- Friday, 20 February 2026

Climate Change Impact On SRHR

Climate change has a global impact on public health, economic, humanitarian, and gender equality. Increasing temperatures, sea-level rises, changing patterns of precipitation, and more frequent and severe extreme events have adverse effects on key determinants of human health, including clean air and water, sufficient food, and adequate shelter. It results in increasing heat stress, malnutrition, communicable and noncommunicable diseases, and facilitating the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, contributing to health emergencies. Climate change and air pollution worsen each other, resulting in cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Alahmad et al., 2023). A growing number of studies also suggest that rising temperatures can impair mental health and increase the risk for suicidal behavior. It is estimated that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause 250,000 additional deaths per year due to malaria, malnutrition, diarrhoea, and heat stress (WHO). The 2022 Lancet Countdown highlights that the vulnerable communities, particularly those in low-income regions, are disproportionately affected, leading to increased health risks and reduced access to healthcare services.

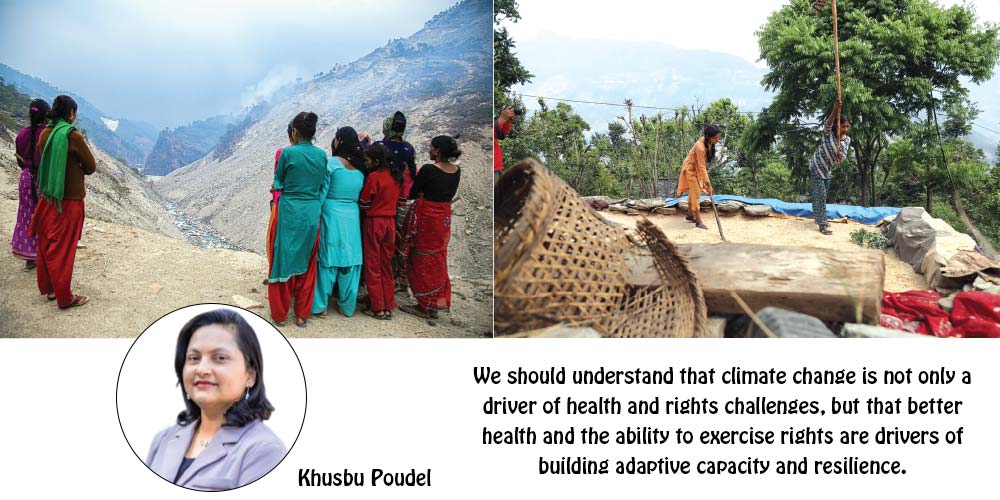

In recent years, climate change, gender, and sexual and reproductive health and rights have been linked to each other. Women, girls, and marginalised communities are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis because they lack power. In effect, climate crises deny women the ability to control their own fertility and to plan for their futures (Ipas). The U.N. estimates that women and girls account for 80 per cent of the people displaced by climate change, leading to severe implications for those requiring maternal health services. There are about twice as many maternal deaths in conflict-affected and fragile settings compared to stable settings (2021). There is a direct link between environmental pressures, gender-based violence, and unwanted pregnancy (IUCN). Women and girls’ need for sexual and reproductive health care/abortion services increases, but in times of disaster, those services are likely to be disrupted. Women face significant challenges in accessing maternal and reproductive health care services during and after climate-related disasters such as floods or earthquakes due to displacement, limited access to health care facilities, and interruptions in medical supply chains. A study conducted by Ipas Nepal in 2022 shows that women and girls’ experiences during extreme weather events often include increased care work, difficulty evacuating safely and in time, heightened exposure to GBV, and poor health outcomes for menstruating girls, pregnant women, and their children.

The impacts on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are further exacerbated by gender and social inequalities. Women and children are often forced to leave their homes, making them more susceptible to violence and abuse. In addition, as resources become scarce, women and girls must travel further to collect necessities like food, water, and firewood, which increases their risk of exposure to sexual abuse, physical abuse, and harm. Women play pivotal roles in climate adaptation and mitigation efforts, yet their contributions are often undervalued or overlooked.

Challenges in SRHR

The current methods for resourcing responses to the impacts of climate, environmental, and other crises are not adequate, as all the institutions and mechanisms work in silos. Similarly, the conventional health sector responses are not equipped to manage the multiple, interconnected challenges health systems face in the climate, economic, humanitarian, and other crises. Health systems are expected to navigate the impacts of the climate crisis without political prioritisation, feminist financing, and climate action that responds to the gendered components of the crisis. During climate-related disasters, the health system's capacity to provide SRHR services is often hindered, which further limits women and girls' access to the necessary health services. There are existing myths, norms, and values in society regarding SRHR and climate change that make it more vulnerable during climate emergencies. Climate and health financing is not adequate.

Ways forward

As a way forward, we must invest in health, including reproductive health, as an integral pillar of climate resilience and adaptation at the individual and community level, particularly in vulnerable communities, fragile settings, and humanitarian contexts. Political leadership and willingness within the government to address the SR health risks of climate change. Enhancing the capacity of the health workforce so that they can deal with the SR health risks from climate change. Conduct climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments for health policy and programmatic planning.

Ensure that national adaptation plans explicitly address health risks and vulnerabilities, including SRHR. Building evidence at the intersection of climate change and SR health to support decision-making to mitigate climate-induced health impacts. Stockpiling of SRH commodities and considering women’s and girls’ needs when building spaces for shelter and resettlement during and after climate disasters. Promoting health policies and programs in sectors such as agriculture, transport, forest, environment, water, housing, and energy can lead to reduced health risks and improved environmentally sustainable health practices, behaviours, and processes.

Improve access to health care, particularly sexual and reproductive health care that is resilient to a changing climate. As women and girls are effective actors or agents of change, it is important to involve them to develop and lead climate action efforts that include reproductive health. Invest in women’s and girls’ education and reproductive autonomy to give them more power over their own lives and decisions. Ensure the needs and voices of vulnerable populations are heard and addressed in climate negotiations. Increase women’s opportunities for decently paid work, so they don’t have to resort to jobs that risk their health and safety.

We should understand that climate change is not only a driver of health and rights challenges, but that better health and the ability to exercise rights are drivers of building adaptive capacity and resilience.

(The author is a programme coordinator, climate justice, gender, and SRHR at Ipas Nepal.)