- Thursday, 15 January 2026

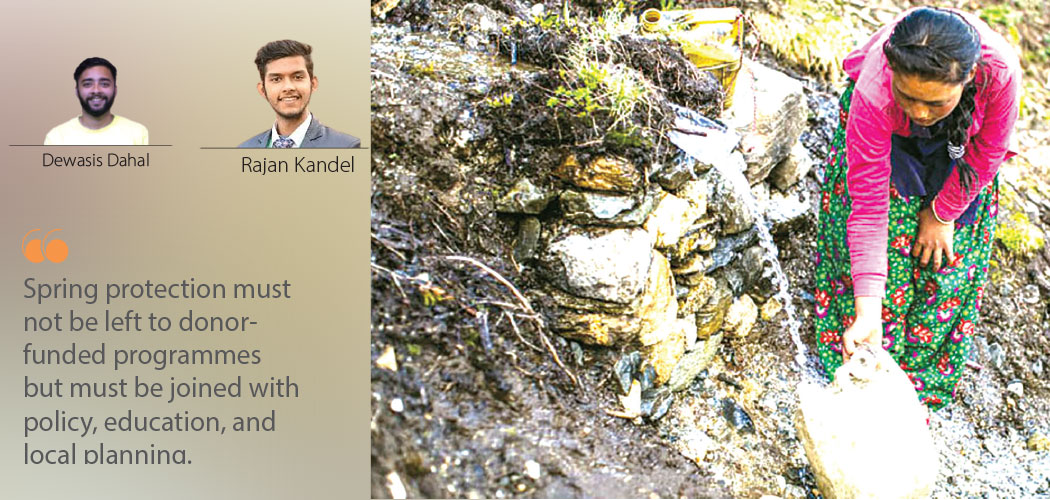

Highland Natural Springs Disappearing

What would you do if the only spring in your village dried up, leaving you to walk three hours daily to fetch water, and even worse, forcing you to leave behind your home, land, and memories in search of survival?

This isn't hypothetical for many communities living in Nepal's highlands – it's their everyday reality. Kamala Tamang used to walk just 20 minutes to collect water in Bidur Municipality back in 2018. Now, it takes her nearly two hours. She's not alone – many people in her community spend much of their day just trying to get enough water to live.

Communities across Nepal's highlands are facing an increasingly severe crisis: the disappearance of natural springs. These springs are more than just water sources; they are the lifeblood of agriculture, culture, and livelihoods. This deterioration of the environment threatens something more than water access: it risks displacing populations, disrupting agriculture, and reshaping entire ecosystems.

Causes and overlooked risks

Recent studies reveal a troubling national trend: natural springs in Nepal's hills and mountains are drying up at an accelerating pace. Over 300 local governments' data indicate that 74 per cent have drying springs, 44 per cent are experiencing significant impacts on drinking water sources, resulting in migration in 7 per cent of local governments.

The problem is most severe in the Chure region, followed closely by the mid-hills and the mountain belts. Dapcha and Tinpiple of Kavre District have witnessed 29 per cent and 14 per cent of their springs vanish, respectively. ICIMOD reported that 93 of 444 springs in Namobuddha Municipality dried, with many others experiencing reduced discharge. The western mountain watersheds paint an equally grim picture. About 70 per cent of springs flow at reduced levels in the study of the five watersheds. In the Karnali River Basin alone, of 6,646 spring sources identified by a study, 3 per cent were severely degraded, nearly 80 per cent were moderately affected, while only 17 per cent were healthy.

A complex interaction of natural and human causes brings about the reduction in spring flow. The most significant reasons for the drying up of springs are altered water uses, increasing population, unsustainable development practices, natural disasters, and climate change. Deforestation and intensified land-use changes, mainly in urbanising regions, have stripped the hills of vegetation cover, leading to dry soil and less groundwater recharge. Construction of infrastructure, particularly roads along slopes, has disrupted natural recharge zones and groundwater flow. Additionally, frequent wildfires cause soil hardening and kill organisms, resulting in soil moisture loss and diminishing the water-holding capacity.

Climate change further amplifies these stressors. Irregular rainfall patterns, shrinking glaciers, and reduced snowmelt have weakened groundwater replenishment. The increase in extreme precipitation events increases the surface runoff. The higher altitude region is geologically fragile and cannot withstand higher rainfalls, which trigger landslides. These combined forces diminish the spring discharge, undermining water access for thousands living in higher altitudes.

Despite the growing crisis, national water, land use, forestry, and climate change policies have largely overlooked the importance of spring and springshed management. Researchers have pointed out critical gaps in policy frameworks, mainly the absence of dedicated mechanisms for managing springsheds. Traditional watershed management approaches focused on large-scale ridge-to-valley dynamics fail to address the unique needs of springshed conservation. The spring source protection and conservation guided by the springshed management approach in water resources are strongly required in the policies. The government's emphasis on glacier retreat and high-altitude lakes is seen increasing; however, the urgent crisis of drying soil and springs in the mid-hills is being neglected.

Spring's revival challenges

Despite the challenges, several encouraging interventions have emerged. Several local governments in Nepal have demonstrated proactive efforts in spring source management. One of them, the Sarvodaya Municipality in Ilam, has declared certain areas as "dry zones" and introduced a "One Ward–One Pond" programme to address spring drying, along with enforcement of regulations that prohibit deforestation and the use of pesticides within 50 metres of spring sources. In the far-western district of Dadeldhura, WWF Nepal collaborated closely with local communities to construct 22 recharge ponds, utilising traditional knowledge of rainwater harvesting practices. In the fragile Chure hills, CDAFN implemented watershed restoration by building 180 rainwater ponds across the upper catchments of several rivers, including the Ratu and Maraha.

ICIMOD led significant work in developing and implementing the springshed restoration methodology in the Dailekh and Sindupalchowk districts. The success in both areas proved that such scientific methods could be applied broadly across diverse social and geographic contexts. ADB focused on strengthening the climate resilience of watersheds in mountain eco-regions of Nepal from 2011 to 2021. The outcomes included improved food security, sediment control, wetland conservation, and significant gains in groundwater recharge.

The loss of springs is an ecological issue and drives social instability. Water insecurity has contributed to internal migration, as people abandon dry settlements in search of reliable water sources. Even modern rainwater harvesting systems that collect and filter rooftop runoff fail during prolonged dry seasons.In multiple hilly regions, wildfires have directly disrupted piped water supply systems. The combined impact of infrastructure damage and environmental degradation makes it harder for spring source-dependent communities to survive. Communities are increasingly practising alternative cropping, such as cultivating drought-tolerant crops, such as millet and okra, due to increased vulnerability of the water sources.

There is no question that Nepal's water systems are undergoing a dramatic transformation. Studies suggest that spring sources are shrinking and drying out rapidly. The elevated regions face more severe problems more quickly than in slightly lower areas. The springshed management policies and activities are urgently required for spring source conservation and rejuvenation. Nepal must shift from reactive, fragmented efforts to coordinated national strategies. Spring protection must not be left to donor-funded programmes but must be joined with policy, education, and local planning. Tools of science and community knowledge are the means to build resilience in the hills. Solutions must be localised in spring revival interventions, complementing Nepal's diverse geologies and precipitation regimes.

As springs dry up, the tradition, practice, and culture of people who have depended on them for generations also disintegrate. It is not only an ecological issue to restore these valuable water sources. It is a social, economic, and cultural necessity for Nepal's future.

(Dahal is a water resources engineer at Maurer-Stutz, and Kandel is a research assistant at Kathmandu University.)