- Wednesday, 4 March 2026

Public Land Encroachment: A Challenge To Authorities

Encroachment and land grabbing on public lands have become the biggest worries in our country. Public land is illegally occupied, used, or appropriated by an individual, persons, or institution, which has created considerable difficulties in terms of governance, socioeconomic development, environmental sustainability, and social justice. Land encroachment can happen when people settle in, build their houses and properties, or engage in unauthorised activities such as farming or businesses on public land, including forests, river banks, parks, and other vacant government spaces.

Land mafias, business personnel, political representatives, and public figures are often at the forefront of land grabbing, which is a more aggressive and systematic form of encroachment. The act of appropriating public land for personal purposes, known as land grabbing, entails the use of force or legislative fraud, corruption, and a range of other strategies. Reports claim that after former rebels joined mainstream politics, the incident of public land encroachment in the name of providing relief to poor landless people has gone up many folds.

Illegal settlements in near or in public spaces such as roads, forests, parks, and river banks and grabbing of land regarded as lucrative have taken place in our nation. The land scams such as Lalita Niwas, Giribandhu Tea Estate, Nepal Scout properties, and illegal settlements near big and small rivers within the Kathmandu Valley and other areas are some of the biggest incidents of public land capturing for individual benefits. Authorities found difficulties in dealing with such land scams as well as illegal settlements.

Against this backdrop, the Supreme Court (SC) issued a decision on December 3, 2023, enforcing a 20-meter buffer zone on both sides of riverbanks in the Kathmandu Valley, giving rise to widespread concern and confusion. The decision aimed at protecting rivers and reducing encroachment has left home and property owners, potential builders, and local governments worried about its implications. Although based on principles of environmental preservation and disaster mitigation, the ruling raises serious doubts about its practicality and the socioeconomic consequences for thousands of people.

The Supreme Court’s decision underscores the urgent need to address these issues. It specifies that construction within 20 meters of riverbanks is not allowed—double the previously allowed setbacks. The ruling also grants the government the authority to gain land within these limits, subject to existing regulations and compensation guidelines.

However, implementing this judgement is fraught with challenges. The financial implications, for instance, are staggering. If enforced, the government would need to compensate property owners for over 100,000 structures, costing the nation a substantial amount of money.

Following the verdict, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) issued a notice prohibiting development within the newly mandated 20-meter zone. However, this warning has caused panic among residents, who now fear that the KMC will demolish their homes or seize their property without notice. For example, the notice does not outline the land acquisition or compensation process, leaving residents uncertain about their future. Mayor of KMC, Balen Shah’s decision to demolish illegal structures built on public property has reignited a crucial debate about chronic encroachment on public land nationwide.

Challenges

Implementing the SC verdict effectively is full of doubt as it has additionally raised public policy issues. The CPN-UML said the decision is against the Nepali citizen rights on land and jeopardises the lives of tens of thousands of people.

Public land infringement is evident in places like the Kathmandu valley and the Terai regions. With the development and growth of urban structures, roads, pathways, river banks, and even historical structures are being occupied for private and commercial purposes. In the Terai region, infringement into public land for agriculture and urbanisation is a key reason while river and stream banks are invaded. Some examples of illegal occupation involve putting up commercial structures and erecting buildings on public properties like historical ponds, woodlands, and roads. Settlements near the riversides and allotting public properties for the industrial sectors worsen the situation, resulting in degradation of the geographical and historical identity of these areas.

Public property has to be preserved for the public and the environment, but the desire to make profits overrides all that. Unfortunately, this invasion is decreasing the availability of open spaces in cities like Kathmandu and elsewhere. Although the legislative provisions of Nepal have strong measures to preserve the public land, the governmental and non-governmental actions to enforce these measures are quite negligible. The Land Revenue Act 2034 BS, the Land Measurement Act 2019 BS, and the Civil Code 2074 BS define public land under multiple acts of legislation. Also, it mentions the responsibility of various governmental and non-governmental institutions.

These guidelines define the public land to include the following locations: roads, wells, ponds, temples, parks, forests, and any other social places. Section 300 of the Civil Code 2074 BS stipulates that the district-level administrative or local governments are responsible for the protection of the above-mentioned areas. The regulations in the Local Government Operation Act 2074 BS have allowed provincial administrations to prevent the use of public land by stopping the construction of physical structures and encroachment.

However, preserving the public spaces has not always been effective because of the failure in the implementation of relevant laws, which led to the loss of a substantial part of public areas over the years. Government employees who intend to benefit from the sale of a public estate are among those involved in the illegal registration of government land as private properties. A lack of political willpower in handling this vice has made it even more difficult to reclaim the encroached lands.

Role of local governments

As per the Local Government Operations Act, local governments are to safeguard public properties. Nevertheless, their ability to contain land encroachment has been poor, with many organisations lacking the capacity or commitment to implement land laws. The recent activities initiated by the KMC under the leadership of Mayor Shah are quite encouraging, yet these initiatives also emphasise the role of the provincial governments. The system of federalism that governs Nepal has decentralised the authority of governance, and thus, local governments have the major role of safeguarding public land. Still, it also calls for increased cooperation and involvement from provincial and federal governing bodies.

In a situation where the government is taking back areas that have been grabbed, it should be very clear and fair in handling compensations. This has to do with such aspects as increasing the compensation sums and ensuring proper assistance to the owners of the concerned properties. For the protection of public lands, a cohesive national policy on the same matters significantly in the nation. This policy should be developed in collaboration with all levels of government and include clear guidelines for local authorities on how to effectively combat land encroachment.

Technology, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and digital land registries, can aid in managing public lands and preventing invasions. Additionally, public education on the importance of protecting public land and the legal consequences of invasion is crucial.

Landless squatters’ problems

However, the problem of landless squatter colonies on public land, especially in Kathmandu Valley, has further fuelled public property invasion. With reference to the state-led implementation of neo-liberal restructuring, the KMC often tries to evict landless squatters living in the riverine areas of the Kathmandu Valley. In every region of India, people have settled themselves in government lands. This problem does not only exist in occupied public land; it also entails the removal of people from squatter structures. Since the problem of landless squatters is more or less a political one, it also has implications for social justice and economic suffering. Politicians and political parties are invariably seen to mobilise people to put tents on the piece of land under the guise of eradicating poverty and landlessness.

One of the reasons that have not been solved sufficiently by the state is at the centre of the issue, which is the issue of landlessness. Politicians and planners have over the last four to five decades abandoned these vulnerable groups, hence resulting in their marginalization. Therefore, finally, controlling this menace of slums and landless people has emerged as a crucial issue for political parties, communities, and the government.

Another critical issue that faces policymakers on how to address the problems of slums is how to identify the eligible landless squatter. While laws such as the Land Act 2021 establish terms such as ‘landless Dalits,’ ‘landless squatters,’ and ‘disorganised settlers,’ the stakeholders and the regulatory bodies turn around and define/apply those terms in a more liberal way depending on the circumstances. This has remained the case till today due to these ambiguities, thus leading to confusion when handling this problem.

Political patronage by those in power has also aided this in the region. The powerful people often compromise on the development of slum areas. Some people politicise and allocate land for landless squatters and thus help develop slum settlements, aggravating the problem. The Nepali government has formed 22 commissions on land problems, but the condition persists.

Negative impacts

Encroachments and takeover of public lands is a phenomenon that has various impacts on governments and society. Authorities cannot collect potential revenues through land taxes and fines. They can get revenue by leasing the occupied public spaces. This loss hampers the government in meeting its commitment towards funding public services and development programmes. Encroachment has led to haphazard urban growth, limited public services, and congestion.

The act of acquiring a large chunk of land exacerbates social-economic injustice by displacing vulnerable individuals, indigenous communities, and urban poor most of the time. Disputes over encroached or reclaimed land often create conflicts between communities, encroachers, and authorities. Such conflicts affect society, causing social instability.

Encroaching upon public land or grabbing such property leads to the destruction of the environment and increased sensitivity to calamities such as floods and landslides in forest and wetland prone areas. Improper city planning and encroachment result in urban growth, leading to pollution, limited green space, and poor living conditions. Meanwhile, manipulation of land acquisition by corrupt officials weakens the confidence of citizens in their governments. This lack of confidence poses a threat to the government’s legitimacy and the Common Law Fund. These acts reveal a country’s vulnerabilities in defending its land, necessitating land governance reforms, anti-corruption measures, and increased transparency and accountability.

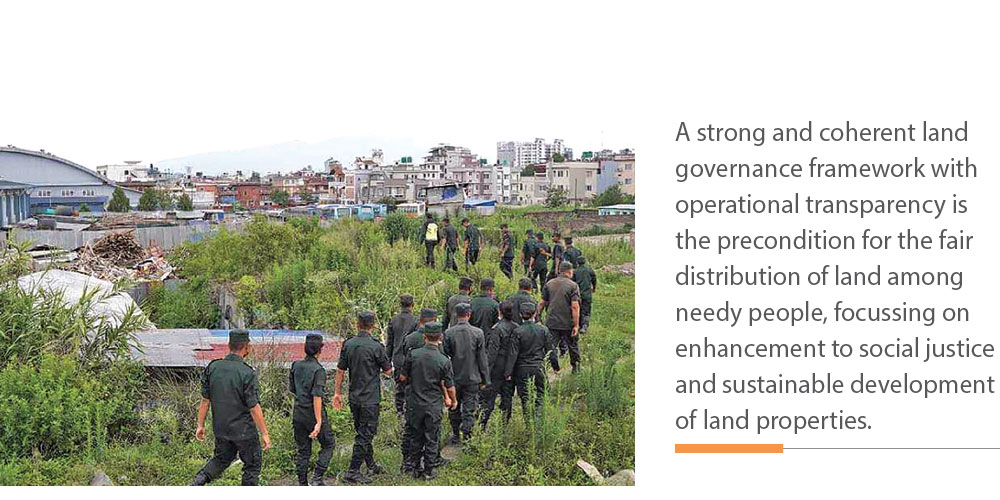

Experts recommend some solutions to these issues. They believe the public land encroachment and grabbing requires gradual changes in legislation, institutions, anti-corruption initiatives, and people’s participation in protecting public properties. A strong and coherent land governance framework with operational transparency is the precondition for the fair distribution of land among needy people, focussing on enhancement to social justice and sustainable development of land properties.

(Upadhyay is a former managing editor of this daily.)