- Wednesday, 24 December 2025

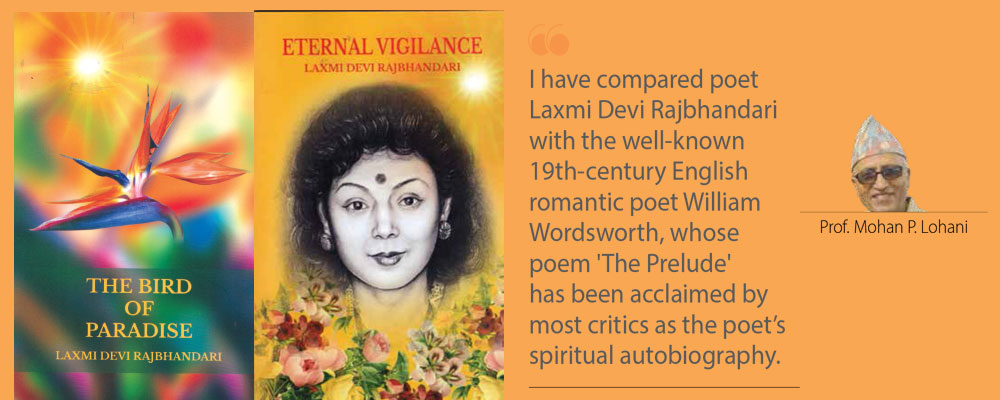

Spiritual Poet With Fervent Vision

Poet Laxmi Devi Rajbhandari is a familiar name in Nepali poetry. She has initiated a new trend by making spiritual truth and reality the dominant themes in her poetry. It is different from poetry, which is based on didacticism. The message that she conveys through her spiritual poems has deeper significance and calls for understanding and appreciation at a higher level of consciousness. What is spiritual reality? She describes it as ‘the inner glow aflame’. The acquisition of academic knowledge is not her goal. She affirms that divine grace transcends bookish knowledge. She would prefer to be left alone and lost in nature, away from concrete structures that symbolise material civilisation.

The poet considers herself a ‘lone traveller’ in the spiritual journey of life and is prepared to ‘withstand all deceits, disrepute, and despises’ to which she was subjected in the past. She was a misfit in the mundane world. Now she is faithful to her own being. The poet who compares herself to the briar rose had to undergo unimaginable misery and suffering before she realised herself. Attempts were made to crush her spirit, but they failed. Nowhere did she find peace and tranquillity except when she was with myself within the cave of my inner being’ (Eternal Vigilance).

The poetic persona in all 3 anthologies that were launched on 2081/1/14 with excellent comments by 3 learned speakers is preoccupied with the spiritual world, which stands for ‘inner light, self-realisation, and illumination’. The Bird of Paradise, one of the three anthologies with a preface by me, impressed me most with the poet’s ability to forcefully and with unwavering conviction communicate her perception of the inherent dichotomy between matter and the spirit (the body that perishes and the imperishable soul). The dichotomy is resolved when the poetic soul becomes the bird of paradise on a spiritual flight. It is the poet’s strong conviction that it is possible to perceive divine presence in an intuitive flash. In other words, the ultimate truth can only be perceived intuitively, not intellectually. Reasoning or a rational approach can’t solve the enigma of spiritual truth or bliss. In all her spiritual poems, we come across recurring expressions like the vast ocean, the vast expanse, and the vast jungle to demonstrate or reveal the contrast between the ‘radiant effulgence’ epitomising divine grace and profound darkness, or pitch dark, which symbolises the ignorance of the ego-self. The poet who does not crave worldly fame and name wants to be a liberated soul without ego. The price of such liberation, or emancipation, is eternal vigilance. Impressed by God’s eternal surveillance, the poet considers herself only ‘a spark in your unceasing circuit of cosmic energy’. God is a ‘continuum’ or a’ continuous rhythm: the poet elaborates: ‘I am but finely attuned to your soulful flute; my heart flows out spontaneously to the celestial melody’. These lines are noted for their poetic elegance and are aesthetically appealing. There are multiple lines like this in all her poems.

I have compared poet Laxmi Devi Rajbhandari with the well-known 19th-century English romantic poet William Wordsworth, whose poem 'The Prelude' has been acclaimed by most critics as the poet’s spiritual autobiography. It is described as the most admirable record of a soul’s progression towards full possession of itself. Just as nature to Wordsworth was more than an external phenomenon, the manifestation of divine being, Rajbhandari too calls herself the ‘daughter of nature’ and a ‘child of brooks and creeks’, ‘rocks and pebbles’ that are the source of her spiritual bliss. A solitary briar rose, the poet loses her identity in the crowd and finds solace in solitude, or ‘the natural nature’.

As she finds solace amidst the ‘natural nature’, she can hear the un-strummed divine symphony even in the dark, pitch-black pitch-black. The rhythmic melody of the ‘throbbing water’ exhilarates her and uplifts the spirit. She is alert to the rustling of the leaves and the chirping of the birds. Her love abounds in the glimmer of the stars, in the mellowness of the moon, in the affluence of the sun, and in the vibrancy of nature. She goes a little further and says that the divine being can speak ‘through the gurgling stream, the blowing winds, the thunder in the sky, and in silent or unspoken words’. It is in the silence or beauty of nature that the presence of a divine being is deeply and ultimately felt. The death of her husband, Dr. Purushottam Rajbhandari, the first ENT specialist in Nepal, in March 2018, led the poet to pour out her grief in these words: Now spirituality has been a strong pillar for me to hold. She further adds: My husband’s pure spirit is still with me; my soul, which is infinite, guides me through.

I would like to conclude this paper by quoting the following stanza, which brings out the poet’s spiritual vision and fervour:

When the body is a wick

The mind is the oil

burns into a flame in God’s name

All is burnt

what remains?

The complete soul

the ember, a nonentity

an eternity.

(The Bird of Paradise)

The use of the wick and oil metaphor is so appropriate in the above stanza to convey her absolute faith in the ‘complete soul’. Rajbhandari feels rejuvenated in this state of existence where a soul lives spiritually. In other words, her goal is to reach the pinnacle of peace, sublime bliss, and tranquillity.

(The author is a former head of the Central Department of English at TU.)