- Sunday, 18 January 2026

Make Teachers More Accountable

At a policy dialogue held the other day under joint auspices of National Teacher Service Commission and Policy Research Institute (PRI), senior university officials, educationists and experts attributed several reasons to cause a deterioration of standard of school education in Nepal. Some argued that the poor investment in education sector is the reason why school education has failed to deliver. They stated that over twenty per cent of the total national budget should be allocated for quality school infrastructure development. Others insisted that school supervision system needs to be strengthened to ensure that teacher’s delivery especially in classroom was appropriate and effective. Some educationists contended that teaching profession has not been attractive enough because of poor financial and moral rewards and incentives offered to them.

Teachers have not been given due respect and recognition in the community whereas government employees of the same ranks command more respect, rewards and appreciation in the society. This has made teaching occupation less attractive and less rewarding. As a result, qualified and educationally competent candidates do not prefer to join teaching as an enduring and settled profession. There are opinions that accuse government of exercising reluctance to devolve sufficient authority to the local level in regard to education service delivery and endow the local governments with capacity to undertake the responsibility. Though the federal constitution entrusts mandates and competencies for administration and management of schools to local governments, this has not been realised in the real sense of the term.

Lack of incentives

The central ministry does retain its hold through one’s own agency over the management and administration of the schools at the local level. In fact, the National Teacher Service Commission that is legally mandated to oversee and conduct examination for the selection and recruitment of teachers has not been able to receive required number of qualified applicants for different category of disciplines such as mathematics and science. Two reasons, according to the experts, can be cited in this respect. Either there is insufficiency of qualified candidates or not much attraction or incentive exists to attract them to join teaching as an occupation among the qualified candidates.

Moreover, there are several instances to show the way as to how government acts for political expediency in defiance of the values and standards of quality school education. The government had agreed not very long back with the association of the ad hoc teachers committing that they would made the regular and permanent without having to go through standard open and fairly competitive test. Such and many other short-sighted decisions of the government capitulating to the pressures and influence of the vested interests have created adverse consequences to impair the education system in the country.

The government had also proposed to provide incentives to the teachers and government employees who choose to send their children to study in the government-aided community schools. However, it did not help much. Today it is found that teachers in the community schools, irrespective of the levels, send their children in the private schools indicating that they themselves have no confidence in the teaching learning environment in the schools that they are venerated, paid for and employed in the privileged and respectable position of teachers and educators. When the teachers who need to own and be accountable to the teaching and learning outcomes in the school have lost their trust in the learning effectiveness in the schools they are associated with, it is almost futile to expect the improved and the quality learning environment in the public schools.

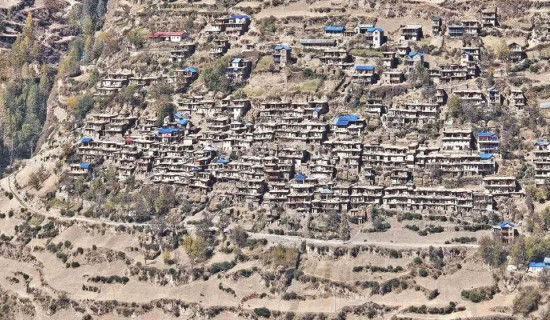

In Nepal, during early seventies, the government made a national policy making education a subject of national government obligation. Though the reach and expansion of the schools was limited and confined to some convenient locations in the district in those days, education imparted to children in the public schools was uniform where students from haves and have-nots communities attended and received education. It means that same level and quality of education was imparted to the children no matter differences and disparity in their social and economic status and background.

Public school education was a kind of equalizing and levelling means as children of rich and poor, upper and lower caste groups joined in the same school and shared the same educational pedestal and facilities. When the education sector was liberalised and opened for private sector participation especially during late eighties through amendment to the Education Act and Rules, it unleashed an unregulated mushrooming growth of the private schools both in the urban, semi-urban and even in the rural areas of the country. The private schools slowly captured the education landscape. As a consequence, the social and political elites started to disown and discard public school education on various counts.

Lucrative business

First elites and well off communities let down and withdrew from the public schools leaving them to fend off for themselves by sending their children to the private schools. Moreover, as private schools and colleges became more of a kind of lucrative business enterprises and ventures, political and social elites emerged as the key and important stakeholders for private investment in education sector. Today they can foil any policy initiatives and measures to rein in and regulate the private schools.

Once elites and educated group of people lose their stakes and interest in the quality of public school education, the social support, participation and pressure to ensure and maintain the quality of education in public schools is bound to be insufficient. The crux of the matter lies as to how to strengthen and expand public stakes and ownership for education as it is the core and obligatory function of the state in a democratic society.

(The author is presently associated with Policy Research Institute (PRI) as a senior research fellow. rijalmukti@gmail.com)

-original-thumb.jpg)