- Saturday, 7 February 2026

Preserve Traditional Housing With Thermal Comfort

Nepal, a geographically landlocked country situated between India and China, features diverse climatic and geographical variations. The country is broadly classified into three ecological regions, extending from east to west. Climatic features across these regions can be observed within a short distance from south to north, over a span of 193 kilometres. The Northern Mountain, Middle Hills, and Southern Terai regions are characterised by cold, temperate, and subtropical climates, respectively.

Each region exhibits distinctive housing patterns, cultural differences, and adaptive behaviours to mitigate thermal discomfort. Traditional construction skills, which aim to improve indoor thermal conditions, have been passed down through generations with minimal modification. However, these methods are increasingly being replaced by contemporary construction practices, including modern designs and artificial materials.

Every year, new houses are built in Nepal as part of urbanisation and modernisation. In this context, it is important to understand the state of thermal comfort experienced by Nepali people living in traditional (Moulik Raithane) homes, which have influenced local culture. The architectural styles also vary significantly from south to north and east to west, reflecting differences in climate, culture, and ethnic origins of people. While neighbouring countries like India, China, and Pakistan have established their own thermal comfort standards, the Nepali government is yet to implement such standards.

It is the right time to ponder questions like why our ancestors built houses according to climate and region, why are wooden houses with thin walls common in the Terai region while stone houses with thick walls are prevalent in the mountainous and hilly regions, and how appropriate it is to replace traditional houses with modern constructions.

Good indoor environment is equally indispensable for the success of buildings, both for resident comfort and economic efficiency of energy consumption and sustainability concerns. According to ASHRAE Standard 55 (2013), thermal comfort is defined as “the condition of mind which expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment.” Thermal comfort standards are necessary for building designers and engineers to provide indoor environments that occupants find comfortable.

Researchers such as Nicol, Humphreys, de Dear, Brager, Rijal, and Gautam have highlighted that thermal comfort is greatly influenced by perceptions, expectations, and opportunities to adjust clothing levels and indoor environments. Hence, our recent research into the conditions, merits, and demerits of 'Moulik Raithane Ghar' in different climatic regions of Nepal can be a solution to develop rational policies and plans for the future of this pressing concern.

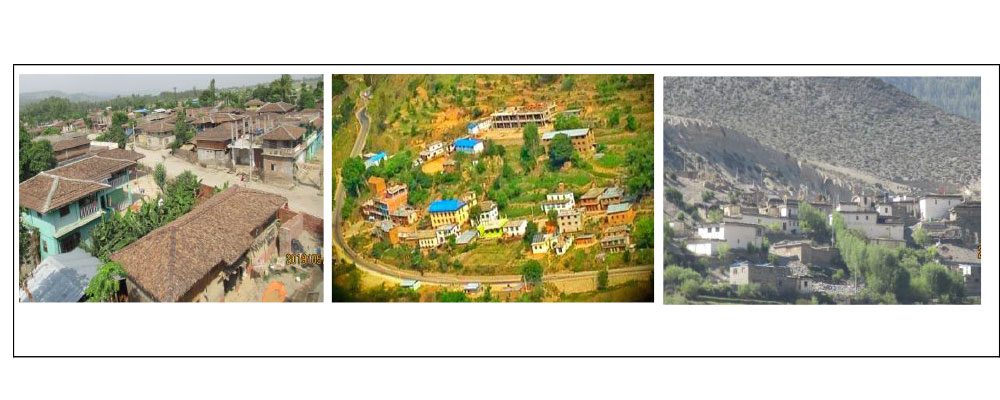

The study areas were selected based on altitude, climate, and housing type. Three climatic regions were selected: Mustang (Thini) in the cold region (Himalayan, altitude 3000-8848 m); Kavrepalanchok (Katunjebesi) in the temperate region (Hilly, 600-3000 m); and Sarlahi (Hariwon) in the subtropical region (Terai, 60-600 m). The field survey was conducted in winter 2016 and summer 2019. Figure 1 shows the study areas of respective regions.

The outdoor air temperature is highest in the sub-tropical region (Sarlahi district), middle in the temperate region (Kavrepalanchok district), and lowest in the cold region (Mustang district). Among all investigated areas, mean outdoor air temperatures were maximum in the months of May (32 ºC), August (26 ºC), and July (18 ºC) for Sarlahi, Kavrepalanchok, and Mustang districts, respectively. The differences in monthly mean outdoor air temperature between the maximum (highest) and the minimum (lowest) were identical by 13 °C to 15 °C.

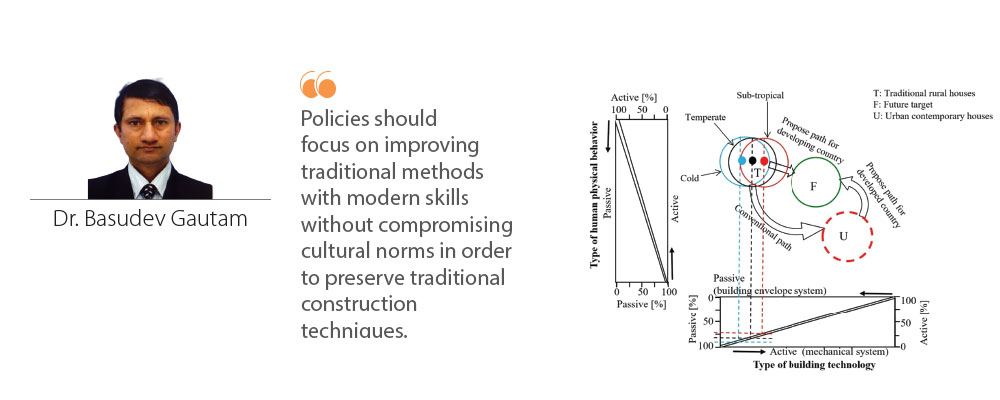

Figure 2 shows a schematic relationship between the types of built-environment technology and associated human behaviour in different regions. The horizontal axis represents technology, while the vertical axis represents behavior. The left extreme of the horizontal axis indicates cases with local traditional passive technology alone, while the right extreme represents cases equipped fully with active technology.

Traditional passive technology requires very active behaviour from people to restore indoor thermal comfort, whereas active technology requires less passive behaviour since it theoretically handles everything. In this diagram, the current condition of traditional houses and their lifestyles are positioned in area “T,” where it is challenging to maintain sufficient indoor environmental conditions with old and poor building envelope systems alone.

People need to engage in various behaviours to avoid thermal discomfort. Area “T” includes three circles with dots representing the condition of traditional houses in cold, temperate, and subtropical regions, with 95.4 per cent, 86.8 per cent, and 74.8 per cent of traditional houses in these regions, respectively. Contemporary houses with mechanical systems for heating and cooling, especially in developed countries, are positioned in area “U,” where people may be less active in managing their comfort.

In both areas “T” and “U,” there may be issues with optimal health since active systems may provide insufficient opportunities for occupant behaviour, while passive systems alone may require too much. Shukuya (2013) suggests that understanding how people restore their thermal comfort in traditional houses by changing clothes and engaging in other activities can guide future approaches. Extracting the positive aspects of traditional lifestyles and incorporating them into future living standards could be beneficial.

Some significant regional differences exist in indoor air temperature, comfort temperature, preferred temperature, and clothing insulation in winter. People living in Nepali traditional houses tend to achieve thermal comfort by adjusting their clothing according to local climate and building conditions. The context clarified in this analysis is applicable to similar climates, building types, and lifestyles in other regions.

So, it is essential to enhance thermal comfort while maintaining traditional skills. In this context, the government needs to understand how people in different climatic regions achieve thermal comfort in traditional houses by employing various adaptive behaviours, such as using fans, seeking shade, wearing light clothes in summer, and using firewood, drinking hot tea, sitting in sunlight, and wearing heavy clothing in winter. Policies should focus on improving traditional methods with modern skills without compromising cultural norms in order to preserve traditional construction techniques.

(Dr. Gautam is a Ph.D. holder from Tokyo City University, Yokohama Japan.)