- Tuesday, 3 March 2026

A Journey To Taj Mahal: My Dream Comes True

I visited New Delhi recently accompanied by my family members with two purposes: health checkup and cultural tourism. We visited Kurukshetra which is famously known as the battlefield of the Mahabharata war.It is here that Lord Krishna delivered the Bhagavad Gita to Arjuna — a foundational text of Hindu philosophy and ethics. Our visit to Kurukshetra was spiritually enriching enough but this piece refers to and takes cognizance of our visit to Tajmahal in the historic city Agra.I had known about Tajmahal as one of the seven wonders in the world from a moth-eaten general knowledge book when I was a school boy. My brother Mohan Rijal used to read aloud about it and I had picked and could recite the names of seven wonders in the world at one go even before I could simply read and write.

But later almost two decades ago, when I was working as the news desk editor in the Rising Nepal English daily my attention was caught by the AP transmitted news regarding the then US president Bill Clinton’s visit to Tajmahal. According to media reports among modern high level visitors, perhaps none expressed the awe and admiration toward the Taj better than U.S. President Bill Clinton, who visited the marble dome along with his daughter Chelsea and the Secretary of State Madeleine in Clinton administration. Once inside Tajmahal ,Clinton was overcome by wonder and wrote in the visitor’s log book “I’ve wanted to come here my entire life,”. According to reports, Clinton spent nearly ninety minutes touring the site, carefully observing the inlays and symmetry of the marble dome. Moved by the monument’s grace , perfection and also its fragility engendered due to pollution cause due among others oil refineries , he remarked:“Atmospheric aollution has managed to do what 350 years of wars, invasions and natural disasters have failed to do — it has begun to taint and corrode the magnificent walls of the Taj Mahal.”

For Bill Clinton, according to the Indian media , the Taj became a symbol not only of love but lately of the ecological necessity requiring urgent need to protect this planet’s wonder. He used the backdrop of his visit to Tajmahal to speak about clean energy and environmental cooperation between India and the United States linking the preservation of monuments with the conservation of nature itself.

When touring around New Delhi I had shared my interest to include Tajmahal in our itinerary , Dhiraj Khanal of the Manakamana Guest House at Gurugram where our family members were staying made a plan and accordingly took us to Agra in his car own car to see Tajmahal on our way back home in Nepal. It was, indeed, a journey I had long pined for. I had a deep interest to catch a view of Tajmahal from upclose - the marble wonder that has impressed poets and amazed emperors, and travelers for centuries. Setting out from Gurugram Delhi, our car took the Yamuna Expressway, the gleaming modern road that connects India’s capital Delhi to historic city of Agra — a 165-kilometer stretch of smooth highway. In fact, the expressway runs almost like a silver ribbon through the rural heartland of Uttar Pradesh including Jewar , Mathura, Hathras and so on. According to the report ,the Yamuna Expressway project was “conceived” by the Uttar Pradesh government in 2001. A special authority — originally called the Taj Expressway Authority (TEA) was created by the UP government to oversee the project. The agreement for the construction of the expressway was signed between UP government and Jaiprakash Industries Ltd which would build and operate the expressway. This Kind of PPP model could be effective in the case of Nepal as well especially for road infrastructures.In fact we need to emulate it.

However, the project was delayed and took a long time from conception to completion, according to media reports. The construction was completed around May 2012. The development minded young chief minister of UP Akhilesh Yadav- who had claimed credit for the project and used it for electioneering purpose - inaugurated it in 2012. What once was a five-hour trudge through congested towns on the historic old Grand Trunk Road (GTR) is now a serene two-hour drive through open plains and farmland.

On the way to Tajmahal from Gurugram , I saw the landscape unfolding like a celluloid sequence — fields of mustard, roadside dhabas (eateries) punctuated by toll plazas. Our journey itself had symbolic significance : from the modern India of expressways and technology to the timeless India of marble domes and stone sculpture. As we approached Agra, the city of the Mughals unfolded before us with red sandstone walls and din and bustle of local bazaars.

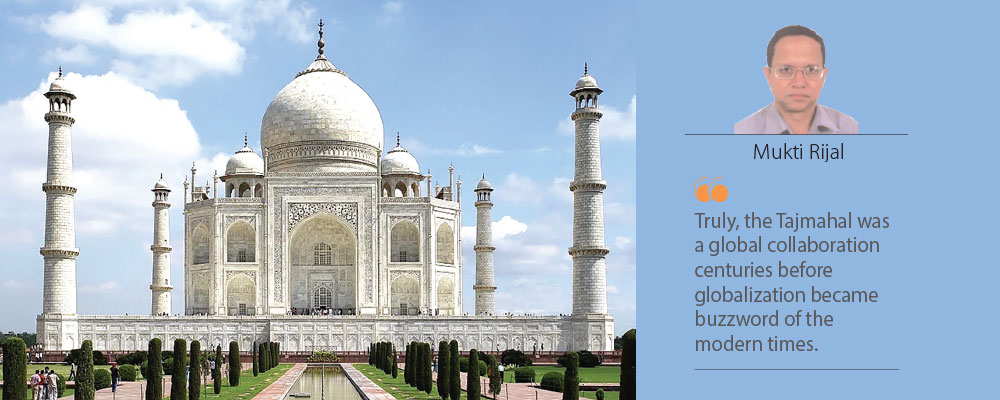

According to an article published in the Frontline – newsmagazine published from Chennai , Taj mahal was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal, who had died due to childbirth complications in 1631. Tajmahal’s construction began in 1632 and continued for more than a decade, with contributions from artisans and architects from across India, Persia, and Central Asia.

Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, of Persian descent, is believed to have been the chief architect. Under the supervision of Makramat Khan and Muhammad Isa Afridi of Turkey, the mausoleum took shape as a perfect blend of Persian, Turkish, and Indian aesthetics. The inscriptions were executed by Amanat Khan of Shiraz, the inlay work by Hindu artisans from Kannauj, and the dome was raised by Ismail Khan, also of Turkish origin. Truly, the Tajmahal was a global collaboration centuries before globalization became buzzword of the modern times. Taj mahal’s story is steeped in legend and emotion. Shah Jahan, according to historical reports , was inconsolable at the death of Mumtaz Mahal. His grief turned into creation, his sorrow into splendor. The tomb became a physical manifestation of love and also of impermanence, as Rabindranath Tagore – the first Nobel Laureate in literature from Asia so beautifully captured when he called Tajmahal “a teardrop on the cheek of time.”

Those lines echoed in my mind as I gazed at the dome. It seemed less like stone and more like emotion embodied in it. The Tajmahal was not just a monument of love but also a philosophy carved in marble - that beauty can arise from sorrow, and art can triumph over mortality. Over the centuries, countless travelers — from Mughal chroniclers to modern tourists have written about their visit to the Tajmahal. Bishan Chand, a court chronicler, described it as “the wonder of Shah Jahan’s reign”, while British high level officials like Lord Curzon saw it as “the most beautiful building raised by human hands.” Lord Curzon, very dynamic and strategist governor general of the British Raj in India who undertook major restoration efforts during his viceroyalty, said after visiting Tajmahal : “If I had never done anything else in India, I have written my name here, and the letters are a living joy.”

Modern historians such as Ramesh Chandra Majumdar and Perceival Spear interpret the Taj as the culmination of Mughal architecture, the perfection of experiments begun with Humayun’s Tomb and Fatehpur Sikri. They call it “a symphony in stone,” where floral inlay, garden geometry, and marble carving reach their ultimate harmony. No Indian leader articulated the Taj’s aura better than Jawaharlal Nehru, who wrote of it as “a dream in marble” — a vision of harmony between art and emotion. In his magnum opus “The Discovery of India”, he placed it among the supreme creations of human imagination, symbolizing not just love but also the synthesis of India’s diverse cultural streams. For Nehru, the Taj was an evidence to adduce that art could transcend politics and religion, merging Persian grace, Turkish symmetry, and Indian craftsmanship into one immortal grand structure.

At a 1959 seminar on architecture organized at Bigyan Bhawan Newdelhi , Nehru had given inaugural address and reflected:“The Taj Mahal is, of course, one of the most beautiful things anywhere, and it is a delight to the eye and to the spirit to see it. It represented, as all architecture represents, the age in which it grew — you cannot isolate architecture from the ideals of that age.”For him, according to the proceedings report, the Taj was not a relic of a bygone empire but a living part of India’s artistic consciousness.

Poets like Sarojini Naidu who was one of the best known fighter for India’s independence called it a “white marble dream,” describing how it changed colors with the movement of the sun — pink at dawn, white at noon, and silver under the moonlight. She saw it as alive, breathing with the rhythm of time.

In recent years especially after Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP ) came to power, the Taj Mahal has been subjected to political and cultural debates. Some voices have questioned its origins, falsely claiming that it stood on the site of a temple. Yet, amid these controversies, leaders such as Yogi Adityanath- incumbent Chief minister of Uttar Pradesh have reaffirmed that the Taj remains a “gem built by the sweat and blood of Indian laborers,” and that its preservation is a national duty. Indeed, beyond politics, the Taj stands as a symbol of collaboration — a monument born of many faiths, many lands, and many hands.

Despite pollution and urban sprawl, the Taj continues to attract millions of tourists from different parts of the world every year. According to a booklet this writer collected from the souvenir shop in Agra In the fiscal year 2023–24, it earned nearly 98.5 crore in ticket revenue alone, a testament to its enduring attraction as a tourist venue.

Travelers through the centuries — from Persian chroniclers to modern presidents have felt compelled to write about Tajmahal because I feel Taj Mahal is not just seen; it is experienced. It overwhelms and humbles, reminding one of both human transience and the enduring power of art.Centuries have passed since Shah Jahan’s time, empires have fallen, and cities have transformed. Yet the Taj mahal remains invincible against time. It is at once personal and universal, intimate and monumental. The Taj Mahal, that teardrop on the cheek of time, had fulfilled my dream but more than that, it had taught me what all great journeys teach. The moral is:beauty of the monument is not just to be seen, but to be felt; not merely admired, but remembered.

(The author is presently associated with Policy Research Institute (PRI) as a senior research fellow. rijalmukti@gmail.com)

-original-thumb.jpg)