- Saturday, 14 February 2026

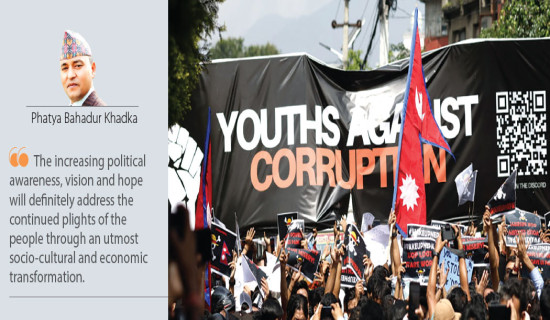

Collective Action Checks Corruption

Corruption has been a persistent issue in Nepal for decades. However, the latest corruption cases highlight a serious governance challenge. Two recent major cases have once again brought it to the attention of the general public and the federal parliament in particular, igniting discussion from tea stalls to parliament. The first case involves alleged visit visa-related malfeasance under the Immigration Department of the Home Ministry. While opposition parties, particularly the Rastriya Swatantra Party, are obstructing and protesting in the House consistently, demanding that Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak resign from his post and a high-level parliamentary investigation committee or an independent judicial probe committee be formed to look into this scam.

The second scandal pertains to the Patanjali Yogpeeth-related land case. In this connection, the CIAA filed a case against former prime minister Madav Kumar Nepal and other government employees at the Special Court, accusing him of making a policy decision that enabled the illegal sale and exchange of land exceeding the legal ceiling acquired by Patanjali Yogpeeth. This suggests that corruption is no longer just personal misconduct but it is also a systemic problem, requiring structural reforms and public accountability for the restoration of public trust and democratic integrity in Nepal.

Historical roots

Corruption is not a new phenomenon. For instance, two thousand years ago, Chanakya, in his book Arthashastra, mentioned it. Thirteen centuries ago, Dante, in his 'Divine Comedy' placed bribe-takers in the deepest parts of hell, reflecting the medieval corrupt behaviour. William Shakespeare has described corruption in his plays and the American Constitution made bribery and treason two explicitly mentioned crimes that could justify the impeachment of a U.S. president. Corruption, therefore, has been a persistent governance challenge across ages and cultures all over the world.

Today, the global community recognises corruption as a major barrier to development and human rights. To deal with it, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), 2003 was adopted. And Nepal is a signatory to this convention and has implemented the Prevention of Corruption Act, 2002, as its domestic enforcement law. Moreover, Nepal is party to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC), 2000, which is enforced through the Organised Crime Control Act, 2013. These instruments give Nepal both the mandate and legal tools to combat corruption.

The understanding of corruption has significantly widened over the years. Traditionally, it is defined as “abuse of public office for private gain," but Transparency International defines it more inclusive way. It states that corruption is "abuse of trusted authority for private gain," acknowledging that corruption takes place in both public and private spheres.

It operates through various mechanisms. It ranges from bureaucratic (petty), such as small bribes for services, to political (grand), such as high-level embezzlement. It can be cost-reducing or benefit-enhancing, coercive or collusive, and centralised or decentralised. Payments can be made in cash or non-cash mode, such as jobs or political favours. Most importantly, sometimes the bribe is demanded, and other times it is offered voluntarily. These variations show that corruption is complex, suggesting policymakers design targeted interventions rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

It is equally important to note here that economist Robert Klitgaard's famous corruption equation - corruption = monopoly + discretion – accountability - provides a diagnostic tool for institutional vulnerability assessment to understand corruption. This means corruption is more likely when officials have exclusive control (monopoly), make decisions without clear rules (discretion), and face little oversight (accountability). This idea helps us to see corruption not only as personal failure but also as a failure of systems and structures.

For example, in Egypt, systemic corruption was so entrenched that it earned the nickname Fasadestan (land of corruption). Scholar Lisa Blaydes found that it became a tool for control, not just enrichment. Likewise, in Malawi, the cashgate scandal exposed how fraud in the public payroll system weakened government services and scared off foreign aid. These cases show how corruption, if unchecked, becomes part of the system itself. Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) shows that Nepal scored 34 out of 100, one point drop from the previous year. This places Nepal at 107th position among 180 countries, indicating deepening challenges in public sector integrity.

Corruption is difficult to detect. Unlike other criminal offences, it rarely leaves clear victims. According to research, for corruption to be addressed, someone must witness it, recognise it as a form of corruption, feel safe to report it, and have access to an effective institution that can take action. Corruption prevention is therefore not only about rules, but also about promoting ethical behaviour, protecting whistleblowers, and ensuring fair treatment. Additionally, it is about understanding the social characteristics that influence corruption talk: gender, age, religion, ethnicity, and so on may all play a role, as will differential engagement with international anti-corruption discourses themselves.

Investigation

An investigation is needed to uncover wrongdoings and punish offenders. Prevention involves redesigning systems to remove opportunities for corruption. Education ensures people understand why corruption is harmful and how they can be part of the solution. Together, these approaches reinforce each other.

In conclusion, the pattern of corruption seems to be transforming from isolated petty incidents to more systemic. This shift raises a pressing concern: Is Nepal, too, on the verge of becoming what Egypt was once labeled as 'Fasadestan'? Combating corruption requires more than reactive legal actions grounded in ethics and public accountability. It demands a collective and shared commitment from government bodies, civil society, media, law enforcement agencies and stakeholders to reinforce a zero tolerance culture.

(The author is an advocate.)