- Friday, 26 December 2025

Shambala: Finding Inner Peace

Sita of Hindu Mythology Ramayana or Pema of the movie Shambala, it’s always women who have to prove the chastity. Why? Frustrated and depressed with the question, I came out of the cinema hall. Why is it always women who have to prove the fidelity? This started waves of questions about the status of women throughout human history, continuing till date. Comparable to what Sita had to face in ancient times, Pema has to go through the same fate in modern times. Despite being shot in the virgin Upper Dolpo, which kept my eyes stuck to the screen throughout the movie, unfolding the layers of the movie brought out the deeper and darker reality of the women even in the 21st century. The fear of “What will the society say” engulfed the personal feeling of Lord Rama then and still continues to affect feelings even in today’s world.

The movie is definitely a masterpiece that an artist can come up with only once in his lifetime, and Min Bahadur Bham along with his team might surely agree on this truth. Being the first Nepali and South Asian film in three decades to be selected in the Berlin Film Festival is a testimony to the truth. The wonderful panoramic shots filled with the details the plot requires continuously hook the attention of every audience when the story gradually unfolds its reality. The realistic enactment of the artists directed in convincing mode makes each one of the audience go through the emotions the characters go through. Since the main character is on the journey of self-discovery, the story flows in a slow-paced manner, which requires a lot of patience even for the audience, and so it’s obviously not an easy-digest movie like other commercial Nepali movies. The ultimate karma the lead character had to face and the life she later chose for herself shook the peaceful state of my mind.

Despite being true to her partner, Pema had to fall prey to the gossips of society, which her husband easily believes, and so turn away from her. Left and deserted, she embarks on her uphill journey for the search of the husband. Though she initiates the journey to prove her innocence, the journey turns out to be the journey of self-discovery, where she attains the ultimate knowledge of life. But yet, she falls prey to the patriarchal stereotype. Pema, an independent and strong enough girl, had to depend on the words of his male counterpart to maintain the prestige in the society. She is brought up as no less than a man by her parents, but all her other attributes become insignificant when her chastity is questioned.

Like Ram of Ramayan in Hindu mythology, Tashi of the movie also feared society more than the trust and love he had for his wife. As the fate of Sita in Ramayana who had a life of luxury before marriage but ultimately lived all of her life in grief and trouble just for the sake of having reverence in society. Despite accompanying her husband in all destitution, her husband made her go through Agniparikchya (test to go through fire to prove her purity), which still couldn’t satisfy her and so finally left her all alone in the forest to give birth and raise the kids in the hardship of jungle life. The tragedy is she is yet convicted as a sinner, which makes her give up her hope for life. This final fate of Sita had always troubled me, and so the fate of Pema in the movie raised the same feeling while watching the movie. Pema also tries her best to be a good wife by being kind and loyal to all three husbands she marries, as per the culture of the upper Himalayas. Just to make sure of her youngest husband having a good education, she has a good length of conversation with the school teacher. However, as the conversation takes place late in the evening in Pema’s house when Pema’s other husband was out for reasons. This makes society question her devolution.

Even her eldest husband, who is an educated priest, cannot accept the child, though he is portrayed as a person who stays aloof from all societal norms. He, in the movie, states, “Question about who is the father of the child doesn’t matter, but the process of the birth of the child is more important." The well educated person also doesn’t dare to give his name to the child. This clearly depicts that, though easy to state in words in an idealistic society, equal respect for women is still a far-fetched dream.

Determined to prove her innocence and purity, Pema moves on a journey in difficult, challenging terrain, hoping to regain her respect in society. Her struggles on the way don’t matter to anyone, but everyone solely focusses on her chastity, for which she silently revolts again and finally is destined to live single with the child.

My biggest fear was why women’s revolution throughout human history has always been a silent revolution. How long do women have to go through such deep-rooted patriarchal thoughts where a man can easily escape through any sorts of sin but women, despite being innocent, have to prove the innocence in all her steps? This raises a serious issue. Though modernity has made women capable as men, like the portrayal of Pema, who is shown as a woman who can do all the works of men and women both, women have to face the same fate as in traditional times. This proves that the utopia of equality between men and women is still a fanciful dream. Though Pema is strong enough and silently revolts against all the odds of society, she ultimately falls prey to the societal norms and has to go through the test of proving her innocence. This shows that the silent revolution of women will yield no progress.

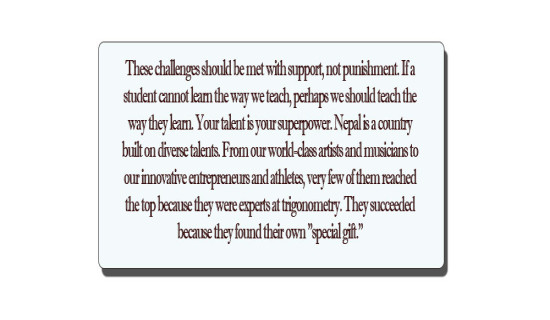

If women have to achieve the same status and prestige as men, women need to be vocal about all the revolution. Definitely, it’s true that the equal status we enjoy today in society is all because of the silent revolutions of the women of the past. But now, in modern times, the silent revolution is not going to bring the visible result. The need of today’s time is to be vocal about whatever we are fighting against. Dreaming of fortnightly change is foolish and unrealistic, but if we want the days of our daughters to be better than that of ours, then now it's high time for us to be vocal about all the revolutions we do every day. Feminism is not always about being vocal and advocating for the rights of women in seminars, but small steps we take at home or the workplace against the odds brought by the stereotypes. Or else, like Pema, who has always made her steps against the patriarchal norms in a silent manner but ultimately fell victim to the system by being forced to give the test, we will also have to be forced to the same fate. Pema finds solace and inner peace and ultimately happiness in the solitude, but being a social being, it cannot be a cup of tea for general women. So, if men and women have to live together, we need to bring the common ground of empathy where the men understand how women can feel rather than bringing in the men’s ego.

(The author is an officer at The National Archives.)