- Thursday, 19 June 2025

The Story Of Bagmati

The River of gods and mortals alike,

A lifeline of the Kathmandu Valley

I cradled your civilisation

Nurtured your dreams,

And purified your souls

Sacred, worshipped, and revered,

A goddess flowing endlessly through your lives.

Do you remember me, Kathmandu?

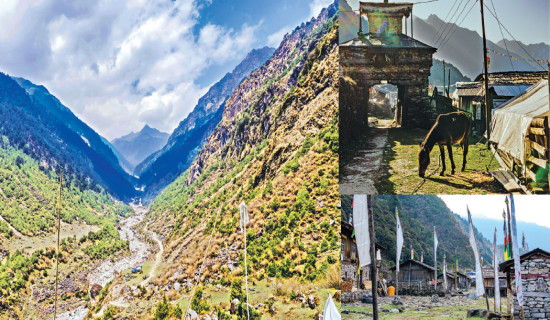

Long ago, when the sage Manjushree drained the great lake, I emerged weaving through your fertile lands. You built your temples, homes, and lives along my banks. The holy river, the one you offered your prayers to, the river that purifies your soul and connects you to the divine. Birth, to death, to eternity, your companion, always flowing through your side.

But now, as I flow through your valley, I am no longer the river you once admired, and it makes me wonder:

Do you still see me as sacred? Or have you forgotten me altogether??

Sacred and profane. How do you differentiate between the two when the line between them has always been so blurry? Holiness does not mean invincible, but it does mean extraordinary. To you, I was a goddess, eternal and invincible. You poured your faith into me, but alongside it came the filth. Marigolds you offer float on the surface of my waters, mingling with plastics, sewage, and toxins you pour onto me. I am left bare, with sand being taken out of my riverbed, choking on what little hope I had left to somehow save myself.

This contradiction, this coexistence of the sacred and the profane within me, is the great irony of my existence.

Impact of cities

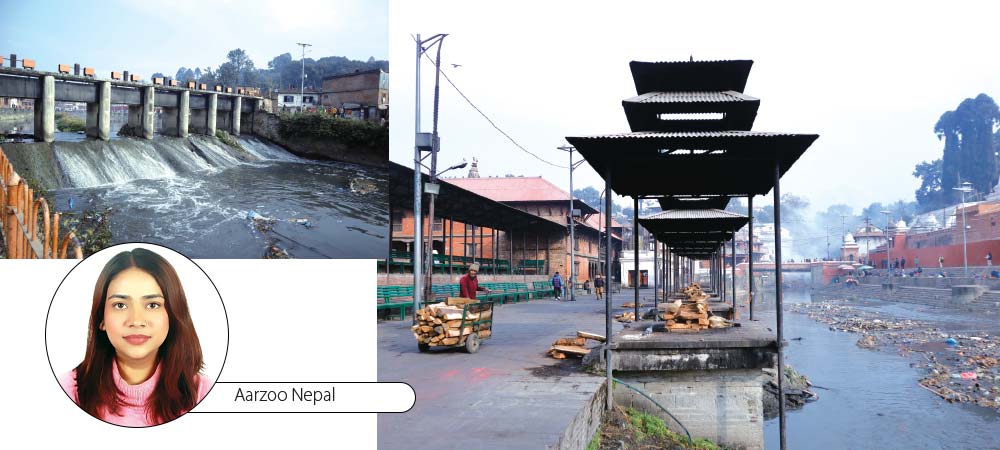

Once a symbol of purity and spirituality, the Bagmati River is suffering the severe consequences of rapid urbanisation and mass negligence. Originating from the Shivapuri Hills and making its way to the sacred grounds of Pashupatinath Temple, this river changes the form it is in within miles—an impact of unchecked and severe pollution.

The river, which was once considered a lifeline of the Kathmandu Valley, is now a health hazard, all thanks to the decades of industrialisation and urbanization. According to the High Powered Committee for Integrated Development of Bagmati Civilisation (HPCIDBC), an estimated 93 per cent of the wastewater entering the river comes from unfiltered and untreated domestic sewage, and the remaining 7 per cent of it comes from industries. Religious practices add another layer of irony to the already strained lifeline of Bagmati, with ritualistic offerings, cremation, and festivals adding more to this burden.

The Bagmati River Clean-Up Mega Campaign that started on May 19, 2009, provided a glimmer of hope. By 2023, the volunteers had removed over 20,000 metric tonnes of waste from the water. However, removing the surficial pollutants does not help with restoring a river damaged by toxins, chemicals, or faecal matter.

Initiatives like the Bagmati River Basic Improvement Project (BRBIP) and the Kathmandu Valley Wastewater Management Project (KVWMP) were started to improve water quality and restore the river. These projects included wastewater treatment plants, constructed wetlands, and the controversial Nagmati Dam, which was purposed to boost the flow of the river during the dry season. However, none of these projects could achieve something significant. According to the data provided by KVWMP, funds totalling $136.7 million from sources like the Asian Development Bank (ADB), OPEC Fund for International Development, and the Nepal Government have been allocated for the treatment of the Bagmati River, yet any substantial impact remains negligible. Comparing the water quality report published by HDCIDBC in December 2023 and December 2024, we can see that the pollution is getting worse. For example, turbidity—a measure of the degree to which the water loses its transparency due to the presence of suspended particulates—at Sundarighat increased from 132 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) to 201 NTU. Similarly, faecal coliform bacteria, or E. coli, in a water system that indicated fecal contamination rose from 54 x 10^3 Colony Forming Units (CFU) per 100 ml to 91 x 10^4 CFU/100 ml in Chobar. Although pH levels were stable, rising pollutants, phosphate levels, and faecal contamination point to serious pollution harming both public health as well as the environment.

Only 2.3 per cent of the wastewater is treated, with the remaining sewage flowing untreated into the river directly, even though we do have the infrastructure to treat wastewater, says Sudha Shrestha, NPO-WASH, UN-Habitat Nepal. She emphasises the need for stronger policies and coordinated strategies, including infrastructure development, regulations, and public awareness., as without effective policy enforcement and improvements in the infrastructure, the existing measures for the resurrection of the Bagmati River will continue to fall short. Similarly, she also emphasised the need for decentralised community-level wastewater treatment and better waste management practices, as currently, the outdated infrastructure is struggling to keep up with the rapid urbanisation seen in the valley. She points to successful international models like the Yamuna and Ganga Action Plans as potential solutions to restore the Bagmati River’s health.

Bagmati reflects Kathmandu and the state that it is currently in. A cautionary tale of what unplanned and unmanaged urbanisation can lead to. And preserving this holy river requires more than just faith in its sanctity.

Plea for renewal

Three dips, they say, will break you free.

A cruel twist of fate, for I am the one who bears the weight of your sins, hopes, faith, and your very existence.

I am holy. I am sacred. The purifier, as you call me. The eternal witness to the cycle of life and death.

They dip you into my waters, a final, desperate plea to break you free.

I cleanse your remains, carrying the filth of generations within me. Another cruel irony.

And as I do so, I think, "Maybe this final act will grant me reincarnation, as I break you free of one?"

(The author is a media professional.)