- Tuesday, 20 January 2026

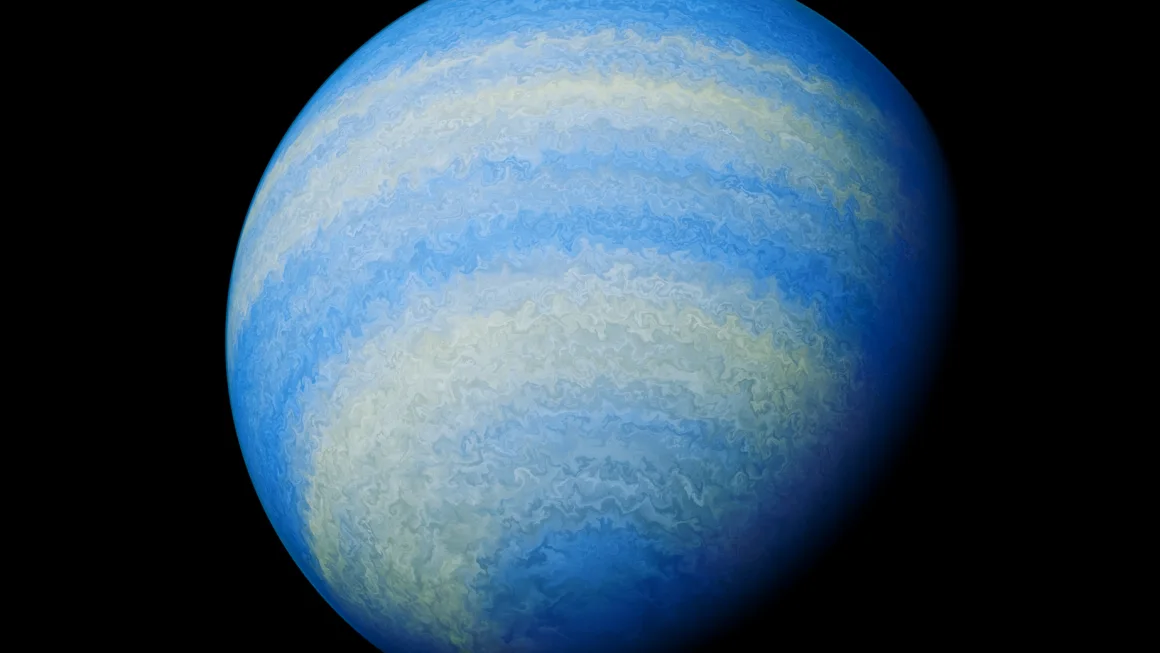

Scientists find a molecule outside solar system on planet with glass rain

By Ashley Strickland, July 9: An exoplanet the size of Jupiter has long intrigued astronomers because of its scorching temperatures, screaming winds and sideways rain made of glass. Now, data from the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed another intriguing feature of the planet known as HD 189733b: It smells like rotten eggs.

Researchers studying HD 189733b’s atmosphere used Webb’s observation to spot trace amounts of hydrogen sulfide — a colourless gas that releases a strong sulfuric stench and has never been spotted beyond our solar system. The discovery advances what’s known about the potential composition of exoplanets.

The findings, compiled by a multi-institution team, were published in the journal Nature.

An oddball planet with deadly weather

Scientists first discovered HD 189733b in 2005 and later identified the gas giant as a “hot Jupiter” — a planet that has a similar chemical composition to Jupiter, the biggest planet in our solar system, but with sizzling temperatures. Located only 64 light-years from Earth, HD 189733b is the nearest hot Jupiter that astronomers can study as the planet passes in front of its star. For that reason, it’s one of the most well-studied exoplanets.

“HD 189733 b is not only a gas giant planet, but also a ‘giant’ in the field of exoplanets because it is one of the first transiting exoplanets ever discovered,” said lead study author Guangwei Fu, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University, in an email. “It is the anchor point for many of our understanding of exoplanet atmospheric chemistry and physics.”

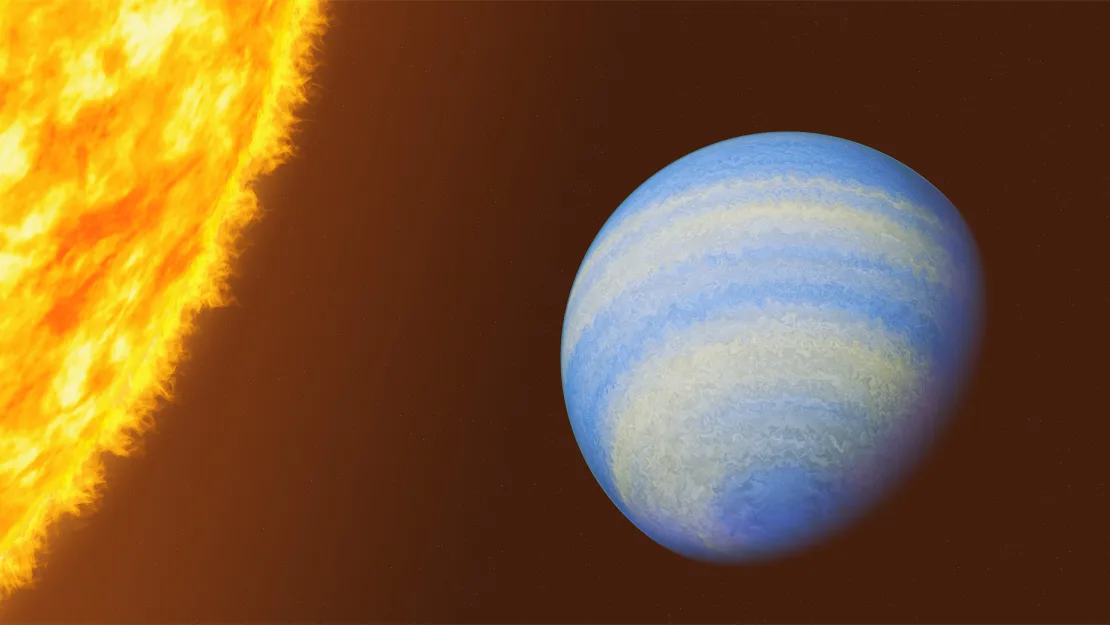

The exoplanet very closely orbits its host star, which causes the planet to have a scorching surface temperature. Roberto Molar Candanosa/Johns Hopkins University

The planet is about 10% larger than Jupiter, but much hotter because it is 13 times closer to its star than Mercury is to our sun. HD 189733b only takes about two Earth days to complete a single orbit around its star, Fu said.

That proximity to the star gives the planet a searing average temperature of 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (926 degrees Celsius) and strong winds that send glass-like silicate particles raining sideways from high clouds around the planet at 5,000 miles per hour (8,046 kilometres per hour).

A surprising stench

When astronomers decided to use the Webb telescope to study the planet to see what infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye, could reveal in HD 189733b’s atmosphere, they were in for a surprise.

Hydrogen sulfide is present on Jupiter and was predicted to exist on gas giant exoplanets, but evidence of the molecule had been elusive outside our solar system, Fu said.

“Hydrogen sulfide is one of the main reservoirs of sulfur within planetary atmospheres,” Fu said. “The high precision and infrared capability from (the Webb telescope) allow us to detect hydrogen sulfide for the first time on exoplanets, which opens a new spectral window into studying exoplanet atmospheric sulfur chemistry. This helps us to understand what exoplanets are made of and how they came to be.”

Additionally, the team spotted water, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide in the planet’s atmosphere, Fu said — which means these molecules could be common in other gas giant exoplanets.

While astronomers don’t expect life to exist on HD 189733b because of its scorching temperatures, detecting a building block like sulfur on an exoplanet sheds light on planet formation, Fu said.

“Sulfur is a vital element for building more complex molecules, and — like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphate — scientists need to study it more to fully understand how planets are made and what they’re made of,” Fu said.

Molecules with distinct smells, like ammonia, have been previously detected within other exoplanet atmospheres.

But Webb’s capabilities enable scientists to identify specific chemicals within atmospheres around exoplanets in greater detail than before.

Planetary heavy metals

In our solar system, ice giants like Neptune and Uranus, though less massive overall, contain more metals than the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, which are the largest planets, suggesting there could be a correlation between metal content and mass.

Astronomers believe that more ice, rock and metals — rather than gases like hydrogen and helium — were involved in the formation of Neptune and Uranus.

Webb’s data also showed levels of heavy metals on HD 189733b that are similar to those found on Jupiter.

“Now we have this new measurement to show that indeed the metal concentrations (the planet) has provided a very important anchor point to this study of how a planet’s composition varies with its mass and radius,” Fu said. “The findings support our understanding of how planets form through creating more solid material after initial core formation and then are naturally enhanced with heavy metals.”

Now, the team will search for sulfur signatures on other exoplanets and determine whether high concentrations of the compound influence how closely some planets form in relation to their host stars.

“HD 189733b is a benchmark planet, but it represents just a single data point,” Fu said. “Just as individual humans exhibit unique characteristics, our collective behaviours follow clear trends and patterns. With more datasets from Webb to come, we aim to understand how planets form and if our solar system is unique in the galaxy.”