- Monday, 23 February 2026

Eurasian Lynx Conservation Challenges

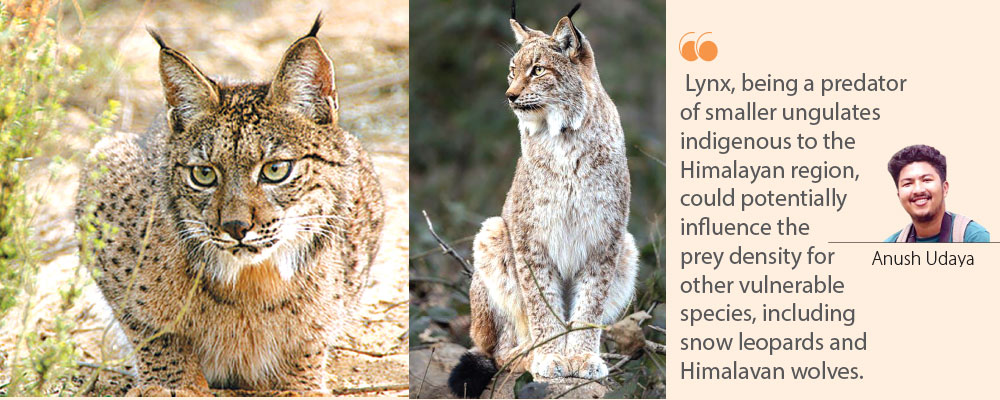

The Eurasian lynx represents one of the twelve wildcat species found in Nepal. Named after the Greek word ‘lynx’ which means to shine, its home range extends across Europe to Central Asia and some parts of South Asia, such as the Tibetan plateau and Himalayan regions. Lynx, a medium-sized feline species, is mostly solitary and nocturnal, with peak activity at dusk and dawn. Its distinctive features include black-tufted ears and a short tail with black spotted fur, along with thick silver fur in winter. Each lynx possesses a distinct coat pattern, except for a few individuals that lack spots. This distinctive pattern assists researchers and scientists in identifying individual lynxes. Male lynxes are, on average, larger than female lynxes.

Globally, recognised as a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Red List and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the population of Eurasian lynx in the wild (Lynx lynx) is estimated to be around 50,000. Lynx is a seasonal breeding species, with mating occurring in February and March. The gestation period lasts from 67 to 74 days, resulting in most kittens being born in May or early June. Kittens typically remain in their mother's territory for a while, but eventually, they must disperse and locate an unoccupied territory with sufficient prey density.

Males usually disperse farther than females, who often establish home ranges that partially overlap with their mother's territory.

There are four species of lynx found throughout the world, namely the Eurasian lynx, the Iberian lynx, the Canada lynx, and the Bobcats. The largest of the lynx species, the Eurasian lynx, preys on smaller ungulate species such as roe deer, chamois, and musk deer. The Eurasian lynx is also known to prey on pikas, large rodents, and hares.

The Eurasian lynx has been designated as a vulnerable species by the National Red List of Mammals of Nepal. It was initially documented in the Mustang District and is known to inhabit the elevated Himalayan regions of Nepal, including Manang, Mustang, and Humla districts. The study of scats of the Eurasian lynx collected from the Dolpa region found that its diet mostly consisted of woolly hare, Himalayan pika, Himalayan marmot, and a few traces of domesticated goats too.

Threats

The increasing urbanisation and loss of potential habitats for lynx have been a threatening concern. The deforestation of forest lands, forest fires, unmanaged urbanisation, and degradation of pasture lands contribute to decreasing lynx populations around the world. Poaching and road kills have emerged as significant threats to these felines. The study done on survival rate and causes of mortality in Eurasian lynx in multiple landscapes confirmed that mortality rates increased from 2 per cent to 17 per cent due to hunting and poaching.

An important challenge to lynx conservation efforts is the scarcity of comprehensive data. Their elusive behaviour makes them a particularly difficult species for research and data collection. High-altitude research requires a large sum of money and takes a long time. In country like ours, high-altitude research predominantly targets mammals such as snow leopards, Tibetan brown bears, and Himalayan wolves. Consequently, data concerning lynx populations remains limited. Furthermore, the escalating effects of climate change disrupt lynx habitats, potentially leading to migration patterns, hormonal imbalances, and declines in prey availability. The combined effects of increasing competition and decreasing prey density pose a significant threat to lynx conservation efforts.

The Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe (LCIE) has conducted a region-wide conservation programme to preserve the population of lynx species in the wild. The major focus of the initiative was on rebuilding the population of the lynx species through the regeneration of forests, legal protection, and policies, along with increasing the prey density. According to this initiative, there is no record of man-eating lynx until now, but few incidents of injuries caused by lynx have been recorded in Europe, where most of the attacking lynx were wounded, captured, or rabid.

The study done about the recovery of the Eurasian lynx in Europe praises the optimistic public attitudes and wildlife management policies (both national and international legislation) that saved the species from extinction during the mid-20th century. The local people acting as principal stakeholders removed the concept of bounty hunting and banned the use of poisons for killing. Also, better management of wild ungulates and efficient post-war forestry practices led to a dramatic increase in prey base, along with woodland management and conservation.

Conservation efforts within the Himalayan region primarily concentrate on the snow leopard, resulting in a scarcity of comprehensive information and scientific research concerning the Eurasian lynx. The documentation of live sightings and camera-trap observations of this feline species in the country has been minimal.

The available knowledge about the species is primarily derived from faecal DNA sampling and camera trap images.

The overview of Eurasian lynx monitoring and conservation in Europe suggests several field methods and analytical tools to provide assistance in studying the lynx population. Oppurtunistic data collection, camera trapping, snow tracking, hair trapping, systematic questionnaire surveys, mortality recordings, telemetry, etc. are the major techniques used in Europe for monitoring the Lynx population. In most European regions, scientists and researchers prefer to use camera trapping with capture-recapture analysis for robust estimates of lynx abundance. Also, the creation of consultative groups including locals and citizen scientists is playing an essential role in lynx conservation.

The study and research of lynx are of paramount importance in preserving the ecological balance and biodiversity in the Himalayan regions of Nepal. Lynx, being a predator of smaller ungulates indigenous to the Himalayan region, could potentially influence the prey density for other vulnerable species, including snow leopards and Himalayan wolves. Furthermore, lynx may also be a contributing factor to livestock depredation, which in turn can escalate human-wildlife conflicts within the Himalayan region.

(The author is pursuing higher education at the Institute of Forestry, Pokhara Campus.)

-original-thumb.jpg)