- Tuesday, 16 December 2025

A Succinct Portrayal Of Nepal

While the number of books on Nepal's social, political, or foreign policy context written in English, particularly by Nepali writers, is quite limited, Sanjay Upadhya, now based in the United States for many years, has attempted a comparatively short but substantively integrated work to depict Nepal covering quite a longer span of almost three centuries.

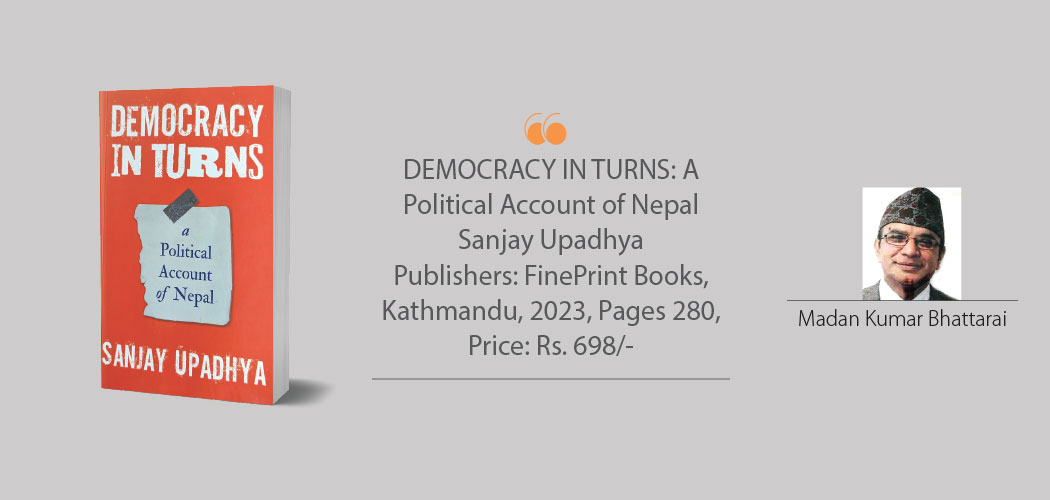

With a good flair in the language, Upadhya's book is entitled DEMOCRACY IN TURNS: A Political Account of Nepal, itself conveying the ups and downs that have marked the Nepali political landscape after the reunification of the country under the able leadership of King Prithvi Narayan Shah, the architect of modern Nepal. Interestingly, the major title of the work is borrowed from the last chapter of the highly readable book that tends to show semblance of concluding observations, though not expressly said so by the author.

Divided into eleven chapters with a short bibliography and quite comprehensive endnotes, the author confesses in his short preface that he has deliberately concentrated on the periods 1990-2002 and post-2006, with only short, if not sketchy, treatment of earlier periods, possibly to depict the matter in proper perspective. It is in this context that the first three chapters may be understood more as background notes.

The first chapter is 'Kings, Courtiers, and Convulsions,' which briefly takes the reader to a rather panoramic view of Nepal's politics and foreign relations, albeit quite limited during the period. This period ranges from Nepal's rise as a unified nation under Prithvi Narayan Shah to the end of the Rana regime in 1951, quite a long era of tumult, including fratricidal politics and violent changes of regimes, external intervention, and even two special missions to Europe under Prime Ministers Jang Bahadur and Chandra Shumsher, respectively.

The second chapter, 'Uneasy Cohabitation,' speaks of the 1951-1960 era that saw varying degrees of conflicts but essentially related to the sphere of politics. Conflicts pertained to Prime Minister Mohan Shumshere and political parties, particularly Nepali Congress, King Mahendra and political parties, persistently internecine conflict within the Nepali Congress, and, last but not least, tussle between King Mahendra and the first elected government that led to the ouster of the first popularly elected Prime Minister Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala from power within one and a half years of his assumption of authority.

The chapter also deals with Indian government's role in Nepali politics, always a controversial issue, and criticisms levelled against both Prime Ministers, Matrika Prasad Koirala and Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala, in respect of Koshi and Gandak Agreements with charges that they failed to take into account Nepal's vital interest in signing such deals.

Direct rule by two monarchs of different perceptions and approaches, King Mahendra and King Birendra, is portrayed in the third chapter, Palace-led Partylessness, trying to show that this was possibly the only time (1960-1990) when monarchy held sway in influence in a period of almost three centuries, except for a short period of two very short stints of such rules by King Gyanendra in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Three additional chapters, Democracy's Do-over. Leveraging legitimacy and consensus and compromises, deal with what can be called teething pains of democracy after the restoration of multiparty order that marked Nepali politics during 1990-2001. The Tanakpur Agreement and other issues with India also occupied much of the attention during this period.

Chapter seven, with the title Regicide Amidst Raging Rebellion, is self-explanatory in the sense that the assassination of the entire family of King Birendra and violent Maoist rebellion not only dented Nepal's image but also put a reverse gear in the country's socio-economic development.

Three subsequent chapters respectively deal with two short takeovers by King Gyanendra, the 12-Point Agreement, two Constituent Assembly elections, the declaration of the country as a federal republic, internal political fissures, and crises of constitutional governance that gripped Nepal in the post-2001 era.

The eleventh and last chapter's nomenclature shared by the title of the book, as already stated above, is an epilogue of sorts. Though brief, it is the most important part of the book, as it tends to dwell on a number of factors that have started to govern the Nepali political landscape for quite some time now.

These include conflicting versions on the role of monarchy, perpetual internal strife among political parties for partisan and individual interests rather than national interest, ideology versus personality, the divisive nature of our rule and corruption, assertive non-political actors, representational resentment and anguish of the electorate, multi-hued foreign hands, etc., that have characterised the Nepali psyche for quite some time.

After going through the book, admirably written in a free and smoothly flowing exercise, one can legitimately question some aspects not referred to in the book, especially by those who know the background of the author.

First, while dealing with the brutal assassination of Shri Teen Maharaj Ranoddip Singh in 1885, he should have at least mentioned the name of his great-great-grandfather Subba Chandra Kanta Aryal, who preferred to go into exile after completing the last rites of the murdered prime minister that he had served loyally, rather than seek favour from the new authority.

Second, in dealing with both the evolution of Nepali Congress particularly its student wing in India, his father Devendra Raj Upadhya who later served with acclaim in civil service and was Secretary for Industry and Commerce, had played quite a substantive role.

Third, the senior Upadhya was also a seasoned diplomat for a longer period of eight years, assuming such crucial assignments as Deputy Permanent Representative in New York and Head of Mission in Bangkok, and contributed a lot to Nepali diplomacy. He was also a prolific writer.

Possibly, Sanjay Upadhya, with extreme modesty, wanted to keep a low profile of both himself and his family. The only lacuna, if one may call it so, is the failure to mention the spate of administrative dismissals made by the Nepali government in 1992 that possibly led to irreparable damage to Nepali bureaucracy.

Otherwise, the book is a welcome addition to the literature on Nepal in English. The work is important for all those interested to know Nepal at a glance while at the same time providing some basic information to researchers and analysts. I congratulate Upadhya on his commendable initiative.

(Dr. Bhattarai is a former Foreign Secretary, ambassador and author. kutniti@gmail.com.)