- Wednesday, 25 February 2026

Everyday Life Amid Social Media Crisis

Nepal is going through a very tough time right now. After the Gen Z movement exposed how badly the old political parties had failed, we have elections scheduled for March 5, 2026. But those same parties don't want to face voters anymore because people have seen their decades of failure. So they're resorting to social media manipulation like never before.

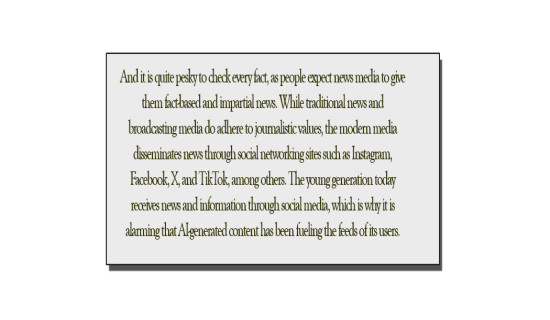

The worst part is how they're using AI now. The CPN-UML reportedly distributed petrol and food coupons to their cadres for rallies, and when caught, they claimed the photos were AI-generated. When reports came out about money found at Sher Bahadur Deuba's house, he dismissed it as AI-created. Now the public faces a paradoxical situation: how do you know what's real when anyone can say "that's AI" whenever something inconvenient surfaces? This shows why Nepal's social media problem is far more dangerous than what Western countries face.

Social media manipulation

Western countries definitely have fake news problems. Trump's use of "alternative facts" in his first presidential term, political polarization creating separate realities for different groups, Russian and Chinese interference during elections, QAnon conspiracies, anti-vaccine movements testify to this. Even Western rationalist traditions can't really protect against misinformation. But here's the key difference. In Western countries, even during election chaos, the manipulation stays mostly at the political level. People argue about which news channel or politician to trust. But their everyday life remains protected by functioning institutions. Doctors are licensed, charities are verified by authorities, schools meet accreditation standards. These institutions aren't perfect, but they work at a basic level.

In Nepal, manipulation has penetrated every aspect of daily life. In healthcare, can you really tell if a doctor is qualified? Professional licensing exists on paper, but enforcement became very weak after we restored democracy and declared the republic. Why? Because major political parties cared more about keeping their partymen happy than about professional standards. Unqualified people affiliated with parties got to practice medicine with almost no oversight. Same thing in education. Unqualified teachers got positions through political connections, not merit.

The charity sector often suffers from a lack of accountability, and the case of Dhurmus and Suntali is a prime example. The beloved comedians first earned public trust through genuine humanitarian work, aiding Nepal's earthquake victims and the impoverished Musahar community. They were rightly celebrated, and their social media influence channeled real donations. Success seemingly led them astray, though. They pivoted to an ill-conceived plan to build a cricket stadium, claiming they'd contribute to the sport sector since the government had been ineffective at such projects. The stadium would help reduce unemployment and provide other social benefits, they argued, using emotional appeals spread through social media to maintain support. This shift, funded by small public contributions, revealed a troubling desire to monetise their popularity, moving from humanitarian work to what many perceived as greed.

Lack of a charity watchdog

Many organizations now have impressive Facebook pages asking for donations with emotional appeals, but how do you verify which are genuine and which are fake? There's no charity watchdog with real authority. This institutional weakness isn't accidental. It's the result of decades of party politics that corrupted everything. National projects became vehicles for party patronage instead of public service. This is exactly why the Gen Z movement took place. Young people saw this for years and got fed up. But now those same parties use social media manipulation to avoid accountability and try to stop the March 2026 elections. All major parties operate "cyber armies" that constantly generate propaganda and attack critics. This isn't just during elections, it's 24/7. Professional journalism still exists but gets drowned out by social media content creators with no standards or accountability.

Different cultures think about truth and knowledge differently. Western culture emphasises skepticism and evidence. South Asian culture, including ours in Nepal, integrates different ways of knowing. We value rational analysis but also emotional intelligence, empirical facts but also spiritual understanding, individual judgment but also community wisdom. These are real strengths, not weaknesses. But here's the catch about our political culture. In Nepal, people are hardly judged based on actual skills or performance. We like or dislike people based on whether they're from our political party, share our ethnic identity, and fit into our social hierarchies. Actual competence and governance outcomes are often secondary.

A powerful manipulation tactic exploits our cultural respect for family. Political figures get positioned not as the leaders they actually are, but as emotional archetypes. KP Sharma Oli becomes "Baa," father. Deuba becomes "Daju," brother. Arju Rana Deuba becomes "Bhauju," sister-in-law. Sushila Karki was first called the nation's "loving mother." The danger is people don't evaluate these individuals based on their performance as prime ministers or ministers. They respond to the emotional archetype. When someone is "father," people think of wisdom, protection, authority, and respect. Criticising them feels like betraying family. This creates a dangerous generalisation: father figures and mother figures can't make mistakes, we shouldn't scrutinise their actions, and we should forgive their failures.

Both Nepal and Western nations face manipulation, but the danger differs fundamentally. In the West, manipulation targets political opinions during election cycles. In Nepal, manipulation is constant and affects survival decisions in healthcare, charity, education, and finance. In the West, institutions protect everyday life even in case of political interference. In Nepal, decades of party-fed corruption have eliminated this baseline protection. When foreign actors influence Western elections, citizens might elect bad leaders, but their teachers are still certified, medications still regulated, and charities still verified. In Nepal, people can't trust political information, medical credentials, charity legitimacy, educational qualifications, all simultaneously, all the time.

We need digital literacy adapted to our culture, using Buddhist and Hindu concepts as a foundation, teaching people to recognize manipulation in healthcare, charity, education, and finance. We need to strengthen investigative journalism to expose cyber armies and reveal hidden motivations. We need transparency requirements beyond politics for anyone soliciting donations or claiming expertise. We need public awareness about specific tactics: the "AI defense," cyber army coordination, performative altruism fraud, vigilante journalism as extortion.

Call for action

When I was an English literature student, I read John Milton's "Areopagitica" from 1644. In it, Milton argued that truth emerges through free encounter with falsehood, not censorship. Maybe Nepal's chaos is something we must go through, like Western societies experienced before developing solutions. But critical differences demand urgency. Viral content spreads instantly, not slowly like Milton's pamphlets. We must develop journalism ethics and frameworks while confronting algorithmic manipulation, cyber armies, and AI fabrication. The current political crisis shows how fast things deteriorate. The costs of delay are measured in destroyed livelihoods, damaged health, and daily suffering.

Nepal does have resources: philosophical traditions offering truth frameworks, cultural strengths in solidarity, and proven adaptive resilience. The challenge is developing the capacity to maintain these strengths while resisting exploitation. We need conscious action now in education, media support, transparency, and public awareness. This will determine whether technology serves our growth or enables exploitation. As Milton understood, this struggle is necessary for genuine understanding and cultural strength. The question, however, is whether we'll act with sufficient speed before costs become unbearable.

(The author is an Associate Professor at the Department of Writing, Rhetoric and Composition at Syracuse University, New York.)