- Saturday, 21 February 2026

Indian Views On Nepal-India Ties

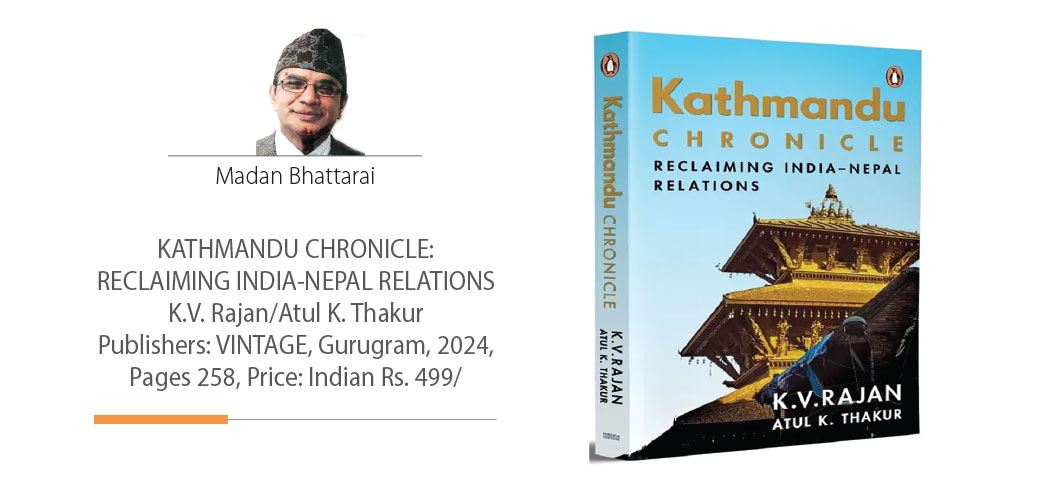

It is perhaps difficult for a career diplomat trained to send confidential dispatches to write a book dealing with one's professional discipline. The exercise becomes more complex regarding major diplomatic assignments involving close and multi-dimensional, yet complicated, strands of Nepal-India relations. An officer of the 1965 batch of the Indian Foreign Service, Krishna V. Rajan, has attempted a new book, Kathmandu Chronicle: Reclaiming India-Nepal Relations.

Ambassador Rajan's first book was an anthology of essays contributed by 16 ambassadors, including himself, entitled The Ambassador's Club: The Indian Diplomat At Large, which he edited exemplarily, which was decidedly an easy task. However, this particular work, though undertaken in joint authorship with a policy professional and familiar, Atul K. Thakur, necessitates a stamp of his feedback and opinion.

In the annals of Nepal-India ties, there have been incessant complaintss of high-handedness and erratic behaviours, with a constant feeling that both have failed to navigate such a seemingly close relationship for mutual advantage and hassle-free linkage. Both profess sovereign equality and non-interference, commitments to the spirit of the Non-Aligned Movement, and principles of Panchsheel and peaceful co-existence.

There is, however, a feeling in Nepal that Indian diplomats, media, and intellectuals either take for granted or harbour a habitual bias against Nepal and the Nepali regime of all hues, with a dose of prescriptions and even proscriptions as if Nepal is unable to steer foreign policy in its interest. It is against such a status that the new book possibly proves what a famous American writer and film director, Carey Williams, defines as a diplomat's requisite qualification of "speaking several languages, including doubletalk".

On the most personal aspect, Ambassador Rajan is a popular figure visiting Nepal with his charismatic wife, Gita Rajan, occasionally, even after leaving office in Nepal and retiring from service as secretary soon after. As the 16th appointee, he has the distinction of serving Nepal for the longest period (five years and three months) among 26 ambassadors, surpassing Bhagwan Sahay's stint of five years earlier.

Even from the perspective of a career diplomat, all countries of South Asia and even beyond entrust Rajan with practically all diplomatic assignments these days. He has also set another record in replacing Professor Bimal Prasad, the last political appointee here.

This signified a shift from the modality adopted by India in the sense that only five of 15 predecessors of Rajan were career diplomats: Harishwar Dayal, who sadly died in Nepal; Maharaj Krishna Rasgotra; N.B. Menon; N.P. Jain; and A.R. Deo. But like our earlier choices as ambassadors to India and other countries, a trend that we have abandoned in favour of political amateurs, there were very few political people, as most of them were senior bureaucrats of proven merit and distinction.

Interestingly, only five career ambassadors, Narapratap Shumshere Thapa, Yadunath Khanal, Jharendra Narayan Singha, Jagdish Shumshere, and Bindeshwari Shah, have so far served as our ambassadors to Delhi, with political appointees monopolising the position in the post-1990 era.

Rajan, as the second Marathi-speaking ambassador after Bhalchandra Krishna Gokhale, relates his utter surprise that two-time Prime Minister Krishna Prasad Bhattarai could understand his conversation with his wife in the mother tongue.

To come to the core of the book, it has an introduction and three broad sections. The introductory chapter sets the book's tone with the opinion that India, as the bigger neighbour with its slogan "Neighbourhood First," should take the lead with a fresh beginning on its ties with Nepal, "adjusting diplomatic functioning, style, policies, and priorities." It also advocates an essential "ambience of mutual trust" and accommodation, imbuing Nepal as co-passengers on the journey towards speedy inclusive development."

Though intimately connected, all three sections are compact and independent units with separate conclusions. Again, the division of labour is such that the first section, with 77 pages entitled "Diplomatic Gleanings: A First-Person Account", is understandably written by K.V. Rajan.

This portion deals with monarchy, mainly under King Mahendra and Birendra, and various political experiments that have accompanied Nepal's tortuous course for systemic changes from time to time. He blames both Nepal's "failings" and India's "mismanagement" over the last seven decades for what he portrays as the status of resultant bilateral ties as "ever deepening and widening mistrust".

The second section is more political and is a compact statement of Nepal's political developments. Quite naturally, it is the largest unit of the book, comprising 117 pages. Jointly authored and aptly entitled "Transitions of the Himalayan Kind", it depicts pitfalls in Nepal's politics, governance, and consequent fallout on Nepal-India relations. Its coda is mixed.

It tends to hail Nepal's "extraordinary and full of surprises" democratic transition, highlighting the scale and extent of Nepal's roller-coaster drive towards democracy with the promulgation of seven constitutions in sixty-seven years, with none of the prime ministers completing their tenures.

The third and last section, the shortest with 62 pages and again a joint contribution, is most important because it is more prescriptive with the appropriate title, "Re-purposing India-Nepal Relations".

Succinctly analysing Nepal-India ties, the authors tend to portray Nepal's alternative development model and depict bottlenecks towards faster economic and social development in the interests of both countries. The section ends with a futuristic sub-chapter, Beyond Borders: Bilateral, Regional and Sub-Regional Cooperation.

In a nutshell, the book is a mixture of what is called in India 'Khatta and Mithha, an essential mix of everything, problems and prospects, utter failures and empty initiatives, and rampant political instability, irrespective of the change of Nepali governance, and widespread discontent and frustrations among Nepali people.

It vividly portrays the tortuous course of ties with constant upheavals, including India's economic embargoes and pressure tactics, and essentially a punitive action, possibly contributing to anti-Indianism in Nepal. It also shatters many claims on the part of our political actors about their supposed contributions.

We congratulate the authors for their initiatives. The moot point is whether they have been able to suggest concrete measures for resolutions or have just opened another Pandora's box of bilateral ties, which remains to be seen and adequately assessed by serious readers.

(Bhattarai is a former foreign secretary, ambassador, and author. kutniti@gmail.com.)