- Saturday, 14 February 2026

Young People And Demographic Dividend

Young people in Nepal make up a substantial portion of the population, with nearly 56 per cent of the country’s total population being under the age of 30 in 2021. This demographic is crucial to the nation’s development and social progress, as young people are often the catalysts for change, innovation, and social movements. Their energy, creativity, and adaptability drive economic growth, influence cultural fabric, and play an essential role in addressing societal challenges. This article focuses on the demographic trends of Nepal’s young population, particularly examining the shifts in age structure over recent decades and the broader implications of these changes reflected as a phenomenon of demographic dividend.

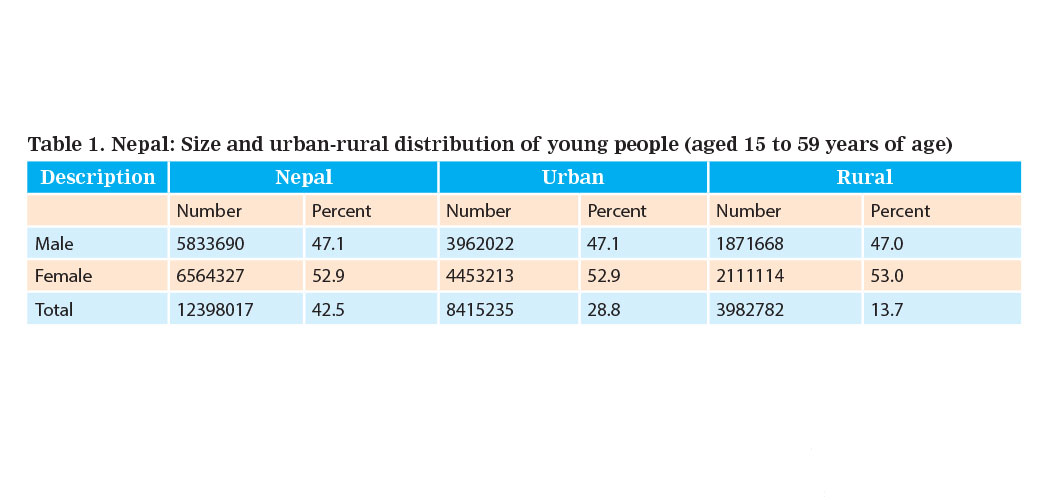

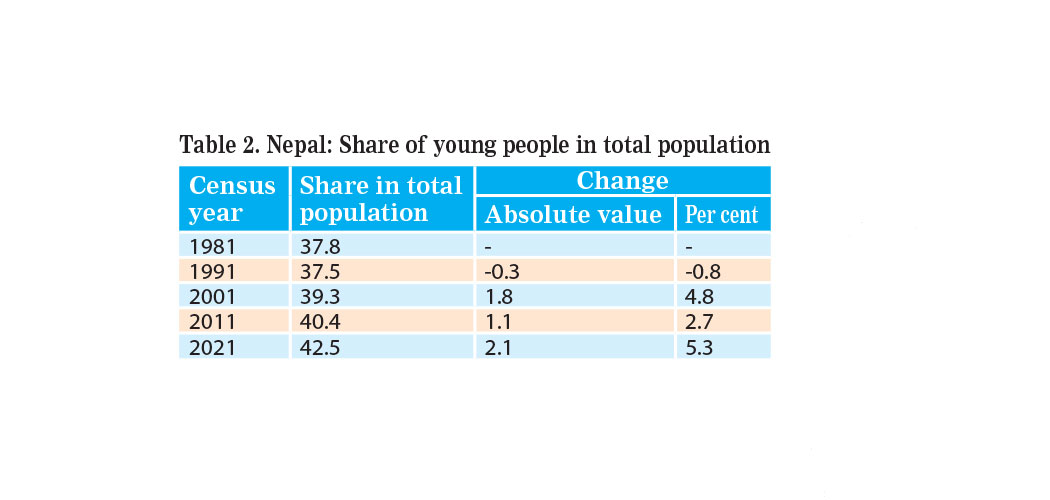

Nepal’s National Youth Policy 2072 (2015) defines young people as those aged between 16 and 40 years. At the time of the policy's formulation, this demographic represented 40.3 per cent of Nepal’s total population. The 2021 Census showed that the population in this age group had increased to 12,398,017, making up 42.5 per cent of the country’s total population, i.e., more than two out of every five people falling into this age category.

As such, they constitute a vital part of the workforce and serve as key drivers of innovation, economic growth, and technological progress. Globally, young people are considered powerful agents of social change and cultural transformation. As digital natives, young people are highly engaged with global issues and possess the ability to mobilise communities through social media and other digital platforms, further amplifying their influence and impact.

Demographic dynamics

As per the 2021 census, 12.4 million young people live in Nepal. Among them, 52.9 per cent are female and 47.1 per cent are male, resulting in a sex ratio of 88.9 males for every 100 females. Regarding urban-rural distribution, 67.9 per cent of young people reside in urban municipalities, while 32.1 per cent live in rural municipalities. This shows a higher concentration of young people in urban areas compared to the overall national population, where 66.2 per cent live in urban municipalities and 33.8 per cent in rural ones. The sex composition by urban and rural categories shows no significant difference when compared to the national average (Table 1).

Over the past 40 years, the proportion of young people in Nepal's total population has steadily increased.

The last five census results show a consistent rise in their share, with the exception of the 1991 (Table 2). Notably, this increase has been most pronounced between 2011 and 2021. This proportional growth occurred despite the overall national population growth rate dropping to 0.92 per cent per year between the 2011 and 2021 censuses. This suggests that the increase is primarily due to changes in the age structure, particularly in the children and early youth age groups.

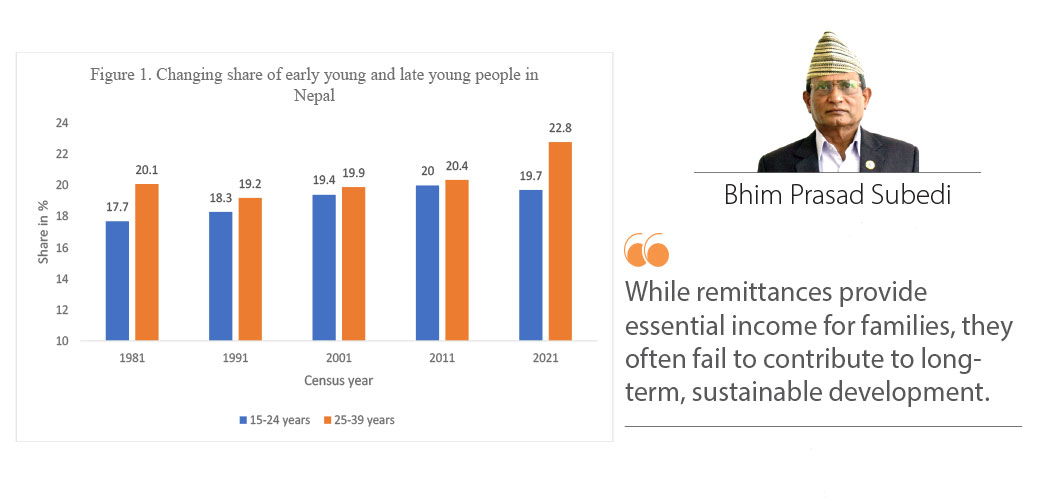

Young people can be broadly divided into two sub-groups based on the timing of key life events such as educational attainment, career development, and family establishment. The first group, often referred to as the "early young" population, includes individuals aged 15 to 24. This stage is primarily focused on education, with most individuals pursuing secondary and higher education. The second group, known as "late young" or "mature young," consists of those aged 25 to under 40. This group is typically engaged in career development, employment, and family formation. Both groups have seen changes in their share of the total population over the past five census periods, though the patterns of change differ between them.

Figure 1 shows the changing share of early and late young age groups in the total population over the past 40 years. Both groups have seen an overall increase in their share, with the early young group ranging from 17.7 per cent to 20 per cent and the late young group from 20.1 per cent to 22.8 per cent. However, the increases are irregular. The early young group grew steadily from 1981 to 2011, peaking at 20 per cent, before slightly declining to 19.7 per cent. In contrast, the late young group declined from 20.1 per cent in 1981 to 19.2 per cent in 1991, followed by a consistent increase. This shift indicates not only a growing proportion of young people in the population but also a shift from early to late young, which could lead to greater labour market stress and higher unemployment risk.

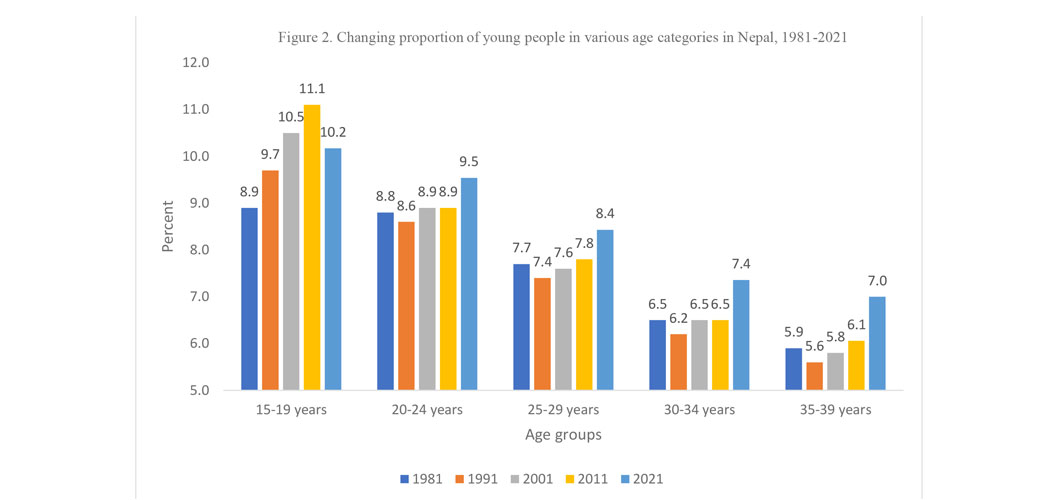

The shift in age structure, with the younger population moving toward late youth, becomes more apparent when the census data is disaggregated into five age intervals of five years each (Figure 2). The two extreme age groups—15-19 years and 35-39 years—demonstrate contrasting trends. The 15-19 age group shows a steady and relatively rapid increase until the 2011 census, rising from 8.9 per cent in 1981 to 11.1 per cent in 2011. However, by 2021, its share had declined to 10.2 per cent. Given the decline in the total fertility rate to just over 2 children and the significant drop in the proportion of children (under 15 years of age) to less than 28 per cent by the 2021 census, this decline seems to be a real trend rather than a random fluctuation. On the other hand, the 35-39 age group initially declined in 1991, but in the subsequent three censuses, it has shown a steady rise—from 5.8 per cent in 2001 to 6.1 per cent in 2011, and 7.0 per cent in 2021. This reflects not only the ageing of the younger population but also the broader trend of the entire population moving toward maturity.

Demographic dividend

The changes in age structure towards maturity and the distribution of the population across various age groups are often conceptualised as a demographic dividend. This phenomenon plays a crucial role in a country's socio-economic transformation and economic development. Essentially, it refers to a shift in the population's age structure, where the proportion of the working-age population (typically ages 15 to 59 or 64 years) is significantly larger than that of the non-working-age groups. From a practical perspective, it represents an economic growth opportunity created by the dominance of the working-age population.

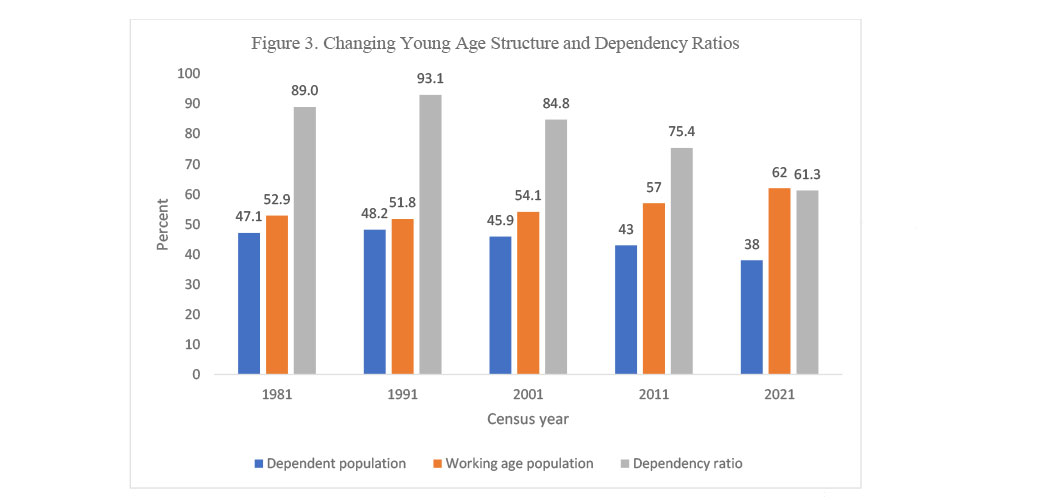

The demographic dividend became clearly evident with the results of the 2001 Census, which revealed a notable shift in the proportion of the working-age population. As shown in Figure 3, the changing proportions of dependent and working-age populations have significantly impacted the overall dependency ratio. Between 1981 and 2021, the proportion of dependents (both children and the elderly) decreased from 47.1 per cent to 37 per cent, a drop of 19.3 per cent. In contrast, the proportion of the working-age population increased from 52.9 per cent to 62 per cent, marking a rise of 17.2 per cent. This shift is reflected in the declining dependency ratio. Census data from the last five censuses indicate that the dependency ratio has fallen from 89 per cent in 1981 to 61.3 per cent in 2021, a decrease of 31.1 per cent. This means that the number of economically dependent individuals per 100 economically active individuals has decreased by nearly 28 per cent over the past 40 years, highlighting a significant and positive change in the country’s demographics.

The bright side of the demographic dividend in Nepal is that it presents a positive opportunity for overall socio-economic development, as an increased proportion of the population enters into the working-age group. As the dependency ratio decreases, fewer people rely on the economically productive population, and the larger workforce can steer productivity and contribute to economic development. Their larger presence generates higher demand for goods and services, boosting consumption and driving economic expansion. This demographic shift offers potential for higher savings, investment, and a greater focus on education and skill development, all of which can accelerate Nepal’s economic progress and improve living standards.

Harnessing the potential of the demographic dividend requires strategic investments in education, healthcare, and job creation. This demands a multisectoral approach and a supportive policy environment, which remains a challenge.

The large youth population requires more job opportunities, market-relevant education, healthcare, and skills training to drive economic and social productivity. Without these, the country faces high unemployment, migration, and social instability, often reflected in street protests and negative social media sentiments. The fact that 741,297 youths were approved for foreign employment in the fiscal year 2023/24, driven by limited domestic job opportunities, clearly shows a loss of skilled labour and hinders economic growth.

This large outflow of workers created a dependency on foreign economies, with remittances contributing to more than 25 per cent of GDP. Consequently, the country is caught in a cycle of relying on remittances rather than building a self-sustaining economy. While remittances provide essential income for families, they often fail to contribute to long-term, sustainable development. In the long run, without adequate planning and investment in key sectors and without sufficient employment opportunities that foster “hope” among Nepal’s youth, the economic potential of the demographic dividend risks becoming a burden.

(The author is professor of geography and former University Grants Commission chairman.)