal is considered the worst wildfire year in history, with over 6300 wildfires—10 times greater than the average of 2002–2020. This rich forest, covering almost 40 per cent of the land in Nepal, can disguise itself as a blessing and a curse at the same time. According to recent data, there have been 2,700 forest fire incidents reported during the pre-monsoon season in 2024 alone. This has exacerbated air pollution and has threatened vulnerable communities residing in the area that are frequently affected by these fires. The significant research gap in understanding the specific causative parameters and impacts of these fires on Nepal's local biodiversity and carbon emissions underlines the urgent need for focused studies and targeted interventions.

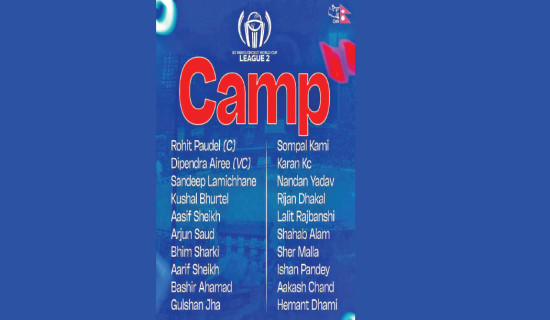

Figure 2: BIPAD Portal interface visualizing 2,306 reported forest fire incidents in Nepal from February 1, 2024, to May 31, 2024, along with associated fatalities and hazard severity, based on reported data from Nepal Police and the DRR Portal.

Wildfire management

At present, the management of wildfires is largely reactive in the global context, focusing on extinguishing fires after ignition has already occurred. This practice inevitably compromises other proactive strategies that could be taken to prevent the starting or uncontrolled spread of fires. Advanced technological tools, including geospatial technologies and machine learning techniques, can predict and prevent fires. These tools are currently being used in a very reactive way, with the applications being largely confined to response, recovery, and damage assessment after a disaster has occurred.

For instance, NASA's Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) and the Fire Information for Resource Management System currently provide global data on fire detection, while the Sentinel satellites of the European Space Agency provide detailed imagery. However, with infrequent revisit times and sensitivity to cloud cover, such systems may be slow to detect fires, which greatly reduces their real-time utility. A shift from reactive to proactive strategies is essential to enhance wildfire management anywhere in the world.

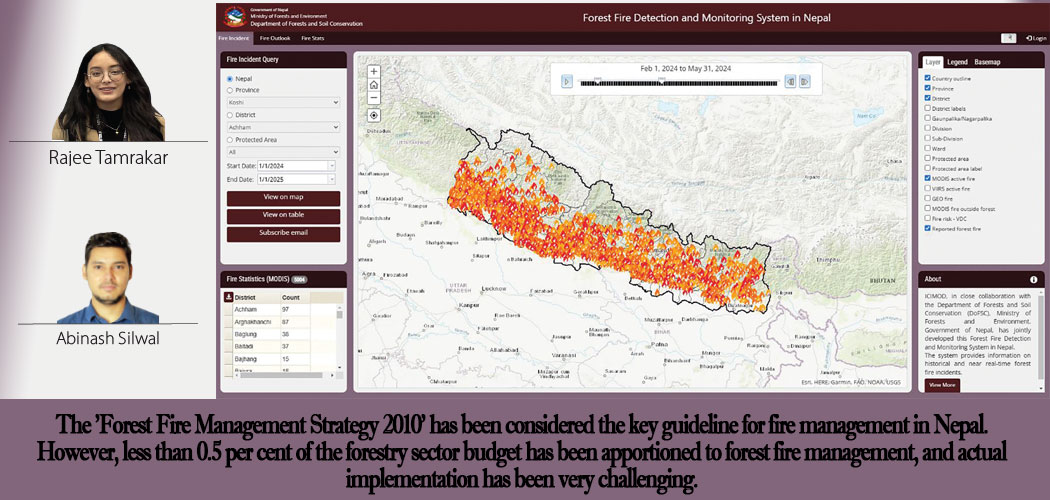

Nepal has made significant progress in integrating geospatial technologies into the management of forest fires. Specifically, the Forest Fire Detection and Monitoring System of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Developments, in collaboration with the Government of Nepal's Department of Forests and Soil Conservation, gets satellite data from MODIS and VIIRS sensors of NASA for near real-time information on incidents of forest fires. This will provide the right mapping of fire-prone areas, hence enabling early detection and monitoring of wildfires across the nation. Even though these technologies are biased toward a reactive approach, it does help contain the spread of fire. In addition, the Community-Based Forest Fire Information System supplements this by engaging local communities in reporting fire incidents. This two-way communication system allows community members to receive alerts about nearby fires and report new incidents, enhancing ground-level responsiveness and fostering community engagement in wildfire management.

Further, the web-based Building Information Platform Against Disaster (BIPAD) portal developed by the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) of the Government of Nepal acts as an integrated Disaster Information Management System (DIMS) in Nepal. It captures data regarding different hazards, including forest fires, which are useful in disaster preparedness and response. Access to data through the web portal allows sharing in government agencies, NGOs, and community-based organisations to help hazard management at the grassroots level.

While there have been advancements, the path to fully integrating these geospatial tools remains challenging. To make wildfire management effective in Nepal, the priorities should be increasing data sharing between agencies, enhancing real-time data processing capabilities, and expanding community training programs. Nepal needs to leverage these technologies to bridge prevailing gaps and make it resilient against ever-increasing wildfire threats.

Way forward

Addressing this growing risk, Nepal should focus on a multifaceted approach including a merger of global technological advances with a localised, community-oriented solution. This involves priority investments by the Nepalese government in early warning systems, strengthening policy frameworks, and scaling up available technologies and institutional capacities. The 'Forest Fire Management Strategy 2010' has been considered the key guideline for fire management in Nepal. However, less than 0.5 per cent of the forestry sector budget has been apportioned to forest fire management, and actual implementation has been very challenging. The process of reducing fire risk has been slow due to a lack of financial and political support. Investment in satellite surveillance and drone reconnaissance technology needs to be increased to improve real-time monitoring and response. This calls for the establishment of district-level fire management units with experts to effectively manage these cases. In this regard, the approach at the community level must be at the core of this strategy. Often, the local communities are the first line of defense against wildfires, and engaging them will do much to enhance preparedness and response. The establishment of public education campaigns is equally significant in the light of keeping local communities informed of fire prevention techniques and the operation of fire breaks.

The traditional reactive approach to fire management—waiting for fires to start before responding—is outdated in today’s context of rising temperatures and extreme fire behaviour. Nepal must shift to proactive strategies that combine technology, policy, and community involvement. All these challenges and the continued surpassing of warming beyond the 1.5-degree threshold have made us rethink our approaches. The question is no longer whether we will have the technology to track and predict fires—we have it. The challenge now is between capability and access, between what is possible and what is available. As the world is getting hotter, the question should not be if we can develop advanced fire-fighting tools but whether or not we would be able to give these to those who need them before the world burns. For Nepal, this is not just about protecting the forests but also natural heritage and means of preserving biodiversity for future security. Bridging the gap between capability and access is a need and also a moral obligation to meet the challenges of climate change.

(Silwal is a graduate research assistant at the University of Kansas, USA and Tamrakar is a graduate teaching assistant at Southern Illinois University.)