- Thursday, 29 January 2026

Democracy Day

Where Does Nepali Democracy Stand?

This year, the government has decided to celebrate ‘national democracy’ day for three days. Yet this is not the first time. Such celebrations, indeed, have been celebrated since 1951, when democracy, which we call modern and liberal, was first introduced in Nepal. Since then, Nepali governments led by political parties of different hues have been celebrating Democracy Day with big fanfare. This author still remembers mishri (a kind of candy) being distributed in the school during the Panchayat period. Interesting as it is, celebrations of this kind certainly depict that there is a certain level of ‘commitment’ towards democracy, at least with regard to ‘celebration’. And over the period of time, those commitments towards celebration alone have also percolated into actions with regard to the democratisation process, which certainly is something of which we can be proud.

There exists a broader sense of "frustration and discontent" in society. While certain aspects are intertwined with the existing political landscape in which democracy operates, others stem from a dearth of opportunities, particularly economic ones, within the nation. In fact, there could be more reasons as well. In that regard, perhaps it will be more appropriate to quote the first sentence of Leo Tolstoy’s novel ‘Anna Karenina', where he says, Happy families are alike, and every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’.

Certainly, Nepalis are no different, and they, too, have more than one reason to be unhappy or frustrated, for that matter, and they are anchored in more than one way.

Today, if we talk to those who are in their early 20s, they feel most unsecured and do not see better prospects in this country, even if they are having a good life out here. The collective insecurity, perceived and real, has become the defining moment of this generation, which has been building up for quite some time. Yet little or no attempts were made to look into their concerns, due to which we have reached a point where every third person is waiting to board the next flight abroad. For all the practical reasons, the mass resignation of people from the state and society raises some key questions about the way we have understood and practiced democracy. Paradoxical as it may be, this is the harsh truth, and if it continues, this may invite what scholars call 'polycrisis', and the permanent nature of such crises would push what is referred to as ‘permacrisis’.

Common phenomenon

This is the type of state we have developed over the last couple of decades. Who do we blame for this? Perhaps this should be our collective failure, and there is a need to accept this fact. Although what we have been observing around the world, dissent with democracy, is not only taking place in Nepal, if it is at all taking place, it is being noticed equally in those countries that claimed to be the most democratic ones. That said, democratic backsliding has become a common phenomenon these days. In that regard, at least two factors could be cited as to why such a state of affairs has arisen.

First, over a period of time, democratic processes (elections and other mechanisms) along with the political sphere have been largely captured by certain classes. For the common people, it has always remained what scholars call a ‘limited or close access order’. Second, the rise of a new political economy (technology included) and technology-induced globalisation per se factors have brought fundamental changes in society. However, politics somehow could not really address those changes in the way they needed to be looked into. In contrast, we could see three diametrically opposite imaginations vis-à-vis the reality of the time with regard to fixing democracy: political imagination, intellectual imagination, and societal imagination.

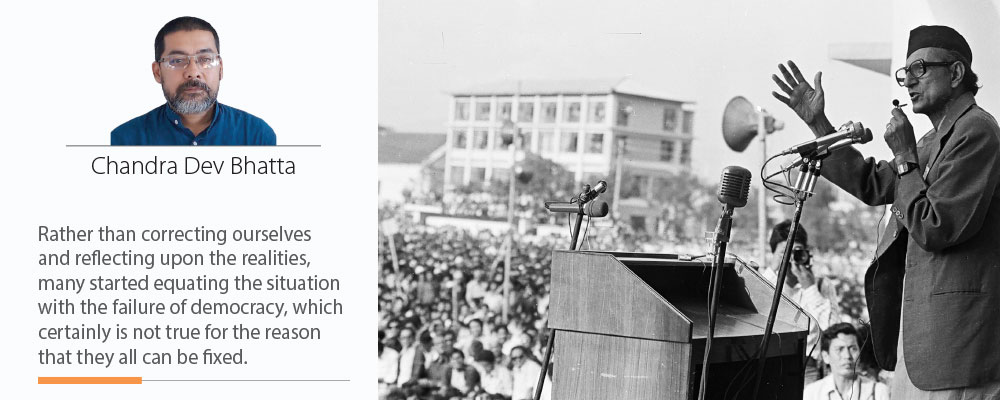

Taken together, they have created a huge gap and led to the rise of populism, conservatism, and nationalism. Such a state of affairs has only pitted what we call ‘progressive’ agendas with ‘regressive’ ones, and vice versa. We have failed to ascertain what is right and what is wrong. On the contrary, a new way of thinking has been developed: what is good for me will also be good for others as well. This certainly is not true, but, sadly, this is the reality that we live in, and democracy has to grapple with it. Rather than correcting ourselves and reflecting upon the realities, many started equating the situation with the failure of democracy, which certainly is not true for the reason that they all can be fixed.

Democracy provides room for improvement and correction compared to many other political ideas and philosophies, but all of these depend on how we acknowledge the problems and communicate with the people. What is certainly true, however, is that democracy is not having the best of times, not only in Nepal but in many other countries where it has been claimed to have roots. Moreover, democracy, in fact, is pitted between far-rightist and extreme-leftist forces, while mediating forces or ideologies in between are becoming weaker for the reasons mentioned above. Also, the return of geopolitics in the form of geo-economics is also bringing its own momentum for all of us and will certainly have consequences for democracy as well, primarily because they are both forcing countries to defend their interests, not their values. Under such a state of affairs, democracy will only become a means but not an end.

Coming back to Nepal, many people are of the view that Byabastha Badliyo, Tara Awastha Badaliyana. For them, there are fundamental gaps between Byabastha and Awastha, and it is this gap that is resulting in a trust deficit towards democratic systems in more than one way. But they are also untrue, partly because, if we go by the fourth Nepal Living Standard Survey (2022-23), Nepal has achieved significant improvement in its livelihood. The level of poverty has come down, though not as expected. Likewise, individual families living standards have gone up in more than one way. The survey clearly indicates that the Awastha of Nepalis has also changed over the decades.

Striking a balance

But what we have missed here is the fact that it has all happened and its social and other costs. The biggest worry for Nepal is that the country has not been able to strike the right balance between political rights and economic opportunities, due to which people at large are dependent on the outside world for their livelihood. It is remittances that have significantly contributed to reducing poverty and improving people’s living standards. But certainly, it cannot be sustainable. Neither would it strengthen democracy in the long run.

We are already bearing the social cost of the current ‘improvement in living standards’ as more than one quarter of the population lives outside for their livelihood. This is where our democracy stands today.

Perhaps the time has come for all of us to realise that we should not simply reduce democracy to a mere occasion of celebration alone, which will, for sure, not yield much for the common people. We need to create a level playing field so that its dividends can be realised by all. Democracy doesn’t need to be defended; what it requires is democrats; that’s what we all have to be.

(Bhatta writes on politics, geopolitics, and other contemporary issues. @Cdbhatta))