- Wednesday, 4 June 2025

Media's Objectifying Beauty Standards

"And if you can’t touch your woman, wherever you want, and if you can’t slap, you can’t kiss, you can’t use cuss words. I don’t see emotions there.” These are the words of Sandeep Reddy Vanga. After Arjun Reddy (2017) and Kabir Singh (2019), two films about chain-smoking doctors with anger issues, the director returns with Animal, about a chain-smoking engineer with deep-seated daddy issues.

“Kabir Singh is an ugly, unforgivable ode to misogyny that reinforces every argument surrounding toxic masculinity, featuring a horrendous, self-sabotaging protagonist who doesn't deserve your pity or your time.” Movie critics had strong negative reactions to the movie's portrayal of toxic masculinity and misogyny. Nonetheless, the audience who loved and enjoyed this movie had their own defence for it, which goes this way: “Come on, it’s just a movie. Don’t take it too seriously.”

It is often said, “A man is the product of the environment.” Mass media is a significant force of communication in modern culture. Everything has a subconscious effect in our mind that might not be realised immediately. Sociologists refer to this as mediated culture, where media reflects and creates the culture. The messages in the media promote not only products but also moods, attitudes, and a sense of what is and is not important. Kabir Singh is a movie that glorifies violence and abuse. Many people started idolising Kabir Singh to the extent that a tiktoker ended up killing an air hostess because she was marrying someone else, resonating with the movie’s dialogue saying that "jo mera nahi hosakta usse mein kisi aur kaa hone nahi dunga." This translates to, "What cannot be mine, I won't let that be anyone else’s.

Making films is a power, and with power comes responsibility. But directors such as Vanga do not care about the impact that their kind of movies leave on society. They only have one mantra, and that is that violence sells. In the movie Animal, despite the fact that the protagonist is portrayed as the father of a daughter, he mocks the discomfort of menstruation. He tells his wife that it’s a man’s world. He tells his lover to lick his hand to prove that she loves him. And all of these actions are justified or even glorified. As Aamir Khan had said, "Directors who are not very talented creatively, in creating a story and showing emotions, depend heavily on violence and sex to make their films work.”

Along with movies, music videos have also long served as a powerful medium for storytelling and artistic expression. These audiovisual creations, accompanied by catchy tunes, captivate audiences worldwide. Yet, beneath the surface of entertainment lies a troubling undercurrent: the persistent objectification of women within the imagery and narratives. From provocative costumes to suggestive choreography and lyrics laden with innuendo, these portrayals contribute to a culture that has been scrutinised for perpetuating harmful stereotypes and shaping distorted perceptions of femininity.

In every Bollywood song, one item is necessary to attract a larger male audience in the theatres and satisfy their male gaze. The lyrics belittle the women and identify them as mere objects. In the song “Fevicol se,” women are compared with Tandoori Murgi, who says that men can gulp alcohol. There’s another song called “aa ante amalapuram," in which the puberty of a girl is depicted in such a way: "Umar mero athara hone chali (My age is going to be eighteen), Hata de chhilka u mere dil kaa (Remove the cover of my heart), aa kha le moong phali (Come and eat the peanuts). In this song, subliminally, the girl’s virginity is being compared to a peanut shell. Madhuri Dixit had gracefully pulled off the dance in a song, but surely that doesn’t change the meaning of the words, which say, “choli k piche kya hai, chunri ke niche kya hai." This translates to, “What’s behind the blouse? What’s under the scarf?" "Kaddu katega toh sab pe batega” is something that exceeded its limits. It translates to “Once there is defloration, everyone will get a share.” This song actually normalises gang rape and is still enjoyed like nothing.

Nepali songs are no better. When “Ghati bhanda tala ta ramri nai chey" by Arjan Pandey was released in July 2019, the comment section exploded because of the chorus that translates, "She is at least beautiful from the neck down." The lyrics totally describe men’s lust for women’s bodies, yet people have been enjoying the song over the years. Another such song is “Timi aauchau ki arkai bihe garau,” which fuels the stereotype. If a woman stays in her paternal home for a bit longer, then the husband threatens her that he’ll marry someone else. "Saali Manparyo’’ is another popular song that presents the chemistry between a brother-in-law and a sister-in-law. The strange part is that the song with such offensive lyrics is played mostly at wedding ceremonies.

All these songs are easily accessible to all age groups. These songs use metaphors to objectify and sexualize women, which in turn normalises sexual abuse in real life.

“I feel like I've been conditioned to believe that in order to be taken seriously, I need to appear and dress better. My confidence changes when I wear makeup, especially when it comes to dating. Because it is in our tendency to seek beauty." Prashna Bhattarai, a corporate worker, says, "It is disheartening that these unrealistic and objectified versions of beauty shape the perception of 'pretty'."

"This is a cycle; objectification sells, so there's very little motivation to actually change how women are portrayed in their work," she continues. Furthermore, exposure to harmful portrayals, particularly among younger members of the population, lays the groundwork for a liking for similar content. The 'popular' stream provides stuff that sparks disagreement, which we enjoy.

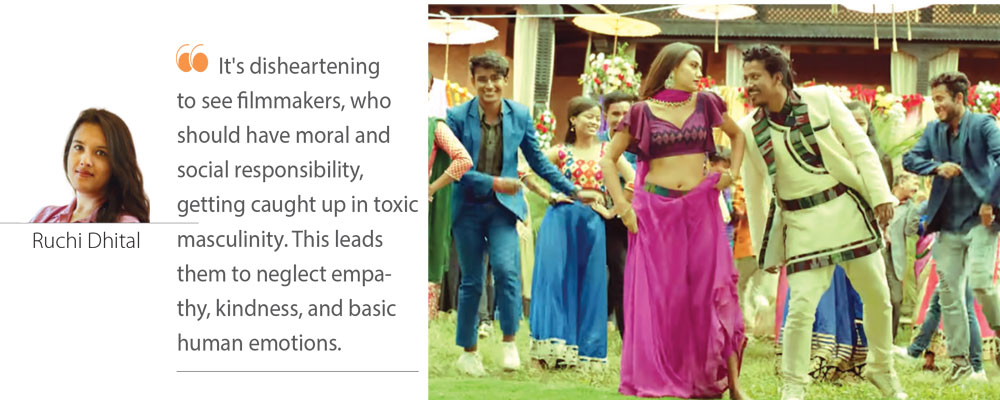

It's disheartening to see filmmakers, who should have moral and social responsibility, getting caught up in toxic masculinity. This leads them to neglect empathy, kindness, and basic human emotions.

(The author is a law student at Kathmandu School of Law.)

-square-thumb.jpg)